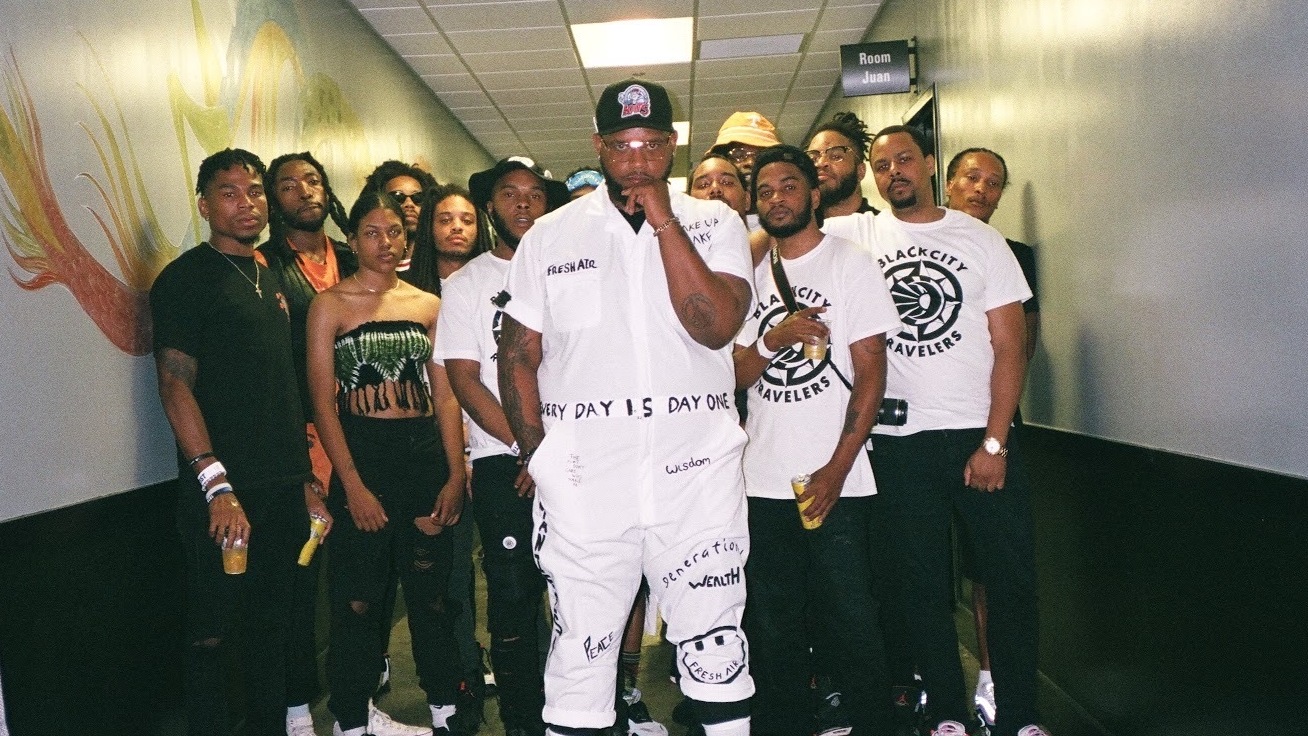

Entrepreneurial Mychael Carney helped his poet-rapper sibling, The BlackSon conceive of music as a business. Their BlackCity collective has grown into a model of community-minded and empowered economic self-sufficiency.

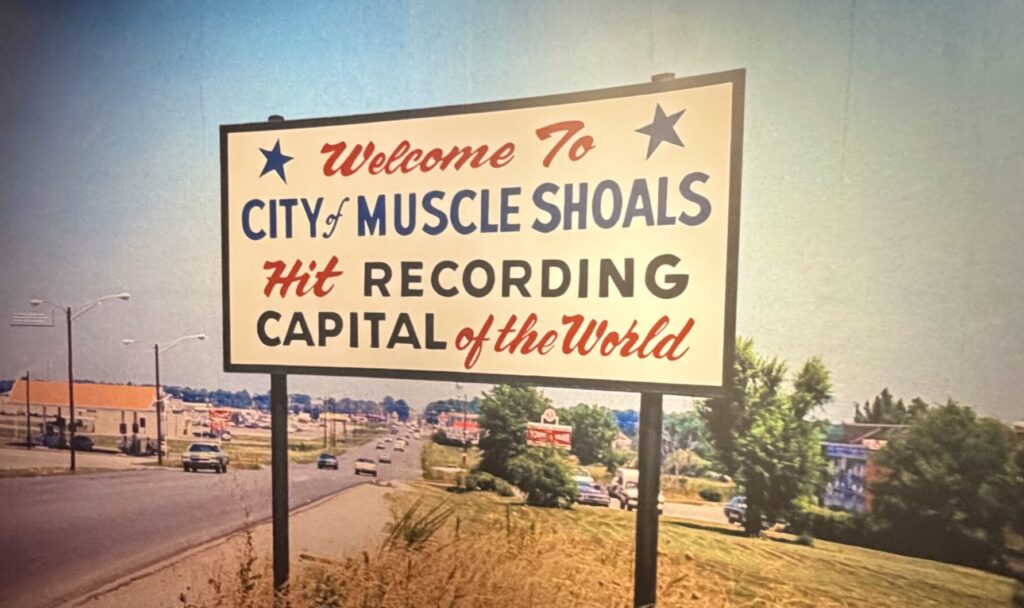

Rapper The BlackSon and his comrades in the BlackCity collective recognized that they’re operating in the shadow of the Nashville music industry’s consolidated resources, power and influence. So they chose to look elsewhere, searching for a business model more in line with what they’re about: self-sufficiency and the building up of a Black cultural community that’s been undermined in myriad ways.

The BlackSon, born Sean Smith, and a couple of his friends made the turn from spoken-word poetry to rap in their mid-teens; Smith’s older brother Mychael Carney took his sibling’s output seriously enough to build a home studio and help him get organized, setting up a limited liability company and helping to create branded BlackCity merch. “At the core of all of this is entrepreneurship,” Carney explains. “That was the seed that was planted early on.”

Smith mentions the mid-’80s, pioneering southern hip-hop outfit Rap-A-Lot Records and Roc-A-Fella, the self-started New York venture that catapulted Jay-Z, as templates they studied. But Carney points out that they’ve also treated BlackCity like a self-owned version of a pro sports organization in a small market. “A lot of the small teams complain about resources or whatever it is that makes it to where they can’t find proof-of-concept or continuity or success,” he elaborates with conviction. “But then you have these outliers, like the San Antonio Spurs. They don’t make excuses; they make it happen. They make it happen consistently.”

The BlackSon was already releasing projects by age 18, swiping at the city’s record of racial and economic inequality in tracks like 2014’s “Music City Militant.” In subsequent years, he’d write about the criminal justice system endangering the lives of his young, Black peers. “This reality is endless / ‘Cause there cases still pending on some n****s I grew up with / Usual suspects / As long as n****s dyin, CNN won’t make it public,” he enunciates with deadpan knowingness, over a boom-bap beat and whimsically crisp, jazzy samples of plucked strings and piano during 2016’s “Wiretaps.” Despite the political underpinnings and philosophical poise of his work, Smith doesn’t think of it as conscious hip-hop. “I like to use the word ‘aware,’ ” he clarifies, “just because ‘conscious’ has come with this connotation of seeming like or thinking you’re better, or this different class.”

Over the years, he and his brother have built up a crew bent on staying plugged into realities on the ground, including Carney’s former co-worker Justin Causey, who now serves as manager, and a number of like-minded producers and emcees, who’ve done more clear-eyed writing about life in Nashville than plenty of country songwriting pros trafficking in Music City mythology. In “A Cashville Story,” Brian Brown is sly about his disgust for the development driving Black residents out of their newly desirable Nashville neighborhoods: “Gentrified my side, wanna take us out? Sweep us under the rug? We too dirty, dirty for that / We left that stain; you stuck with us.” The Black Panther Party-referencing clip for Reaux Marquez’s “Pass Go,” a funky track with a militant, distorted hook, dramatizes the need to protect the threatened, Black corridor of Jefferson Street, an important area for the too-often-forgotten jazz and R&B chapters of Music City’s history.

BlackCity, which also includes co-manager Eric Drake and music-makers JosephFiend, D1ON and OGTHAGAWD, earned respect and good will in the Nashville hip-hop scene by putting on shows, then a festival, then, in 2019, a DIY version of a writing retreat held at the North Nashville home, headquarters and hangout they’ve dubbed “The Compound.” They set up additional recording rigs, provided split sheets (forms that co-writers fill out to specify how credit for their creations should be divvied up) and offered pillows and blankets to those who felt like crashing on the floor. “Anybody that’s in music or anything or in any way around it came to the house and was there for those three days,” says Causey, reeling off dozens of names of singers, rappers, producers and videographers from every corner and collective of Nashville’s hip-hop underground. “We sent out those invitations to a bunch of people and they just pulled up.”

It’s in the spirit of BlackCity to collaborate musically with peers and freely exchange professional knowledge and strategies. Beyond that, their operation seems a bit like a closed system; they can do a lot in-house, including sustain their core business with innovative side hustles, like Carney’s bicycle repair shop, housed in the carport, the sneaker design Causey sold to Nike last year, Marquez’s skill at furniture making and a new moving company. Smith says he’s open to the idea of licensing his songs, but he and the rest of his squad aren’t interested in ceding a big ownership stake to any outside entity. He half-jokingly points out that theirs is a “disruptive” plan. “I mean, the music industry has a lot to do with how much you’re sharing [of] what you’re making,” reasons Smith. “If people know that it’s not a lot they can get out of it, it doesn’t really make sense business-wise to invest or have a heavy interest. I mean, we’re definitely open to doing business, but we are very homegrown and we’re definitely looking to make it a family business before a lot of the other stuff.”

They’ve embraced Black economic empowerment as an ethical imperative, working for their rightful share of the “It city” prosperity that’s disproportionately benefited white businesses and residents in Nashville. Smith explains, “We have a little phrase: free power — the idea of a free power source and people being able to exist empowered and not over or under the power of anything else. We talking about Black Wall Street; we talking about Tulsa. When we talk about BlackCity, that’s what we’re saying, is it’s only right that we all just get the opportunity to build and create for ourselves, you know?”

Over the years, Smith has worked as a youth advocate with the literacy-aimed poetry nonprofit Southern Word and Salama Urban Ministries, and his concept of community isn’t limited to those in music. He was one of several performers, including Taylorr, Gent and Eastwood, who did rooftop sets in a Lovenoise-sponsored series of livestreams to benefit the nonprofit Gideon’s Army, whose post-tornado recovery aid in North Nashville and organizing efforts against aggressive policing many peers have joined. He also admires the way that a late hip-hop star stuck around and reinvested in his West Coast neighborhood.

“I think Nipsey Hussle kind of planted a seed and it’s going to lead us to understanding what it means to be accessible in the right ways,” he says. “That’s how I see it for myself. But I also have these conversations with a lot of artists in the city right now. They’re like, ‘I want to buy a little stretch outside where we grew up and get a studio and a little learning center, a multimedia center where people might make beats and come and play basketball or swim.’ The goal is to just kind of continue to improve the community, from our unique perspective.”