Despite the fact that Gee Slab, one of the founders of Six One Trïbe, is a native of East Nashville, until just a few years ago, he had no idea that he was living in such close proximity to a stately recording studio called Eastside Manor. He has a clear memory of finally visiting the property for the first time.

“This feels like a castle,” Slab observes, ambling down the gravel walkway. “You see the big white doors and you see the open balcony thing, like a maiden’s going to come down, Rapunzel’s going to come down. You just feel like you’re not in where you’re at.”

Hip-hop has always been powerfully aspirational music, and Trïbe expresses that in its own, distinct way. On this fantastical property, Slab, a veteran emcee with a leader’s mindset, is working diligently to help make a reality out of the artistic dreams and professional ambitions he shares with his fellow Nashville hip-hop artists. Many are Black like him, and have long lived and worked in the shadow of a predominately white music industry that they’re well aware has nothing for them.

“I did manifest something like this in my head,” Slab recalls. “Was it gonna look like this? I didn’t know what it was going to look like. But a place where people would come together is important for this city, especially for hip-hop.”

What it looked like, it turned out, was creating the hip-hop collective Six One Trïbe with Eastside Manor studio manager, Aaron Dethrage. Since Dethrage happens to be a bearded white guy, he’s been drawing comparisons to archetypal hip-hop guru and Def Jam co-founder Rick Rubin. But it was hardly a given that Dethrage would end up helping build and equip a crew that’s determined to accomplish what’s long seemed impossible for hip-hop in Nashville; he grew up in small-town Alabama, studied at Belmont for a career engineering for bands on stages and in studios and first caught the vision for what became Trïbe from a travel show, of all things.

“Anthony Bourdain was my inspiration for all of this,” Dethrages reveals. “I really was always drawn to people that saw the things that made stuff special in niche settings. That is why I got into music in the first place. I wanted to find the smallest artists that could be the biggest artists and give them the opportunity to shine. Finding this hip-hop scene that has had to be so largely self-sufficient was kind of my first opportunity in town to do something [like] that. No one ever taught me at Belmont that you could work with rappers in Nashville. No one ever taught me how to work with rap music at Belmont. It wasn’t a conversation.”

In 2020, Slab put together a compilation of Nashville rappers and Dethrage started recording local hip-hop artists for a tornado relief project. Then, recognizing their shared investment in elevating voices from the Nashville scene, the two combined efforts.

“We’re raised from totally different places and don’t have no similar background whatsoever,” Slab observes, seated next to Dethrage in the combination library and studio control room of Eastside Manor. What’s important, he says, is that “our morals and how we conduct ourselves as people are very similar.”

Since Slab’s been building his reputation as a serious lyricist with a muscular flow in Nashville for more than a decade, he spread the word about recording sessions on Instagram, and people took the invite seriously and showed up.

In the past, Dethrage had recorded average-sized pop, rock and roots groups in the space, and the furniture facing the two monstrous, analog mixing consoles easily accommodated those sessions.

“But with these Trïbe sessions,” he notes, “we’ll have 25 or 30 people out here at a time. So we have our little stack of church potluck folding chairs out here that we have started keeping out, because they get so much use.”

He and Slab demonstrate how they typically set up for a full house, grabbing three or hour chairs at a time and arranging them in tight rows.

“Any day when the whole group is out here,” says Dethrage, “you’ll open up this door and it’ll just be a maze of people all kind of in their phones, writing different lyrics.”

Ronni Raxx, now a TRIBE member, wasn’t sure what to expect when a friend brought her to an Eastside Manor session. She was fairly new to filling a lead vocalist role, and wasn’t counting on others urging her to contribute.

“‘If you feel compelled, go in the studio and just sing your heart out or just rap your heart out.'” she remembers being told. “And [I’m] like, ‘What?’ That’s not that’s not the norm of a studio. You don’t just go in…”

Collaborating with the sizable crew on hand made just as much of an impact on another artist, Blvck Wizzle, who’d known Slab since high school and later joined him in the collective.

“Gee Slab was older,” Wizzle explains. “I was in the ninth grade. He was a junior. I was like, ‘You my uncle, man.’ And now I’m meeting other artists. The next time we come together, I’m excited to see people. My boy Negro Justice, aw yeah. I just met that dude, and I got so much love for him. There’s about 20 more people that I just met, and it’s real love.”

Wizzle got resourceful about home recording in high school, when he was in another collective: “We just had the basics, man. We didn’t have none of the right stuff that we needed, like good equipment. We were recording on a computer mic with a sock on it over at my house. “

Through Trïbe, the melodically agile, rapping R&B singer and psychedelic guitarist is releasing the first music he’s made in a professional studio, from group tracks to a forthcoming solo album.

The Trïbe ethic is to embrace people as they are. There’s no uniform way that its members are supposed to look, sound or carry themselves. Nor is their any pressure to keep their vulnerabilities out of view. Many within their number are quick to share that they never felt they fit in until they found Trïbe. That’s captured in the title of the group’s next album, Reset For the Rejects, due out in July. Some, like AndréWolfe, illustrate inner anguish, while Raxx relies on the collective looking out for her physical well-being: “Full disclosure: I have lupus. About a year ago, I started dialysis. So that is kind of a hassle that I have to deal with, while trying to do music as well.”

When the whole crew traveled to Austin in March to showcase at the South By Southwest festival, her dialysis was factored into the schedule. Dethrage says that ensuring the trip, a first chance for exposure as a massive industry gathering, would be affordable and accessible for everyone was top priority.

“A big part of this for me personally is just always trying to make sure that the experience is the same for everybody,” he reflects. “There’s just so many people; I never want people to feel like they’re being excluded, because something is harder for them than it is for other people. I don’t want people to feel like there’s like a hierarchy.”

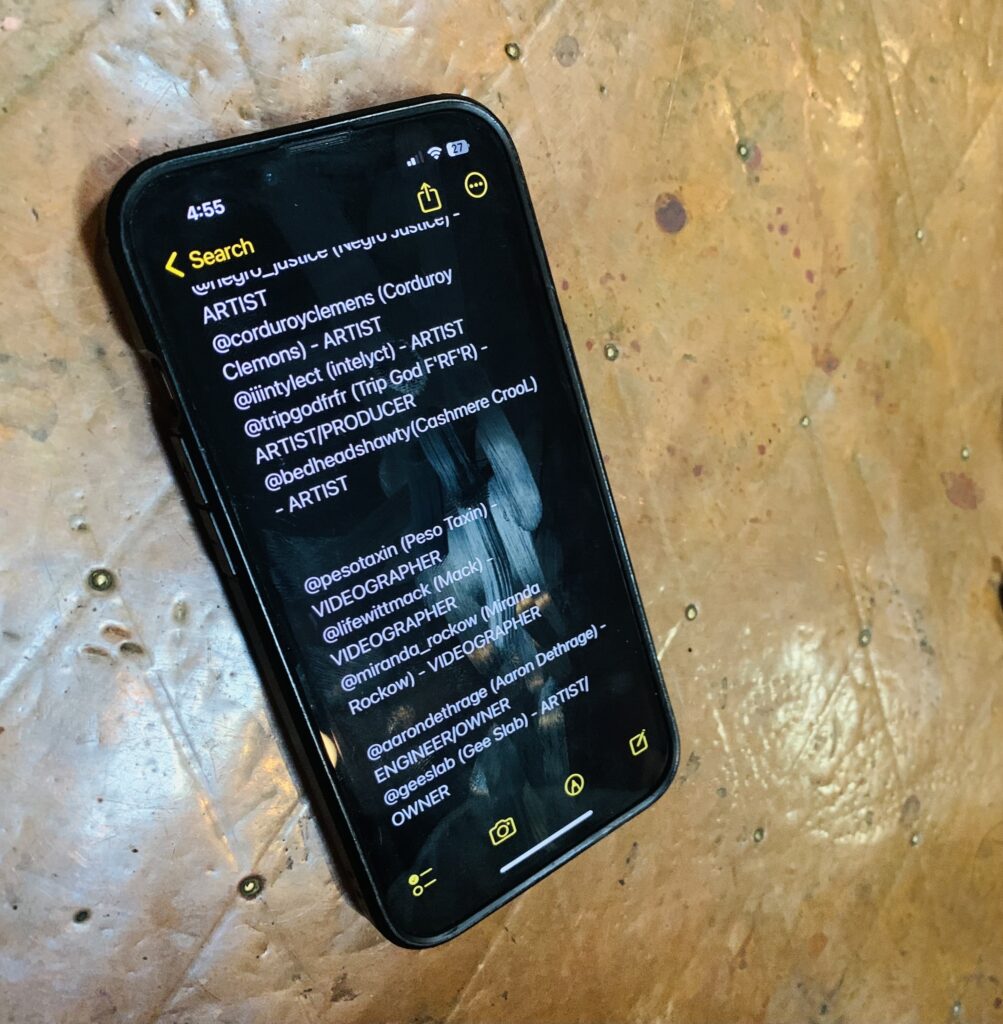

At the moment, Trïbe has a whopping 16 members. Ask Gee Slab how they keep track of who’s part of it, and he opens the list he keeps on his phone to avoid inadvertently omitting anyone’s name, or the role they play in the group.

Just last week, Trïbe entertained the late-night crowd at another major festival outside of the city: Bonnaroo. And the SXSW appearances led to show bookings in Indianapolis and Milwaukee. Slab says that’s exactly the sort of expansion they’re working toward. “This can’t stay local,” he insists. “It can’t only be in Nashville. They are too deserving for it to stay here. We’re supposed to be in L.A., New York, Beijing, across the world. This is the greatest show on earth to me.”