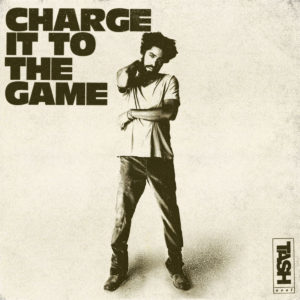

The term “Charge It To The Game” means something is a loss, but a lesson is learned from it. Singer/guitarist Tash Neal took those lesson from his personal experience and unpacks them on his debut solo album “Charge It To The Game.”

Project: Charge It To The Game

The album self-produced by Neal except for two songs “Like A Glove” and “Catching Up” produced by Dan Auerbach of The Black Keys. Neal uses personal lyrics with a hard rock and 70s soul sound taking a page out of the Sly Stone playbook.

Neal drives deep into his personal adversity from his near fatal car accident in 2012 that left him in a coma and missing a section of his skull. From the death of his father months later and the continued fight for social justice, Neal unpacks all his feelings on his debut solo album Charge It To The Game.

The former frontman of the New York garage duo The London Souls used the time between rehabilitation and recovery to pen his pain and become a stronger songwriter only to realize the music he was writing at the time wasn’t going to fit the style of the band.

When you listen to “All I See Is Blood” about the accident, “Finding Your Way” about the death of his father and “Something Ain’t Right” an upbeat battle cry for social change after the murders of Philando Castile, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, the album is personal, angry, and revealing the man behind the guitar while the music is packed behind a heavy-groove like he is playing the guitar like it’s his last time.

On the Record: A Q&A With Tash Neal

Marquis Munson: I know 2020 wasn’t the year everyone expected. So how is your 2021 going so far, with the album release?

Tash Neal: I don’t want to hype about anything right now, but I feel blessed. But you know, I’ve been feeling that way, which is kind of funny.

MM: I love the album title. Charge It To The Game, that was something my mom used to tell me all the time growing up. It basically means something is a loss, but you learn a lesson from it. Was there a lesson being learned as you were approaching this album?

TN: That’s a really good question. I actually had a different title I was thinking of. When it became clear what this album represented, in terms of it being so specifically about the accident, life and death, “Charge It To the Game,” which was a song that was on the album, felt like it summed it up. You got to just keep it moving when you get hit with some bad stuff, and even hit with some positive stuff.

MM: Who were some of your earlier influences coming up in music? And did you circle back to those artists when making this album? When I listened to your album, I heard elements of Sly and the Family Stone.

TN: I spent so many hours listening to Sly and the Family Stone, so that’s going to be in my DNA. I remember the day I heard “Stand!” for the first time. His level of production and that sonic quality in terms of the groove was super influential. I think because this was a personal project, my project, I could really focus on sonically what I wanted it to feel and sound like. So I think those influences are able to be heard sonically on this album more than maybe earlier on The London Souls records, even though we were also influenced by that. I really took the time to make the grooves as heavy as possible.

MM: I’m glad that you mentioned “Stand!” When I heard “Something Ain’t Right,” it took me back to that song just a little bit. It had an up-tempo feel to it, but it still had the same message. I noticed over the last few years we have songs like “Alright” by Kendrick Lamar. These are battle cries for change that are really uplifting. What made you take that approach?

TN: It was written in a moment. It wasn’t even a choice. I was watching the murder of Philando Castile when I was writing the song. I had literally seen the murder. I was sad, I was crying. I was upset because his little girl’s in the back seat. I was like, ‘They are really out here barbaric at this point.’ But that was the riff that came out, and that wasn’t going to change. So I just kept the vibe and then lyrically was able to express what I wanted to in relation to that.

I don’t really dig slow, depressing songs when we’re talking about our situation as Black people on the planet. I feel like we have to be direct. They’ve seen us be murdered. We don’t need to be sad all the time. We can still express our joy within the music while saying real things at the same time.

MM: I think there’s three ways for black artists that have shared their message. When you go back to Sam Cooke’s “A Change Gonna Come” or Marvin Gaye’s “Inner City Blues,” the way they sing those songs you can feel their pain on the record. But then on the other side, you have Tupac and Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power.” It’s more aggressive. Then you hear uplifting songs. I hear all three of those different elements; I hear the pain in your voice when you sing that song. I can also feel that anger within you as well. But when you listen to the groove, it is uplifting.

TN: That makes me really happy. To be transparent, that was the angriest bass playing I’ve ever played. I remember playing in a studio and I wasn’t happy, but it was upbeat. But I brought the energy that I felt in writing it when playing it and I’ll never forget that because I was upset.

MM: Was that the first song that you wrote for the album?

TN: It actually wasn’t, but it was the first video made. Once the summer happened and people were forced to see the murder of George Floyd so inhumanely, and obviously the pandemic, we all had to pause, so you really had time to think, for better or worse. So I decided to make a lyric video that I suggest everybody watch, because I think the words are important in the song.

But actually, after the accident, “Boomerang” was the song that [told me], “This is going to be a new batch.” I knew that was a different style of writing than I’ve ever done. I never come up with a verse vocally like that ever where its kind of like not rapping but sort of spitfire vocals.

MM The song “Finding Your Way” discusses the struggle coming to terms with your father’s death. What was the feeling like writing that song?

TN: It was super sad, I got to be honest. I wrote that song in the other room while I knew he was deteriorating. I wrote it maybe a month before he passed. It was sad, because you always want to hold on to hope. And coming from the situation that I came from personally in a near-fatal car accident where my survival was a miracle, you can’t help but hope for another miracle because you just witnessed one. But that miracle, unfortunately, did not come in that situation.

I kind of wanted to write from maybe outer space or something, talking about humanity, how we need to get better as people, but probably talking about myself because my father’s in the other room and he’s passing. I want to be a better person for that legacy. I’m really glad that I have music, because that was such a therapeutic expression of that pain that I didn’t have to do other things to express that.

MM: I lost my father in 2014, and you tend to find ways to cope with it. It seems like you basically coped with it by coming out with this amazing project. I’m pretty sure if your dad would have heard “Something Ain’t Right,” he would be like, “That’s my boy speaking the truth, taking me back to my days of listening to Marvin Gaye’s ‘What’s Going On.’”

TS: Oh, man completely. He’s featured the lyric video, because I mentioned him in the second verse. His cousin is Kathleen Cleaver is also my cousin is Eldridge Cleaver’s wife. So the Black Panthers are really important to the family. I often think he would have been like “Man, you really learned something.”

MM: I watched Kendrick Lamar when he performed “Alright” at the BET Awards standing on top of the cop car. A whole bunch of news outlets just completely bashed Kendrick Lamar [for that]. And I’m like, “Have you heard To Pimp a Butterfly?’ It was a very uplifting album for black people. But you’re ignoring that and you’re condemning this song as controversial.” Why do you think when Black artists speak out on these issues in their music, it is deemed “controversial?” How do you get around that and speak on these issues?

TN: I try to keep perspective historically. These same outlets that would criticize Kendrick Lamar. But they won’t condemn the officer who has knelt on someone’s neck for nine minutes straight and murdered them on camera, whose oath it is to protect and serve, who’s paid by the people to protect them.

Black artists speak about the truth and inequality. White supremacy is an aggressive system, and a lot of times people claim ignorance. You can’t not know when you have generational wealth to inherit. You can’t not know when you see your school, and it’s quote unquote good, but you also notice the lack of diversity.

I try to focus on how far we’ve come. I feel so fortunate that we have all this access to great information and all this access of footage of people like James Baldwin, Angela Davis and luminaries like Malcolm X.

MM: To switch gears, I always say that music is healing for the soul. You’ve discussed being in a car accident in 2012 that left you in a different place physically and mentally. What impact did that experience have on you that you wanted to share musically?

TN: It was the single most defining period of my life, because I’m both physically and mentally a different person. They put me in a coma and I wasn’t supposed to make it. When I was in the coma, I was obviously separated from my body that was a different kind of spiritual experience. But physically you’re messed up because that was a really bad accident.

Obviously, living without half your skull has its own painful side effects. There’s a lot of things you don’t think about, like when you bend over that’s painful. Nothing prepares you for that. But thankfully I had family around me to help me through that, family and friends. That’s how lucky I am, because if I didn’t have that support, I don’t know if I would have recovered. And if I didn’t have music, I definitely wouldn’t have recovered. I had such a fire when I came back from the coma and I was like, “I got to play as soon as possible.” I think I had a different hunger to be out there. Once I was out there again, I played like it could be the last show, because I just went through that almost being my last breath.

MM A lot of times when songwriters use physical and bodily imagery, they mean it metaphorically. There are literal layers to the blood-and-guts imagery that you use during songs like “All I See is Blood” and “Bye Bye Bones.” What drew you to writing that way after the accident?

TN: I try as a songwriter to not be literal most of the time. But I felt blessed because these were really authentic, in-the-moment situations when I was writing the song. When I woke up from the coma, I thought I had an eyelash in my eye. I was wiping out for weeks and it was driving me nuts. Finally I see an eye doctor who’s like, “No, that’s blood.” I still see blood to this day. So it came really in handy to have that feeling like I saw blood for real, because these folks almost killed me, but I also literally see blood, which also is upsetting. “Bye Bye Bones” is actually like a thank you note to my family and friends and anybody that wished me well and also an expression of trying to come out of the coma musically. Another literal situation: I literally say one life ended when I said goodbye to half of my skull, and then another life began.

MM: There are some Nashville connections to your album as well. Dan Auerbach produced a few songs on your album. How did all of that come together and what was it like working with Dan on the record?

TN: It was dope. Shout out to Easy Eye Studios in Nashville. I love Nashville. I love playing Nashville. I love the musicians in Nashville. Life is cyclical, right? So years before that, I became close with Damon Dash in New York. He started working with The Black Keys. They were working with rappers at the time. So we ended up hanging out. Then years later, I was looking for producers and just the timing worked out and he was down and it was dope. I was really great to just be around that kind of talent, see that process and soak it in.

MM: Why is it important to you to find and surround yourself with Black band members in your solo work?

TN: I sort of felt there needs to be more representation. There hasn’t been that many Black bands—Living Colour is incredible—but a band that does rock and roll recently.

I meet this cat, Matt Godfrey, keyboard player, and I’m sitting there and I’m floored and my mind is blown and we start playing together. Every time we play, it’s a rocket ship. I did not know that he happened to have brothers. I didn’t know that his brothers played instruments. So Jordan’s on the drums, incredible. Dave, incredible guitar player, incredible singer, incredible bass player. The talent was there and it was perfect for the time and what we were collectively feeling. We all feel the same way and we have a sort of immediate familial connection, even though they’re obviously already brothers. But we ended up finding out a lot of funny things, like we all share the same middle name, which is bizarre.

MM: I’m glad you mentioned Living Colour and the Black rock and roll experience. How do you see yourself reasserting that rock and blues music are places where Black voices belong, genres to be reclaimed? And why does that matter to you?

TN: It’s almost like we are being collectively gaslighted when there’s so much revisionist history. People forget who invented rock and roll music. I don’t think people really, really absorb what Big Mama Thornton contributed, what Chuck Berry contributed, what Little Richard contributed. I could go on. But the folks that get paid, that really benefit from the music, they don’t look like us. I think it is so important to remember that factual history is in terms of where this music comes from and to not be discouraged. I grew up playing guitar. There weren’t people that look like me playing guitar, which was wild because I should have a big stake in this music. Matter of fact, I should be immediately connected to that, and that was not the case. So it’s crucial to me to always speak out and be clear about what it is. If I can represent in the music and on stage visually, definitely that’s what we’re going to do.