Record Review

Often, when a contemporary artist pinpoints the soul era as the source of inspiration for her music, she’s indicating a certain vocal approach: strenuous, full-throated testifying, the kind of singing for which Aretha Franklin embodies the ideal. That’s not really what Dominique Fils-Aimé had in mind for her latest album, Three Little Words—the third installation in her chronological study of Black American musical innovation—even though she’s described it as bearing the influence of soul.

The Haitian-Québécois singer, songwriter and arranger is considered a rising star in vocal jazz; that’s the category in which her previous album won a JUNO Award—the Canadian equivalent of a Grammy—last year. But she relates to jazz more as a mindset, one that’s wide open to elegant vocal exploration. Her own voice–reedy, lustrous and continually fanning out in downy harmony, sculpted counterpoint and frisky licks that could easily be played on instruments–is her most important accompaniment.

Among the 15 songs on Three Little Words, there’s just one that Fils-Aimé didn’t compose: Ben E. King’s plea “Stand By Me.” But her interpretation of it stands out from hundreds of others in existence; her version begins and ends in a minor key, in melancholy acknowledgement that the noble steadfastness she’s singing about is elusive. Her decision to re-do that 1961 R&B-pop hit is a clue to the sensibilities that drew her fascination.

In her own poetically economical writing and impressionistic arranging, she riffs on the effervescent, collective vocalizing of doo-wop and girl groups, the teen music that preceded and stood to the softer side of soul. Songs like “While We Wait,” “You Left Me,” “Mind Made Up” and “Home To Me” recall the chipper interplay of those ensembles, only Fils-Aimé, supplying all the vocal layers herself, sings with wise, supple restraint. Even during “Love Take Over,” her churning, rhythmic call for a relationally and socially transformed world, she sounds patiently insistent, a believer in nudging and nurturing her vision into existence.

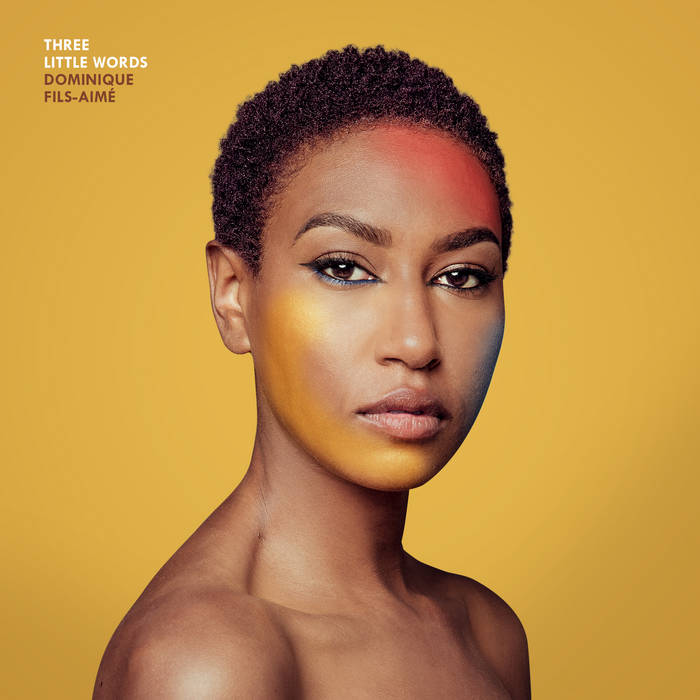

Artist: Dominique Fils-Aimé

Project: Three Little Words

On the Record: A Q&A with Dominique Fils-Aimé

Jewly Hight: I know you’ve had the vision for Three Little Words for years, since it’s the third in your trilogy of albums. When and how did you go about recording it? Was the pandemic a factor?

Dominique Fils-Aimé: I had already written the songs for Three Little Words, and we were getting ready to get into the studio when the pandemic hit. So we had to delay it a few weeks. Getting to sing them after felt strange, because the album was talking about hope and light and new beginnings, and I could not expect how accurate and relevant, actually, those elements would be in my own personal life. It was what I needed to hear. We were not able to record all the musicians together as I had hoped. So that’s one of the elements that the pandemic basically changed. Aside from that, it was just the mood that was different.

JH: There are so many different ways that you move between languages, as a French speaker who writes and sings in English; a vocalist who uses her voice to illustrate parts that could be played on instruments; someone with synesthesia incorporating the blending of sensory impressions into your work. Could you help us picture what each of those aspects of your artistic process are like for you? How would you say that you explore the possibilities of communication?

DFA: From colors to sound to languages, from French or English, to me, it always felt like one single thing. It’s communication and frequencies, whether they’re the vibration of the colors or the frequency we emit as humans, with our vibe, with our sound, with our voice. To me, they’re all one thing, really, and it’s us trying to share and connect, express emotions one way or another. I don’t really see any boundary separating them. I often feel like they kind of overlap each other, in a way. I wouldn’t be able to divide them and put them each in a separate box.

JH: In the chronology of Black American musical innovation that you follow in your trilogy, you’ve described the new album as being inspired by the soul era. Often, when artists speak of drawing inspiration from soul, what they have in mind is the sort of strenuous singing and testifying that Aretha Franklin and Otis Redding were doing in the ’60s. But when I listened to your writing, arranging and vocal delivery on the album, it seemed as though some of your reference points were the music of singing groups of a slightly earlier era. What inspiration did you find in the energy and vocal interplay of doo-wop and girl groups?

DFA: I feel like I had to underline the impact girl groups and doo-wop had on my vision of Motown and soul music; it’s the first step that I kind of took in that direction. And when I discovered girl groups, I was really drawn to how they would harmonize each other, support and echo each other’s words, the way they would really powerfully punctuate a song. I think it was the fact that they kind of became somewhere between singers and musicians in a way. So they would be part of the backing track as well as the lead vocal support. I found it pretty interesting, and I always wanted to try, even alone, to harmonize and discover the way we could use our voice to create an instrument. To really use it as instrument it can be sometimes underrated.

JH: I’ve heard lots of performers do versions of Ben E. King’s “Stand By Me.” Your interpretation stands out. When you go from minor key to major and back to minor, it introduces a sense of doubt into the song. How did you want your interpretation to change the story told, the emotion conveyed in the song?

DFW: We decided to do “Stand By Me” minor, major, minor, just so that we could, indeed, create a new mood to the nighttime aspect of the kind of fear and hope that someone will stand by. Also that wave of down, up, down was the best way for me to create a natural transition that would lead us back into the beginning of the first song of the first album, which is “Strange Fruit,” in the notion that history kind of repeats, although it’s never exactly the same, the same way it will not be the same listening to one song twice. It will have different meanings, depending on what you just heard before, the fact that it’s not the first time you hear it anymore. So I wanted “Stand By Me” to be the song to create that link and that wave of uncertainty that lies inside the lyrics of the song, but were never present in the major version of it.

JH: “Home To Me” has some lovely melodic counterpoints and harmonies, all created and sung by you. How did you use your vocal parts to deepen the sense of solitude in the song?

DFW: “Home To Me” is meant to reflect that moment at night when we’re confronted with ourselves and we go through our day [get] introspective and think about where we could have done differently or how we feel about certain things we did. And I wanted the voices were used to be different because it’s a more delicate song. It’s a more intimate song. Instead of layering a lot of voices, it was more about placing the voices in space from left to right, a bit more in front, a bit more back, and lonelier each of them. So they were kind of an echo bouncing inside the head the same way they bounced around inside us as we listen to them.

JH: How did you place wisdom front and center in the vision of freedom and change that you lay out in “Love Take Over”? Do you consider it to be a song of optimism?

DFA: In “Love Take Over,” I present a dream that I have of a revolution that is based on love and empathy and communication dialogues, instead of the monologues we may find on social media right now that are contributing to how divided this world is. And when I talk about wisdom, it’s also just the basic humanity that may be found in all of us. So there’s something universal about wisdom. If we really follow our instinct and try to tap into the collective memory and source of knowledge, some things are just instinct and basic humanity that should be more present in the way we interact with each other. Some people will say I’m an optimist, but to me, that’s my reality. So to me, it’s realistic. A revolution based on love might feel like something optimistic, but it could also just be the reality we decide to create. And that’s the beauty of art, is that we get to create reality first in our minds and who knows when one day it might become something physical and actually integrate the hearts of people who hear it and have a ripple effect. So we can only do our part in the best way we know how.

JH: Who or what do you see yourself as speaking to, exhorting, encouraging in “Grow Mama Grow”?

DFA:”Grow Mama Go” is meant to give a little sunshine in anyone’s day and encourage anyone who needs a boost. But there is definitely a special mention for the new generation of young girls that is growing up right now and really showing us, pointing fingers are the things that don’t make sense, speaking up about the causes that they hold dear to their hearts, and they are the future, for real. It’s just insane how amazing and smart they are and the things they’re doing. I feel like we should give them all the tools to help them keep the change and build that world that they see, because it seems to make a lot of sense. And all the encouragement we can give them, they fully deserve it.