Guitar-slinging singer-songwriter Cidny Bullens has led quite the life, but he wasn’t convinced that his story was ready for the full-blown book treatment until he transitioned to living as a trans man at age 60 a little more than a decade ago. He finally commenced work on his memoir, My Life as a Cosmic Rock Star (out June 6 on Chicago Review Pres), after he and his wife Tanya Taylor Rubenstein relocated to a one-story ranch in Nashville just before the pandemic lockdown in 2020.

For Bullens, it was technically a return to Tennessee, where he’d spent stretches of time collaborating in the songwriting community back when the world still saw him as a woman. “I didn’t feel as a trans person that I was walking into a place that would not be accepting of me,” Bullens reflected on his porch about that most recent move. “In my head, I was still a songwriter.”

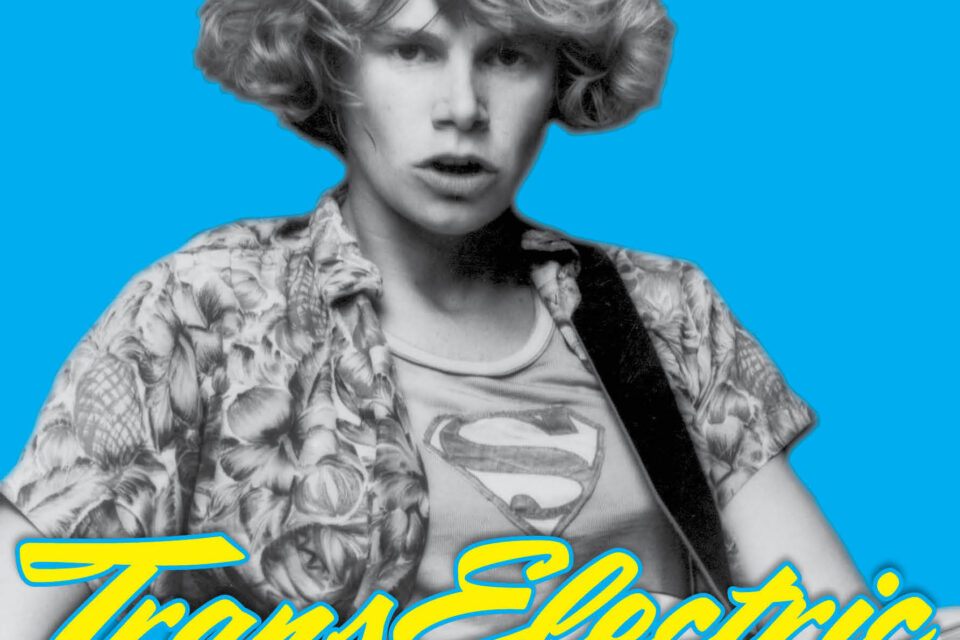

He’d been writing songs since the ’70s, when he worked his way into supporting roles on an array of blockbuster projects and tours and debuted his own vigorous, guitar-driven power-pop. All along, he drew on firsthand emotion. “It’s going to sound trite,” he offered as a caveat, “but I write from the heart. I don’t pull any punches.” It was only much later that he delved into distinctly autobiographical territory, shaping a 1999 album around the loss of his 11-year-old daughter to cancer, then creating a one-person show in 2016.

That production, which he performed in numerous cities including Nashville, boiled his experiences down to captivating bursts of detail. A sample line? “Man in a woman’s body. Mother of two. Married to a gay man. Living in Westport, Connecticut, right, smack in the middle of the Gold Coast. Driving a minivan.”

The next task, in Bullens’ mind, was to further flesh out the narrative in a book. “Of course, I had to mine more stuff,” he noted. “I had to drag out the old journals.”

He’d been scribbling down his observations, monumental and mundane alike, since the start of his music career. Disappearing into his office, he returned with a composition book whose pages were yellowed and loose.

“April 14th, 1976,” he read from an entry. “747, Flight 768 in London, England. E.J. beside me.”

“Who’s E.J.?” I prompted playfully, knowing full well that the answer was Elton John, who agreed to write the foreward to TransElectric, but wanting Bullens to have a chance to name drop.

“And then it goes into arriving,” he went on. “Several photographers were at the airport, as Elton said they would [be]. Little did I know that we would be on the front page of the two evening newspapers. And it says I’m Elton’s new American girlfriend.”

Bullens related that journalistic misperception wryly. Overall, though, he’d found it difficult poring through his handwritten accounts, and mused that he may someday burn them.

On the other hand, he emphasized, “I could not have written the book as it is now without the journals, because not only did it bring immediacy to the book, it brought everything back to me, what my choices were, how I behaved, how naïve I was. It also brought an empathy. I was just trying to live. I was just trying to get from one day to the next.”

We are, Bullens recognizes, living in an era when rock memoirs outsell all nearly all other volumes written on music: “Here’s the bottom line for me with the book: It’s an interesting story about a rock and roll life, right? But it also happens to be [informed by the fact that] I am transgender. I mean, I really did know at three years old. What I was trying to say is it impacted everything all the time.”

He pointed to a parallel in the lyrics of his song “Walkin’ Through This World,” soon to be reissued on an album through Kill Rock Stars Nashville. “You can’t see me now, and you couldn’t see me then,” he declares with gravitas over the track’s roots-rock guitar jangle, “but I’ll keep walking through this world as exactly who I am.”

Bullens’ certainty that he was in the wrong body was a constant, but his understanding of what that meant and what to do about it grew over time. “I talk about looking into transition when I was in New York City, going to school,” he said of book passage. “In those days, there was no word ‘transgender.’ It was ‘transsexual.’ There was not one person I could talk to in my world about who I felt I was. So I shut it down.”

Throughout the memoir, we see him carrying that self-knowledge with him through his attempts to break out as an androgynous rock performer and his years mothering two kids and a myriad other seasons of life. “So the thread of me being who I am until my old age is important,” he concluded.

In 2020, Bullens recalled, “I wrote the book without really thinking about too much the state of the world.” His mind was on nailing the narrative of his journey and doing justice to its complexity.

“Try to put my life in a box,” he challenged, as if speaking to society as a whole. “Which box are you going to put it in? Yeah, you can put it in the transgender box. But, oh, I’m a mother. Oh, I’m a bereaved parent. Oh, I have grandchildren. Oh, I was a rock and roller. Oh, I’m a songwriter. And we all have so many things that we are. My being transgender is one of the things I am, just one.”

Even though his approach to memoir was long in the making, he realizes that publishing it now, at the age of 73, in a year when Republican lawmakers in his state and many others have taken aim at transgender rights, has humanizing potential.

“And here we are today with the vitriol, the hate, the laws being passed, anti-trans sentiment,” he catalogued. “Yeah, I’m showing up in public as a trans person, now, in Nashville, Tennessee. On the other hand, I’m showing up as somebody who has a story. If I can be a vehicle for someone having a little bit more of an open mind about the humanness of being trans, then my work is complete.”