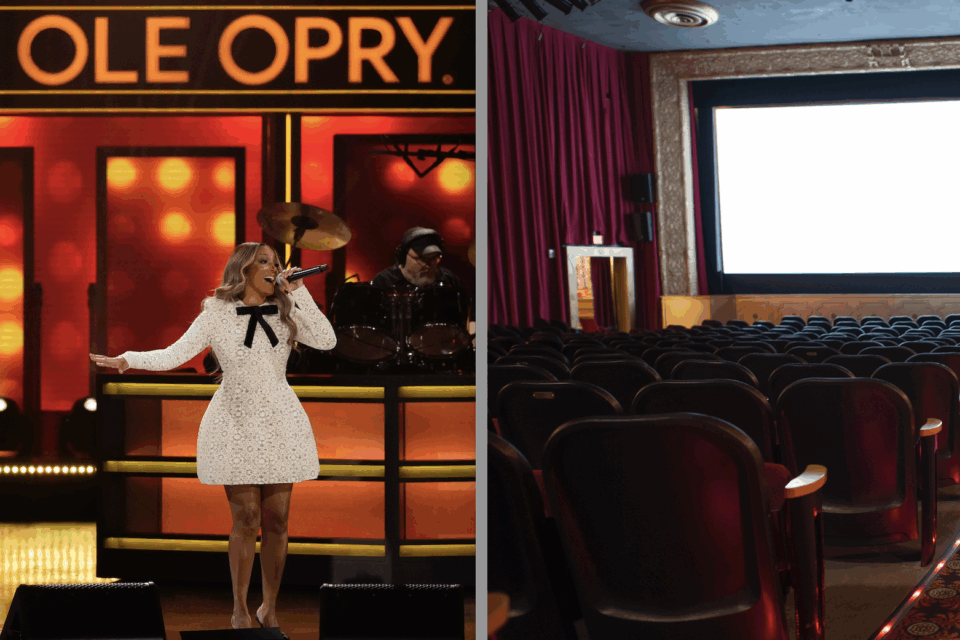

Jewly Hight: It really is not often that we get to see a cultural institution reach the centennial mark. And I think it’s even rarer that we have a year like this, when there are two cultural institutions in Nashville that have both reached their centennial, the Grand Ole Opry and the Belcourt Theatre.

Justin Barney: And their histories and their paths have intertwined in ways that we know and ways that we are about to find out.

There was a time where the Grand Ol’ Opry was figuring out where it should be and these two [institution’s] histories intertwined for the first time. Can you tell us about that?

JH: That is true. I know it’s wild to picture this, but the Grand Ole Opry was originally taking place in a studio within the office building of the insurance company that started it, National Life and Accident Insurance Company. That was fine initially, but it became a problem, when [the show] became a popular draw.

And there was a time when people were lining up, clamoring to get in, and there were executives from [the insurance] company trying to get it, and the people in line thought the executives were trying to cut in line, so it caused some tension. Soon the quest for a more suited home [began].

In the mid-‘30s, the Opry moved for a couple of years to the Belcourt, which was then. Obviously, the Hillsboro Theater. And then it moved on from there.

JB: That’s some serious intertwining.

JH: Yeah, that’s the first time. I think some people may know that, but I feel like there are other more human aspects of their intertwined history that people may not know.

And that makes me curious what you have found in your research on the Belcourt this year.

JB: The second time is, like, 75 years later. In 1999, the Belcourt Theatre closes, and its future is uncertain.

Actually, at that time, there was a group of songwriters who were going to buy the theater and they had an offer in to [Jim] Watkins, who owned it at the time, because they knew the history of the Grand Ole Opry. And instead, Watkins sold to Tom Wills, a descendant of William Ridley Wills, who started the National Life Insurance Company, who started [WSM and] The Grand Ole Opry.

[Tom Wills] just bought it so that it wouldn’t go away. And so, the Belcourt right now would not exist without the Grand Old Opry.

JH: I do actually remember that era, because he not only bought the Belcourt, but he had quite the collection of vintage films and he would host parties. And I went to some of those parties. Those are the fun things that come with people putting their resources where their passion is in the name of the good of the city and its cultural institutions.

JB: It seems like the grand Opry is so well defined that it’s seen as rigidness. How was it able to define itself so thoroughly and was that the key to it’s success?

JH: It was not the first successful radio barn dance, but there was no such thing as country music as a genre or a format when [the station WSM and its show] the Grand Ole Opry began. So [the programming] was this grab bag. It was sort of based on convenience and availability and interest, because they were not paying people a lot.

They were bringing in [harmonica player] DeFord Bailey, a local performer who came from a long Black string band lineage of his family playing for dances. And [former vaudevillian] Uncle Dave Macon was from the area. The performers had to be able to get here. Those were the days when somebody might just pop up and ask to be on the show.

That was a wide open template, but really, [the Opry] was already gathering its ingredients. There were people doing kinds of comedy, there were people doing dance music, there were a lot of instrumentalists before they got more vocalists, and then string bands and eventually dancers on the show as well. Those are all ingredients all remain on the show.

What is on the Grand Old Opry is so much broader than what is considered country radio now. Because it is multi-generational, and it encompasses every era of country and what people think of as Americana music and folk-leaning singer-songwriters. It’s where string band music really gave rise to the development of bluegrass as a distinct style and they’ve continued to have a lot of different forms of bluegrass on there. There’s gospel. They still have comics and the Opry Square Dancers.

People think of it as a template that’s set in stone, but it actually is still a variety show. And when I sat down and talked with the guy who runs it, Dan Rogers, he joked that if you list all of those ingredients on paper, they would seem unlikely add up to a successful show, because that’s how broad it actually is.

I do there is this kind of intangible sense of what’s appropriate for the Opry or not, but there’s also a fair amount of leeway within that when it comes to different forms of performing.

I wanna about hear about the programming of what was then the Hillsboro Theater. That had to be completely different than what we know as the Belcourt now, right?

JB: The Belcourt now is Arthouse Cinema, but it has been so many things over its 100 years.

It’s done live theater, rather unsuccessfully, but time and time again, it has done it. And it also has done live music. And for a long time, it tried to do kind of all of these things at once, film, music, live theater. And really, it spread itself too thin and it shut down in ‘97 and ‘99 because people simply weren’t going. There were other places for them to go; two Regal Cinemas open up.

So the Belcourt had to redefine itself, and it found its niche in 2016, when they did the redevelopment and they started programming exclusively art house stuff. They weren’t going to compete with Regal, and they weren’t going to be doing the popular movie — which is counter to what you should be doing because you would think they should play things that are popular. But instead, they openly defied that by saying, “We’re gonna play movies that people don’t often like.” [laughs]

JH: That makes me curious: If the identity of the institution was sort of unsettled for quite some time, then what was its status in the city?

JB: It was still loved. It’s not defining Nashville to the broad audience that the Grand Ole Opry is, but it’s defining Nashville for the people here and for aa small group of people, it means a great deal.

JH: I hear people talk about it like it means the world to them, you included.

JB: I mean, it is respected and known by every person who knows movie theaters. I have [the] Criterion [Channel] and there’s a section on the Belcourt Theatre. It’s revered.

What has the Opry’s reputation in the city been over time?

JH: It’s evolved quite a bit.

WSM started out with a wide range of programming [beyond just the Opry], the high brow, the middle brow and the low brow. I mean, that’s how the music was perceived. We’re talking light classical and dance orchestras to old-time performers and pickers doing old familiar tunes. And the range of opinions about the programming were as wide as the programming itself.

There were people from further outside of the city who loved the old-time music, and they were very enthusiastic about it and wrote [letters]. They wanted to come see the [Opry]. There were people who lived in Nashville proper who complained, because they wanted to hear the more middle brow or highbrow stuff [on Saturday nights]. They wanted to hear something more refined and closer to classical music or more upscale pop.

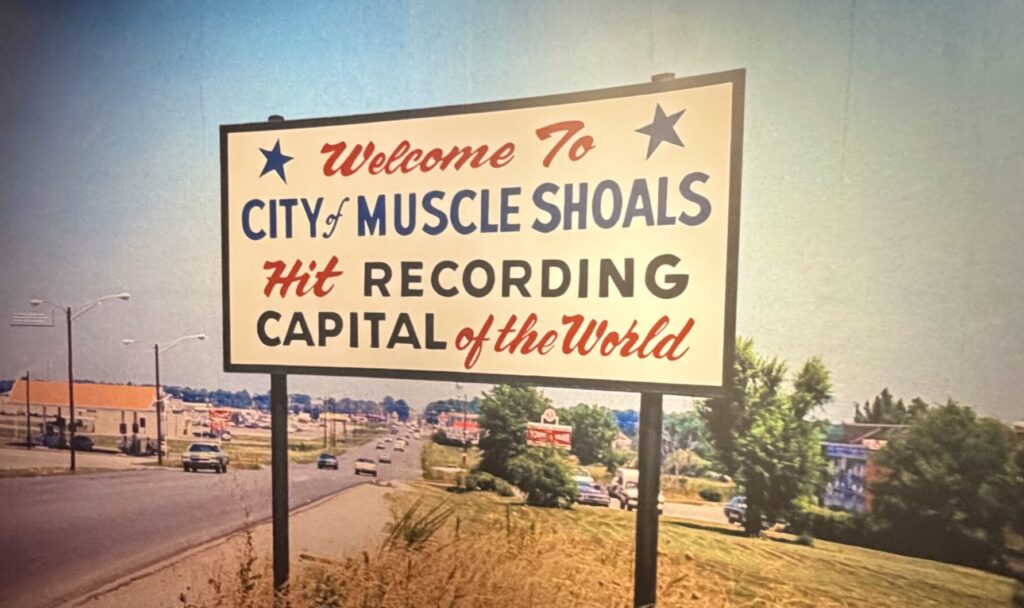

That tension actually persisted for quite some time. There was even a governor of Tennessee, Prentice Cooper, who was invited to a big celebration of the Opry a couple of decades into its existence. And he declined because he felt that it was bringing down the reputation of Nashville. It took a while for it to become an institution that merited its own signs on the highways saying “Home of the Grand Ole Opry.” That is a monumental change from people saying, “We wish this wasn’t here,” to claiming it and making it really part of the civic brand.

You mentioned different phases of the Belcourt shutting down, being redesigning, things like that. Technology for showing films, I’m sure, has changed quite a bit in the last century. So what has preservation of the institution actually involved?

JB: It’s repertory catalog — the movies that it playing that are movies that were released before this month — is huge.

There are some physical ways in which they show its history. There’s the 1925 theater. They have the projectors up there. But for most of the movies, they’re hitting play on a digital board. They have the capacity to show 35 millimeter, to bring in big reels, but mostly it is digital.

Their preservation is preserving the cultural history through its programming, having Robert Altman’s “Nashville,” playing Ernest [movies], you know, celebrating the cultural history of Nashville and of film by showing those films and bringing audiences in.

When it opened in 1925, the [entrance] was [where] the Villager Tavern [is now]. And now it’s, it’s around the corner, and they have done a lot. They used to have one screen, then it was two and now it’s three. They’ve done a lot to change it, but also to preserve some of those things.

The Opry has changed locations, but also has an interest in preserving culture.

JH: Preservation is kind of a complicated thing when you’ve moved around quite a bit, you know? The Opry has had probably more homes in Nashville than people even realize, because people tend to think of the Ryman Auditorium and the Opry House

The Ryman was the home of the Opry for a very long time, and through a really pivotal era in its growth in popularity, when it become a nationally recognized thing. And it was the star-making machine where performers on that stage were building national fan bases.

They did decide at a certain point in time that it was in such disrepair that they should maybe tear it down. And I think everyone is glad that they did not, in fact, do that. But when the Opry moved out to its newly built theater in the suburbs, in the name of preservation and continuity and symbolism, they cut a circle out of the stage floor at the Ryman and took it over to the new stage at the Opry House. That tangible piece of preservation has become so much a part of the brand that everyone speaks of stepping into the circle as the moment when you enter the lineage and the family of Opry performers.

And much like what you were saying about people who are themselves artists getting involved because it matters to them, there was a big public campaign on the behalf of the Ryman and Emmylou Harris recorded a live album there that did a lot to raise awareness and funds. Now the Ryman functions as a museum and a venue in the city where lots of different kinds of things happen.

JB: Both places have people who care who are running them and they do things that are special for their venues. And I think that’s inspiring the things that will make them both live on for a hundred more years.