Silvana Estrada has been called many things. Cantante, cancionera, Mexicana, singer-songwriter, U.S. visa applicant, touring musician. And now she’s also publicly carrying the title of heartbroken — and healing.

The 24-year-old’s first full-length album Marchita, or “Withered” in English, gives away its subject matter in its title. It’s about love, both drying up and thriving, and comes from the recent withering of Estrada’s own first love.

Don’t be fooled by the fact that this is her first this-or-that, though. Estrada’s poetic lyrics are as wise as they are pretty. And when her writing is combined with her expert command of the many instruments heard throughout the album, the music demands the level of respect given to musicians on their tenth album and tenth heartbreak.

Perhaps this level of mastery comes as easy as Estrada makes it seem when a musical life is all you’ve ever known. Estrada’s parents are not only musicians themselves, but luthiers — as in, they literally make instruments for a living.

“Having the opportunity to see a musician trying their brand new instrument for the first time, I know it’s really specific, but it’s something that everybody needs to see. Like, to see a 50-something-year-old man just like a kid trying a violin or a viola,” Estrada says. “Growing up like that taught me that music is the tool that I use to find my place in this world.”

Still, she says it wasn’t until about seven years ago that she made the decision to dedicate her life to it this way.

“But, before that, I knew that music would be my way to be happy, even if I was – I don’t know — a doctor or something,” she laughs, adding that her career of choice at the time was really professional volleyball.

Thankfully, for all of us, she spiked that idea.

On the Record: A Q&A with Silvana Estrada

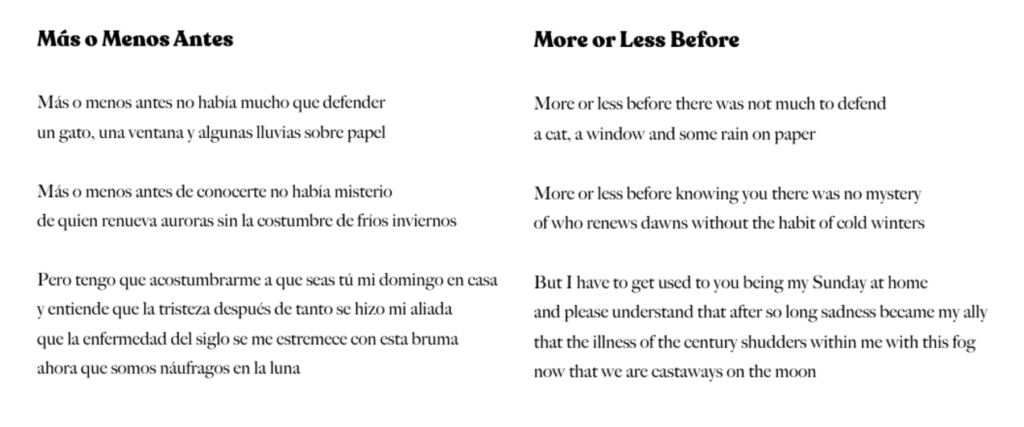

“Más o Menos Antes,” or “More or Less Before,” is a short, stripped back track that sets the tone of the entire album. “Marchita” starts there, so our conversation did as well.

Rachel Iacovone: I have to tell you, you had me at that first vibrato on “antes,” and there’s just something so warm and inviting about your delivery that feels almost like you mention a few lines later in that song, like a person being your “Sunday at home.” But in that same verse, you’re also, in that same warm tone, explaining to this person how “sadness had become your ally.” Is that why you chose this song to open — because I see pieces of both that love and sadness throughout the rest of the album?

Silvana Estrada: Yeah. Well, I love that you get to see that, because I don’t know if I did that on purpose. For me, it’s like a lullaby. I wanted to start with something really soft and really sweet. Because then, I feel like I get to really like dark places at some points of the album, so being at peace with my sadness, but also with my love or my loving, it was really important for me.

RI: That kind of up down in emotions, I know, is connected largely to love, like you’re saying, but I’m wondering if there is a message in there for America too. You were about to go on a U.S. tour when your working visa was denied by the immigration policies of the Trump administration at the time. How is it being in the states now with an album out about all these big, conflicting feelings?

SE: Well, it’s awesome that you bring that [up] because I’ve been like not talking about that a lot, and it’s so important, like I get to actually record this album because of that. And, you know, at that time, it was a really weird moment to be trying to have your papers here in the United States. It was like a Trump moment. And it was so hard. But at the same time, I feel so grateful in a way, because then I just stayed at Mexico City. This album, it’s also like an album of strength. Like, it’s about vulnerability, just to talk about the pain and the sadness and all those feelings that are normally bad feelings. You know, I just took all those feelings and put them in a beautiful space. And I guess I did the same when they denied my visa. I think I get to see the beauty of it. And right now, I feel so grateful because I’m finally here touring. I guess the message is just to try to defend what’s beautiful in life. That’s what I’ve been learning.

RI: I once asked my abuelita what her greatest regret was in life. And she told me that it was never learning how to play the cuatro, which, you know, is a traditional instrument for us in Puerto Rico, but also Venezuela. And you play the cuatro that your dad made you, right?

SE: Yeah, he made that cuatro for me. And you know, it’s so interesting that I play the cuatro because I’ve never been in Venezuela. I’m Mexicana. I’m from Veracruz. And at some point of my life, I was trying to make songs and I’d been playing the piano and the trumpet and even the violin for a long time, and I never get to actually feel, like, inspired. But I was really trying to find something where I can compose. I don’t know why, but I was really into that search. And suddenly, I just get into my dad’s studio, and there it was — the cuatro venezolano — just hanging there. That was, like, love at first sight, or first play. I don’t know how to say this, because it was immediately like I fell in love. It’s like a hug, the warmness of having the instrument just next to your chest and your belly, and the way the vibration moves, like, your soul. It’s inside you. Something moves when you’re playing the cuatro venezolano, and the sound is so folkloric that I loved the mix, because I feel the same way. I feel like me, like myself, I’m a mix of this modern but also folkloric sound. And yeah, I just fell in love.

RI: Well, this album is entirely in Spanish, but you translated all the lyrics to English as well. So tell me about how you approached that process. Why was it important to you to take this on yourself instead of letting everyone, like, use Google Translate?

SE: Well, you know, for me, these songs are poems, really. I use a lot of metaphors and it’s hard to translate that. And for me, it was really important to actually find like a poet who can, you know, translate the way I wanted to translate them to actually keep the meaning of the images that are in this album. So that’s why I talked with this amazing poet from Mexico, Mónica Mansour. And she’s bilingual poet, and she is a beautiful translator. We did it together, and it was so mind-blowing to see how hard it is actually to get the same ideas and the same images in another language. It’s so hard, and I’m really proud that I took the time of doing it, because I feel like it’s so important.

Some Q&A bonus tracks

A wise takeaway courtesy of post-breakup clarity

Rachel Iacovone: So, I know you’re asked a lot about the heartbreak that led to “Marchita” — but what I want to know is what you’d go back and tell yourself right after the breakup now that you have this album produced and out in the world. What insight would you share with the you back then?

Silvana Estrada: Well, oof. If I see myself in that position at that time, I guess I would say, “Just trust in your instincts. You know how to heal. You just need to be patient with yourself.” We all know how to heal. We just need to be more loving with ourselves to actually give space to that process. I guess that’s what I should… what I will say to me.

A work song, a love song

RI: I hear in your music, especially in this album, a lot of traditional folk or even native influences — like, I’m thinking about “Un Día Cualquiera” in particular. It means “A Day Like Any Other,” and the song has that heartbeat but also your vocalizing that reminds me of the kind of music you hear on the streets and in homes but isn’t always recorded in our culture. So, how did that — a love song — come together in such a way?

SE: Well, because it’s almost like a prayer for me, that song. It was really important to me to get the essence of that prayer. It’s also like a work song. And there’s this super beautiful music in Venezuela where women who are working with the wood, they are like ‘Pa, pa!’ and at the same time, they are singing. And those are work songs, but they talk about love in those songs. And it isn’t a little bit our life like that? Like, in the middle of all the work we’re doing — we’re so busy, and we’re so tired — we actually find space — I don’t know how, but we find space to fall in love. That song is actually a prayer — a hope of finally get the time and the calm to fall in love deeply and healthy and happily. That’s the whole point of that song.

A favorite child(ren)

RI: I know this is like asking you to choose your favorite child…

SE: Alright.

RI: But… do you have a favorite song on “Marchita”?

SE: Oh my god.

RI: I’m so sorry.

SE: No, don’t worry. Don’t be. You’re fine. “Casa” is definitely one of my favorites. I love that song. I really love it. And I’ve been playing it live, and every time, it’s such a trip because it’s so hard to get the arrangement, to have that arrangement and turn it into the live performance. So, every time we do it, like, definitely different, and we’re still, like, looking how to create that — all those sounds and all the whole idea of “Casa,” which is a really experimental kind of arrangement. Even the song is kind of this long poem about my parents, about my childhood, so I definitely love this song. And then the other one is “Ser De Ti.” You know, “Ser De Ti” is this song where I can finally allow me to be weak. You know, all this album is so powerful all the time, and singing and I’m defending all the tunes by myself. There’s just a few instruments. It’s all about the vocals. And this song is where I can finally just lay down for a moment and just enjoy the drums and the bass and the other people singing. It’s like a breath — like a final just sigh before ending the album.