It was a bootleg copy of the album Jackie Shane Live! — so fiercely alive with soul-shouting dynamism, theatrical command and testifying immediacy — that first grabbed Canadian filmmaker Michael Mabbott.

“It just felt like Jackie was talking to me directly, like I was the only person in the room,” he says. “There was very little information about Jackie at the time when I started listening to her, and I needed to find out more.”

He searched until he found her phone number, and began calling her at home in Nashville. She’d regale him with such colorful tales and resolute philosophies from her life that he couldn’t take it all in, eventually asking for permission to record what they spoke about.

And during those conversations, Shane, a film buff, began laying out her own ideas for a treatment.

“I just could never have conceived of what a film about her would be like until we started talking,” reflects Mabbott. “I think for Jackie, a very private and, in some ways, very guarded person — and somebody who was in absolute control of how she was presented — it was an exercise in trust and collaboration to some degree.”

Before he could travel to the U.S. to meet her in person, she was gone, passing away in her sleep in early 2019.

There’s a microgenre of documentaries about tracking down people who’ve disappeared from public view. Think of the Oscar-winning “Searching For Sugarman,” more than one movie titled “The Artist Who Disappeared” or the podcasts “Missing Richard Simmons” and “Finding Matt Drudge.” They’re variously framed as investigations getting to the bottom of previously celebrated figures’ current elusiveness, a construct that can require quite a bit of conjecture and projection.

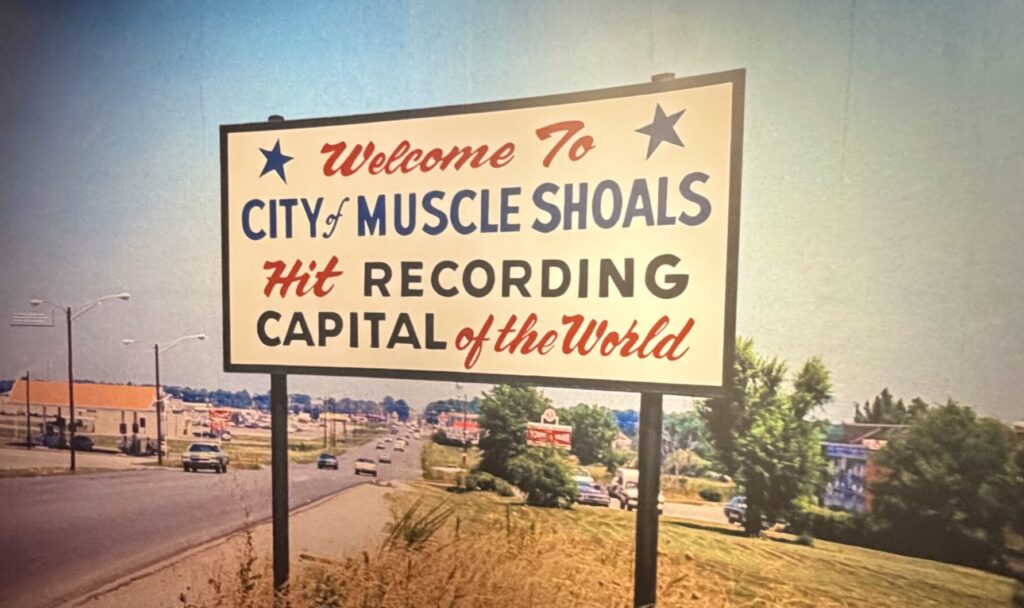

A new film called “Any Other Way: The Jackie Shane Story,” premiering at both the Country Music Hall of Fame and Nashville Film Festival, turns that template on its head. Its subject — a riveting, visionary R&B performer and Black, trans woman who got her start in Nashville, then took the Toronto scene by storm in the 1960s, before completely falling off the radar — had not only been located. She’d actually weighed in on the proper approach to telling her story. So the filmmakers felt the weight of her wishes, but no longer had her around to help. Ultimately, they had to figure out how to do justice to a thoroughly self-directed performer who’d rarely been seen for who she was during her lifetime.

‘We will protect her’

Shane’s surviving nieces, Vonnie Crawford-Moore and Andrenee Majors-Douglas, didn’t know that she existed — much less lived a mere five minutes away from them — until they received a Friday night phone call from an unrecognized California number informing them that she’d passed.

“The first thing I did,” says Crawford-Moore, seated on the couch in her North Nashville living room,” was go to the internet to research what was being said to me. (Her photo) popped up, and it was like, ‘Oh, wow!’ I quickly saw the resemblance.”

Majors-Douglas chimes in next to her: “To have to go to the morgue and identify a family member that you never heard of, it was a lot. It was a whole lot.”

They had only a few days to clean out Shane’s home. Inside, they discovered that she’d preserved plentiful fabulous, vintage costumes, but it wasn’t yet clear that those could be coveted artifacts. Tucked in the back of her closet, wrapped in newspaper, was a handwritten memoir.

Crawford-Moore read the whole thing, taking in her aunt’s voice and vantage point. “You cover all these different emotions in her own words for her basically to get to the point to say, ‘All I wanted was just to live a normal life. I was a woman born in a man’s body. I just wanted to be me. I give love. I just want love in return.’”

The nieces learned of the cruelty their kin endured: The racism that followed her from the Jim Crow South to the entertainment industry. The transphobic ridicule she faced, including from her own stepfather. And Shane’s heightened awareness of threats to her existence — she only stepped out to check her mail in the middle of the night disguised by sunglasses and armed with a gun.

The nieces might have been caught off guard by the barrage of requests for access and rights to the songs, stories and stuff that Shane left behind, but the fact that their aunt was so vigilant about protecting herself told them what they needed to know. “I think that people thought that we were going to be dummies, not intelligent, degreed people with sense,” says Crawford-Moore. “We just found out we had a family member who lived as a recluse who had gone through so much adversity. They quickly found out what kind of family we were, how we listened and observed and was able to sort through. We will protect her, and we will not allow anyone to mistreat her, misuse her, exploit her on any level anymore.”

“What we had to do,” adds Majors-Douglas, “was weed those people out that were the snakes and the bad people, and we ended up with a good bunch of people at Banger Films.”

‘How do we use these pictures?’

“They were extremely cautious,” Mabbott affirms, “and I’m so grateful, in retrospect, that they were, because they clamped down on all of Jackie’s things and just very calmly and methodically walked through.”

Mabbott found a filmmaking partner for the Shane project in Lucah Rosenberg-Lee, who’d taken care in telling stories of other Black, trans lives, including his own.

But it was a towering task to get the documentary made, or even funded. They were told a trans protagonist was too niche. And there was almost no footage of their subject. She’d declined invitations to perform on “The Ed Sullivan Show,” which mandated that she couldn’t wear makeup, and “American Bandstand,” which only wanted white youth dancing on camera, making her lone television appearance on the Black, Nashville-based variety show “Night Train.”

“When we started,” says Mabbott, “we were making a film whose star and hero was no longer with us, who had done one live (on-camera) performance, and there was nothing else. We didn’t know what kind of photo archive we would have, and that was a huge challenge, how to make a film like that.”

Among the mementos that Shane’s nieces had stowed in a storage space, the filmmakers were relieved to find numerous photo albums. The images captured her Nashville childhood and early days of performing on Jefferson Street on through her Toronto heyday and off-stage years, and the way that her presentation of femininity evolved.

“So for Michael and I,” says Rosenberg-Lee, “it was like, ‘She left this stuff for a reason. How do we use these pictures in a way that conveys what Jackie was going through? How do we use them in a way that tells a chronological story? But also how do we do it in a way that is respectful and isn’t just exploitative of the trans experience?’”

They had the “Night Train” clip, but beyond that, capturing the power of Shane’s live performances — which they’d only heard about from people lucky enough to catch her shows — was a tall order. They needed to add visuals to Shane’s live recordings and phone calls. They asked actor Sandra Caldwell and drag queen Makayala Couture, both Black and trans themselves, to do reenactments for a century-old style of animation called Rotoscope.

“The base of the animation is shooting them on a green screen,” Mabbott explains, “and they’re lip syncing. You can only imagine the talent and work that that would take on their behalf, to bring that to life. It’s extraordinary.”

In the movie, Caldwell and Couture also read from Shane’s memoir and place their own lived insights alongside it.

‘She did have that agency’

“Any Other Way” acknowledges how wrongly Shane was treated, but never for one moment portrays her as a passive victim. Instead, we see her making her own decisions. A young child joining the adult choir at church only if she could slip out of the service before the sermon. A teen turning heads in Nashville’s R&B clubs, who left to pursue her potential elsewhere. A Toronto sensation who walked away from music, and eventually returned to a quiet Nashville existence out of a sense of duty to ailing elders in her family.

“When she left the stage and became a recluse,” says Mabbott, “it was, by and large, so she could live the life that she wanted to live. And she was willing to accept the consequences of not being on the stage anymore, of not being a big star, of not playing ‘Ed Sullivan’ in order to be true to herself.”

“From the beginning, it was really important that people understood that she did have that agency,” adds Rosenberg-Lee. “That led her story and then, by default, led the film.”

Shane’s nieces gave interviews about their own choices to look out for their aunt’s legacy. But they didn’t know what made it into the film until the Toronto premiere.

“We never saw it early,” Majors-Douglas makes clear. “We didn’t want to see it early. I think what made us cry was all the people that came up and said, ‘Thank you. This is our life. It’s a story about us.’” It’s also the committed account of an absolutely singular existence.