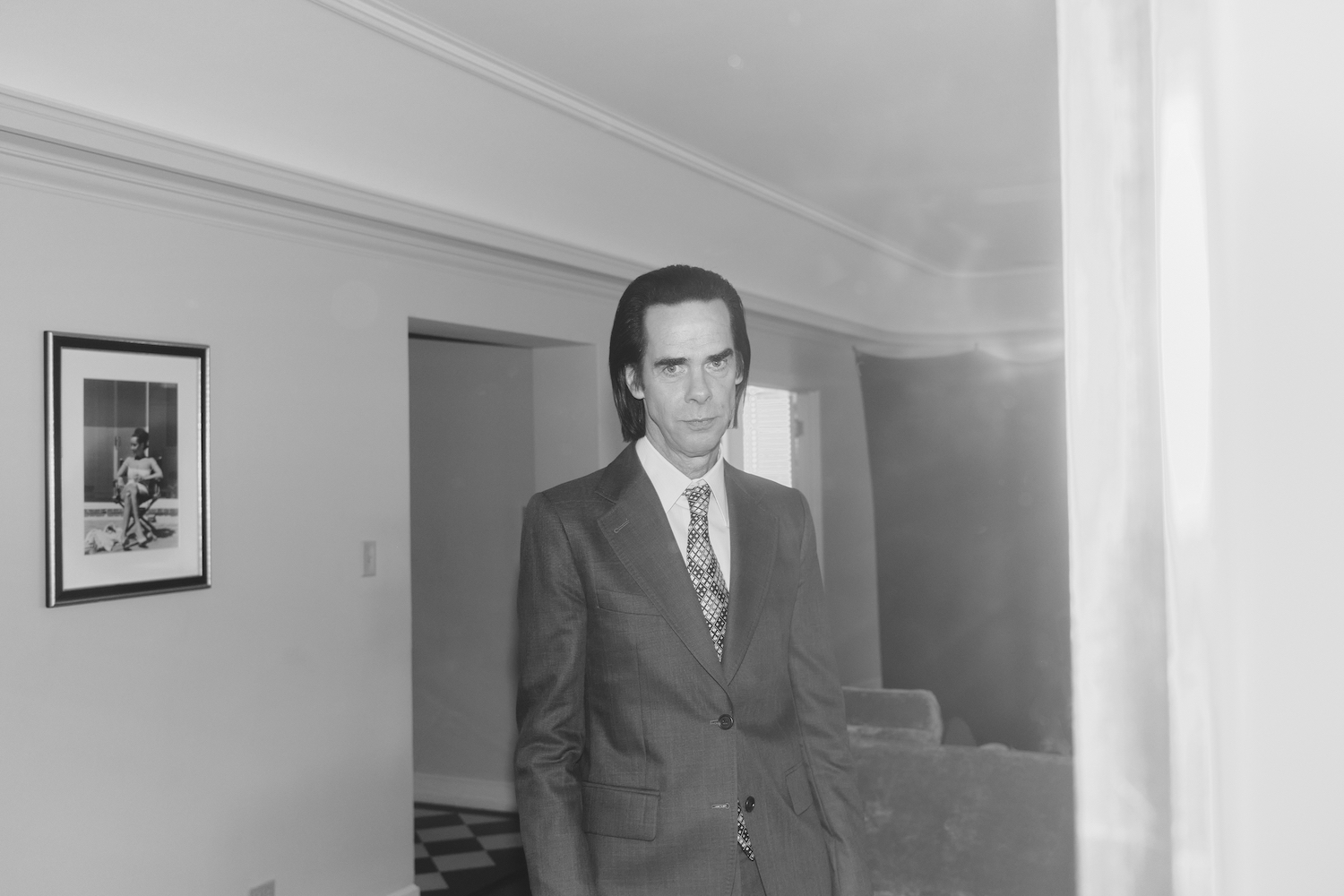

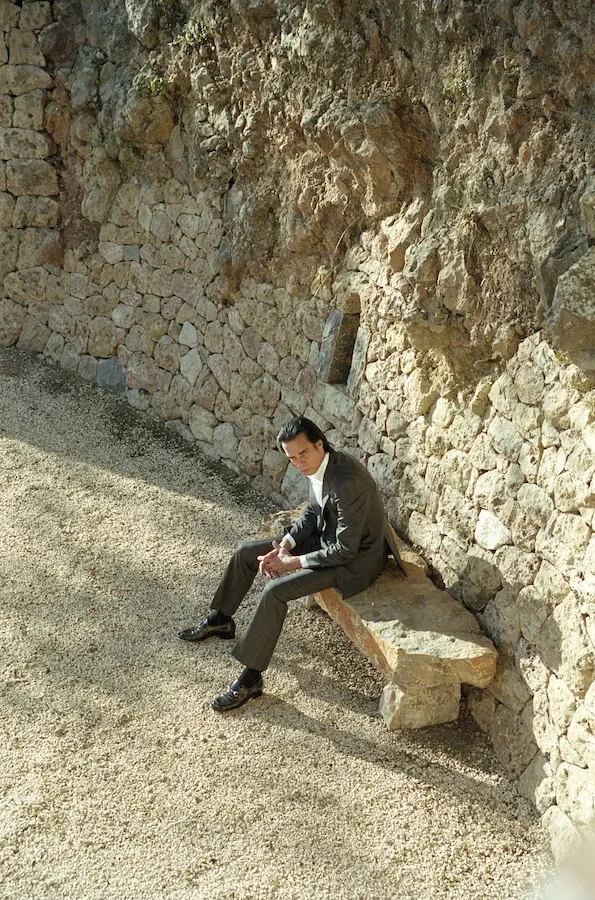

Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds have been a band since 1983 and have gained a cult following around Nick Cave’s persona as a sort of Prince of Darkness. But about ten years ago, he encountered real tragedy that changed him and his music completely: Cave’s 15-year-old son, Arthur, fell off of a cliff and passed away. The past two Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds albums dealt with that trauma. The band faded into the background, barely present on Skeleton Tree and Ghosteen. Cave worked his grief out in public. He did a Q&A tour where fans asked him difficult questions about dealing with grief. Cave also started The Red Hand Files, an ask-me-anything style blog where fans write, “Are songs from God?” and “I’m wondering if you have any thoughts about loneliness” and Cave answers them thoughtfully and beautifully. Out of this carnage, Cave seems to have turned a leaf. The “People Ain’t No Good” singer has espoused an empathy that wasn’t present before, and this new album, Wild God, catches Cave with a new outlook and perspective on life. Wild God is The Bad Seed’s 18th studio album. It deals with Cave’s journey through grief of the past decade and landing on new, long-dormant emotions like joy that the band are experiencing once again. WNXP was granted this rare interview with Nick Cave.

Justin Barney: What are the events in your life that have occurred between the last album that inform Wild God?

Nick Cave: I often think it’s a mistake to listen to a record and somehow feel that that record characterizes the sort of situation the person is in the world at that particular time. When I look back at my former records, I can’t really tell by listening to the records what was going on in my life. However, I think the last 3 or 4 records are signposts of a changing set of events and a repositioning of myself in the world due to the death of my son.

I mean, that’s the truth of it. That’s simply what’s going on with those records from Skeleton Tree, right through to Wild God. People are talking about Wild God as a new beginning, but I don’t see that. I just see that as part of an unfolding story that follows a devastation or a traumatic event.

The beautiful thing about it for me and, in a way, I’m sort of the last person to know what these records are actually saying, is that when I did play it back, you know, got the masters, we mastered the record, and, and I listened to that in a cursory way. “Yeah, that all sounds fine,” but I listened to the record a couple of weeks later, which is normally a pretty bracing thing to listen to your record, because all you can hear is the things you should have done, you can’t really love it, first you have to sort of hate it. Then you kind of grow to love it.

And this record, Wild God, I just sat and listened with this big smile on my face because it really felt like it was made by someone, in fact, a group of people who were just in a really good space. That life was okay. Life was full of joy, and laughter and playfulness and these sorts of things. You can hear the joy of creation in the whole thing.

Justin Barney: I listened to Wild God a couple of times, and I got to “Joy” and felt like a thesis for the album.

Nick Cave: It has that line in it: “The time for suffering is over, now is the time for joy.” Yeah. That’s actually one of the only songs on the record where I’ve actually written a bunch of lyrics and stuck to them. Normally, I’m just grabbing stuff from everywhere. Basically the first verse of of “Joy” is taken from a female blues singer from the 20s or something. It starts, “I woke up this morning with the blues all around my head. I woke up this morning, thought someone in my family was dead.” I heard that and I just thought, “Fuck.” That’s so sort of raw and weird, and so I wrote that down and then just started to collect lines. After that that went to this vision and the little boy. So, it starts off as a sort of piece of low Black blues, but ends up into some kind of high, Anglican, white, kind of we-stand-before-the-stars and the horns are playing and you feel like you need to stand up and salute or something. Salute the cosmos or something like that.

For me, there’s something… I’m just winging this now… There’s something male about this record. Whereas Ghosteen felt female in its way. By which I mean Ghosteen felt watery and fluid and without boundaries or something like that. Wild God is much more locked into something. It’s much more earthbound. It’s more masculine. I don’t know how to describe that in any other way. I know I’m sort of stepping into potentially hot water here, but there’s something sort of triumphant, old-school and there’s a beautiful use of the french horn, which is this sort of male instrument. It’s sort of a stirring, patriotic kind of sound. It has a stirring feel about things.

JB: What do you think accounts for that on this record?

NC: You know, I think that it was a bunch of men back in the studio. The Bad Seeds essentially hadn’t played anything on the last three records of any real substance. Or at least within the actual basic foundations of the songs. They sort of were a decorative element, if anything. Skeleton Tree was just too despairing for them to find any room to play on. When we brought them into the studio, my son had just died. It was just too dark and no one knew what to do with that record. And Ghosteen was so feminine and fluid and, that it was sort of too vulnerable to support the weight of The Bad Seeds. So they’d been out to pasture for some time. So this record was a bunch of men of their chains, dying to make a record and dying to make have a significant impact on the actual foundation of the music. It’s got that kind of feral energy to it.

JB: “Conversion” has a wild energy to it. How did you capture that preacher the middle of a choir sound?

NC: We had a gospel choir singing that, and they did all this “touched by the spirit” singing and all this sort of stuff, and I didn’t quite like the way that that was working in the sense that it sounded like a gospel choir stuck onto a kind of rock record, which is not a sound I particularly like, to be honest. Warren went to me and said, “Go in there and fuck ’em up.” So I sort of went into the studio and just sort of started screaming stuff out at them. These people are just extraordinarily talented at this sort of stuff, the call and response thing on a dime. Right? You don’t rehearse this stuff. So it was a whole kind of ad libbed thing that was just thrown on the top of this more structured gospel thrust. That made that so sort of chaotic and ecstatic. It was amazing.

JB: So that’s captured in the moment?

NC: Yeah, most of the stuff on this record. In fact, most stuff on the last four records is just improv.

JB: You talked about that in the book. You talked about going into the Ghosteen sessions with Warren and improvising.

NC: We’ve become spookily good at understanding each other. Or even when we don’t understand each other, some of our best stuff is this sort of collision of different intents. You know, I think the song is this, and he thinks the song is this, and he’s playing whatever, and I don’t really understand what he’s playing and he doesn’t really understand what I’m singing. And so you just get this weird kind of… I mean, “Joy” is a little bit like that. In “Joy,” Warren’s playing a circular, chordal structure, which I think is something else when I’m singing it and I can never quite land the end on where I think he’s starting. I think he’s playing in a different time signature, so it’s this giant accident. That’s part of the beautiful discomfort that runs through a lot of what we do.

JB: The song “O Wow O Wow (How Wonderful She Is)” is so different in it’s production. The vocoder is in there and it’s more playful. Who is that song about?

NC: That song is about Anita Lane.

JB: That’s what I thought.

NC: Yeah. Anita Lane was one of the original members of the Bad Seeds when the music scene in Melbourne was starting to emerge. When we young guys were sort of coming out of art schools and off the streets and so forth, and starting to make bands. We were this sort of dark, drug addicted force, that circled around this girl, Anita Lane, who sort of emerged at the same time, who we all were in love with. She was just this gorgeous, laughing, light, bright, flaming force that had enormous influence over us all. And we were boyfriend and girlfriend for years. And then she made some lovely records of her own with Mick Harvey, but eventually became more and more reclusive.

I just taped a little bit of conversation on a phone call we were having. I would ring pretty regularly over the years and I just caught this little bit. Then I remembered I had this little bit of of her speaking, from a phone call, about how we used to write songs together. She’s sort of trapped in a little remembering loop. When she’s talking about that, her life had changed terribly. She was sort of locked in a house on her own, more or less. She’s remembering what it used to be like. It was incredibly affecting to put that on the end of that song.

JB: The last song on the album ends with this choir. And Ghosteen ended saying, “I’m waiting for my peace to come.” Do you feel that it has come?

NC: It would be wrong to say my life is peaceful. I don’t know. But I do have a very strong understanding of the nature of the world. I think I understand the world. I think I understand what human beings are like. I understand that human beings have true value. I understand the true problem within the world is a kind of demoralized, cynical view of of the world that we are fed continuously by the media and online. This idea that the world is of no true value and that human beings are only destructive forces. And I know that not to be true.

I feel deeply attached to the world and in awe of its beauty. I walk outside and look at the world, and I think it can’t help but be a beautiful place. Deeply troubled, deeply broken, deeply unjust, yet, extraordinarily beautiful. That’s that’s a helpful thing to know.

JB: I think that people have put on this idea that, maybe, for a while you represented the opposite of that feeling. Did you not believe that at one point?

NC: I mean, look, I think I was like most young people. The default setting was the world sucked, you know, and people sucked, and the systems that we create in society and all the rest. It all sucked.

Now this is a position that I understand very well, but it’s also an extraordinarily indulgent position. It’s a position held, I think, by people who largely are half-formed human beings, by which I mean that they’ve yet to be truly broken by something. They’ve yet to truly suffer.

They may be looking at the world and seeing all the suffering and railing against the suffering of the world. I totally understand that, but I don’t think they themselves have truly suffered. Once that happens to you, and it will, I mean, I’m not saying that there aren’t young people out there that terrible things have happened to. But in general, these things will eventually happen to you. And it changes the way you see the world. You can’t afford to look at the world in that way. Or if you can, you are truly destroyed. For people who suffer intense grief, there are those that can’t exist without wrapping themselves around the absence of the person that is no longer there. This is an extremely problematic, dangerous thing to do.

I think that for most of us, the trauma happens, and ultimately we’re able to turn around and look at the world and see it… See that we are part of a common river of suffering. I don’t mean that in a gloomy way. We’re just part of the brokenness of the world. We recognize ourselves in each other. And, therein lies the beauty of things. That we are vulnerable, precarious creatures. That’s a very beautiful thing.

JB: Has your relationship with God helped you in that?

NC: Well, my my relationship with God is pretty… You know… I would call myself a religious person. I call myself a religious person because I do religious things. But I’m not a Christian. I don’t call myself a Christian. Or that I’ve converted to something. I would say that I am in the process of conversion, or have been most of my life, but far from being converted. So I’m full of doubts and uncertainty about these matters, and my religiousness is sort of based on on the smallest intuitions and softly spoken whispered.

JB: What do you think is stopping you from full conversion?

NC: Because it feels like a kind of an arrival of some sort that is sort of fully paid up. To be a fully paid up Christian, it just doesn’t feel like a creative or active place to me. There is a place adjacent to that, just between unbelief and belief that feels extremely vibrant. To be uncertain about things is, by its nature, bursting with potential. To be certain, one way or the other, you know, is to shut down the kind of cosmic conversation.

JB: As a Nick Cave fan I always look forward to the next album. I want to see what it brings. How do you continue to move forward?

NC: Well, there is a certain type of fan that is like that, right? There’s a couple of types of fans. Some are along for the ride. They enjoy the fact that you don’t know what the next record is really going to be about. You sit down and you listen to it and so very often, the sort of the record that you’re listening to is sort of, disowning or murdering the last record. The one that’s taken something of you to actually like. And then we made another one, and you have to start the process all over again. The work of trying to work out if you’re actually still in Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds fan. I like the records do that.

A lot of people go, “No, this is a step too far. I don’t like it. I’m out.” Other people love the adventure of it. And some people just wish that I’d get Mick Harvey back and Blixa Bargeld back and go back to making records like we used to make. But those days are over.

JB: Why do you think that people are still sticking and loving the new ones?

NC: I think it’s because the records keep changing. We’re not bound to anything. We’re smart enough to understand that if you don’t change and you don’t create new things and you don’t move in different directions, you grow stagnant and boring.

The person that’s really influenced me in that respect is Bob Dylan. You could say that his career is a series of brilliant disappointments. In that you get a new Bob Dylan record and you’re like, “Oh, God.” You really have to reassess your relationship with this artist. And most of the time you work out a way to love these records, and these records become extraordinarily meaningful to you because they require something of you. You don’t just sit back like a vegetable and the music wash over you. They require some imaginative interaction between the listener and the records. These brilliant things. And sometimes it doesn’t work. Sometimes you can’t get there. And this is okay too.

JB: That is very much how how I have felt as a Nick Cave fan, you know? All right, that’s it.

NC: All right. Man, lovely to talk to you.

JB: Thank you very much.

NC: Pleasure.