Pop music has its expected moves, its reliable strategies to get a musical payoff by making the melody’s apex the main event. Torres isn’t interested in reserving her intensity for the high notes. She engineered the chorus of “Don’t Go Puttin’ Wishes In My Head,” a muscled-up power-pop song on her ravishing fifth album, Thirstier, so that it has a dramatically shifting center of gravity. Mackenzie Scott — the singer-songwriter, instrumentalist and producer behind the moniker — leaps up to deliver reedy bursts of syllables, then plunges into guttural gravitas an octave below, repeating the vocal maneuver a couple of times more. She attacks the melody heartily in her upper and lower registers alike, which gives her delivery a vertiginous quality. And for her, it works.

The fact that a Torres song can be said to have a robust hook at all marks a greater upending of expectations. For her first four albums — the initial one self-titled and self-released and the rest on a rotating cast of indie labels — she worked from a posture that seemed at once contemplative and oppositional. “I definitely have a lot of that in me, that resistance to doing the thing that’s popular, the thing that people want from me or want in general,” she deadpans from her New York apartment. “I’ve really done a lot of not wanting to give the people what the people want.” It’s exactly those kinds of clear-headed appraisals that Scott’s U.K.-based co-producer, Rob Ellis, has in mind when he declares, during a separate video chat, that she has “a really good sense of artistic self-awareness.”

Early on, Scott reflects, “I had all of these really lofty ideas about what would attract the masses.” With her searching intellect, she dissected the bonds of family, religion, convention and propriety in her songwriting, and her performances could feel both audacious and invulnerable. “I was at a point in my life where I really did feel kind of like a floating spirit, seeing everything, experiencing nothing myself,” she says. “The music did kind of serve as armor at that time for me.”

Sprinter, the first album she made with Ellis and one that established her as part of a new generation of sharp indie-rock songwriters, was a squally, theatrical, guitar-driven production. She followed that with the industrial daring of Three Futures. “The idea was to keep it as stark as possible instrumentally, and make it quite cold,” explains Ellis. “There was no deliberate kind of beautifying, really.” Scott was the one imposing the potent vision. She went so far as to remove the cymbals from the drum kit, to keep their bright, metallic sounds off of the recording. On Silver Tongue, which she produced on her own, she made more solemn use of angular guitars and grinding synthesizers.

At a time when scores of pandemic-weary artists describe their new work as being inspired by a desire for catharsis or escape, Scott’s leanings have finally come closer to aligning with those of the masses. “I felt exactly the way that everybody else did, which was confused and worried and anxious about the future,” she recounts. “And so I started writing this album as a kind of way to dig myself out of the tunnel vision that can be created by doom scrolling.” She fixated on matters more immediate and life-giving, and wanted to aim her creative energies, as Ellis puts it, “up and out, rather than inward and down.” “I did that for myself first,” she says, “and then I guess I decided that if I could do that for myself, then maybe I could try and help other people to feel that way, too.”

As breezily as she characterizes that move in hindsight, Scott isn’t one to just let herself drift in a given direction or leave an impulse unexamined. “Yeah,” she allows, when I point that out, “it was a choice. I made a choice.”

The assignment: “Write classic songs”

She and Ellis, both producers on Thirstier along with Peter Miles, had lengthy discussions about how to proceed, and settled on an assignment. Ellis asked the artist to “sit down with a guitar and write classic songs,” an apparently simple directive that, in fact, required Scott to alter her relationship to songwriting. “That made her think about that writing process from the point-of-view of a songsmith,” he says.

Treating songwriting as a craft, and not only an art, wasn’t a foreign concept to Scott, who certainly listens to professionally polished earworms (lately ’80s country, she says) and studied commercial songwriting at a school, Belmont University, with a direct pipeline into the Nashville music industry, but she separated herself from all of that when she started making music as Torres. She was deliberate about this new writing process. “Any time I found myself doing something that didn’t feel like the intended path, I just redirected,” she says, “whereas previously making albums, I would be like, ‘OK, well, it’s writing itself.’ You know, ‘The song is dictating what it’s going to be.’ But I had to do a little more chiseling this time around.”

That focus carried over to the recording sessions last fall, where Scott’s hooks were accentuated by straightforward chord progressions, zippy synth lines and fat, fuzzy guitar tones. “The center was the melody in the song,” says Ellis, “and the atmospheric touches were adding to that feeling.” Those touches included pop harmonies, handclaps and tambourine, all categorized by Scott as “sounds that I would normally think are super cheesy.”

If she was going to engage with pop music’s techniques, tropes and gimmicks, she was going to do it with conceptual commitment, wresting certain gestures — especially those that seem to reinforce binary, heteronormative models of masculine or feminine expression — from their comfortably familiar uses, and bending them to her imaginative will. Long wary of pop’s obsession with being in love, she’d previously depicted arousal and attachment with arresting severity in her songs and videos. Even when she pondered romance on Silver Tongue, she did it with a sense of melancholy.

The lust (and high stakes) of monogamous love

Thirstier is Torres’ first real celebration of pleasure and heat, sexual and otherwise, an observation that I share just a few minutes into our interview. “I have a harder time talking about that aspect of it,” she says, after a thoughtful pause. “It’s more felt than seen, more felt than spoken.” But she’s not denying it: “Yeah, it’s hot. It’s real hot.”

She tells us a lot about her experience of pushing into this territory in the way she sings the line, “My nerves can’t tell the difference between pain and pleasure,” in the song “Hand in the Air.” The first syllable of “pleasure” is mushed, like she’s having a hard time getting the word out.

Scott has done a great deal of contending with her southern Baptist upbringing over the years in her song lyrics and interviews. Midway through our virtual conversation, I ask her whether she’s detected in her own outlook any lingering vestiges of mind-body dualism. “Those of us who were raised in a religious context and a really sort of restrictive ‘deny the body, ignore the body’ sort of setting, I feel like that it makes its way into the music no matter what,” she reasons. “And, of course, I’m always trying to deconstruct it and I’m always trying to shine a light on a different aspect of it. With Thirstier, I just decided that I would use it as an opportunity to celebrate more than I have on any other, to celebrate specifically the body and the pleasures of the flesh and the pleasures of…”

Just then her partner, visual artist Jenna Gribbon, returns from her studio. On screen, Gribbon breezes through the room and Scott turns, self-consciously, to acknowledge her presence: “Hi Baby. This is going to be on NPR.” All three of us laugh. Scott, now more warmed up, regains her composure, and continues articulating her sensual theology. “A lot of that is just me doubling down on how much I believe that the body and the mind and the spirit have to be completely aligned in order for extreme joy to be realized.”

Scott gave her album a name that echoes social media shorthand for showing off and shopping around, for indulging in lust with no strings attached. But in the title track of Thirstier, whose dynamics build like a power ballad, her object of desire is already within reach. “Baby, keep me in your fantasies,” she sings, stern in her desire. “Baby, keep your hands all over me / The more you look, the more you’ll see / As long as I’m around, I’ll be lookin’ for nerves to hit / The more of you I drink, the thirstier I get.”

“I’m applying the term to a committed, long-term monogamous relationship,” she says, “so, you know, this isn’t about an Instagram thirst trap; this is about the love of my life. So right there, it’s already very high stakes.”

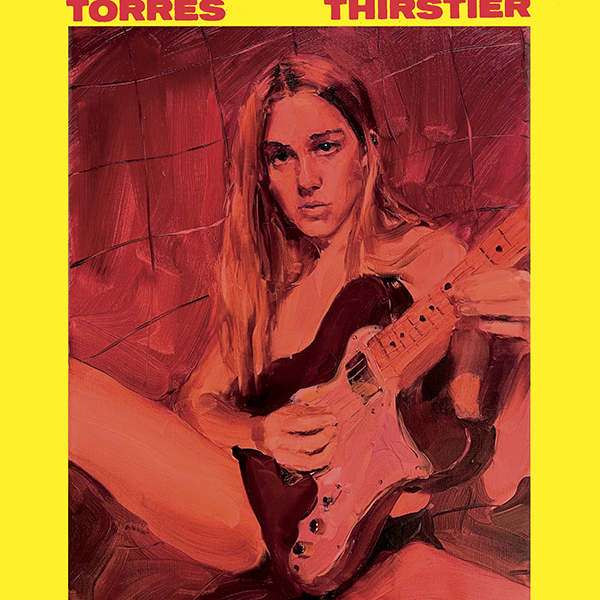

She’s talking about Gribbon, who painted the image of Scott that appears on the album cover, straight-faced with an electric guitar — the ultimate phallic rock symbol — between her legs. That’s exactly how Scott wants to be seen, staking her claim to macho exhibitionism when she pleases, just as she wants to be heard using terms of endearment that, throughout the popular tradition of “little darlin'” songs, have been the tools of men and boys occupying the role of serenading heartthrob. Torres, too, sings to her “baby,” her “darlin’,” her “girl,” although she prefers to tack an extra word on ahead of the latter — “lord, girl” — so that it becomes an exclamation marveling at its subject’s magnetism. “I just think it’s fun to kind of lay claim to these tropes that have been reserved for a long time for cis men,” Scott relates.

She’s got the range

The thing about the melodies and multi-layered vocal arrangements she’s shaped for this album is that they give her ample opportunity to flaunt her vocal range, to sing in a slight, fretful fashion, or be ceremonious, sweet, or reverent, or to revel in her resonant, full-bodied low notes. Her voice loses none of its power in that register; if anything, that’s where her vocals sound the most sensually insistent and insistently sensual. That’s where the action is. “It does feel like the deeper voice is what elicits the tingles,” Scott agrees.

Her range of expression is all the more fluid because of how deeply attuned she’s become to her own identity. She reflects, “Being someone who is nonbinary and has always felt that way, it’s always kind of like, ‘Which energy am I going to put out there right now?'”

“I really get to play as not just a writer,” she goes on, “but an actor and somebody who gets to embody all of these different voicings and characters on stage and on a recording.”

During the track “Drive Me,” she plays with multiple meanings of the word “drive,” deploying it as an invitation and a demand to a lover to get in the driver’s seat — unlike the countless car songs that aim to seduce a woman into being a passive passenger — and make the moves. What’s striking is that Scott does her most desperate pleading in a tenacious, bellowing vocal style. “I actually really questioned my approach to recording that song, because it is so growly and so commanding,” she admits. “I almost re-recorded it, but I went with that original version. I just feel like that’s how it has to be done, like I’m in control.”

Mackenzie Scott gets a charge out of these will maneuvers, and it is utterly thrilling to hear.

9(mda2nzqwotg1mdeyotc4nzi2mzjmnmzlza001))