About The Record

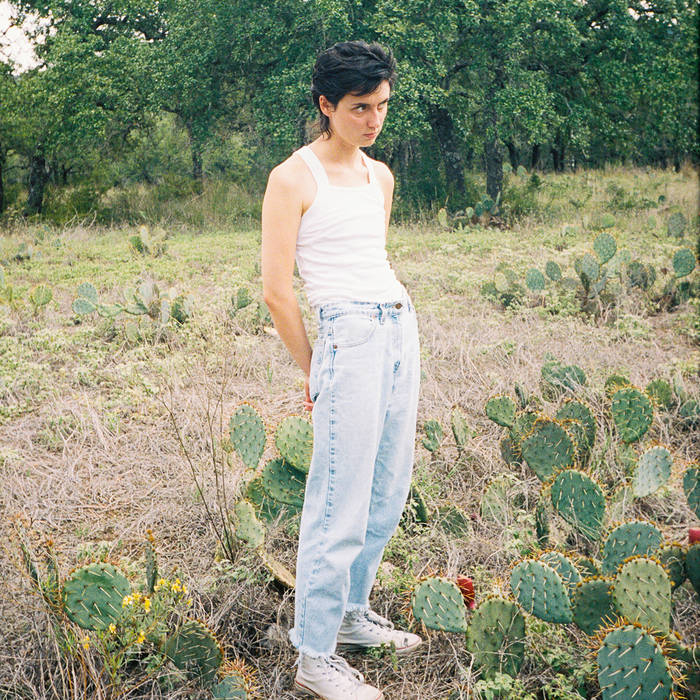

On her full-length debut Cool Dry Place, Texas-bred, Nashville-based indie rock singer-songwriter Katy Kirby explores topics like religion, family and self-doubt. The confessional record, years in the making, is the fruit of much self-exploration and soul-searching, which is evident in the vulnerability of the lyrics on tracks like “Eyelids” and “Secret Language.”

Kirby’s influences run from the classic (Leonard Cohen) to the contemporary (Big Thief). Her album feels like the work of a singer-songwriter with a distinct point-of-view, but it also has a frisky, full-band sound that was shaped in collaboration. Kirby tends to shy away from the expected singer-songwriter approach of stripped-down, solo strumming, preferring to enlist the help of her musician peers. She credits the textured arrangements of tracks like “Juniper” and, my personal favorite, “Peppermint” to engineer Alberto Sewald and producer Logan Chung.

Cool Dry Place finds Kirby experimenting and already showing maturity as a songwriter.

Artist: Katy Kirby

Project: Cool Dry Place

On the Record: Q&A with Katy Kirby

Emily Young: I read recently that you were recording with some friends in Alabama. Where are you calling from?

Katy Kirby: I am calling in from Fairhope, Alabama, home of Jimmy Buffett, fun fact. A friend’s parents have this enormous property with a house and a built-out barn that we have been using for the last couple of weeks to record a full-length album that I’m helping produce for my best friend, Joelton Mayfield, who I’ve known since high school. We all got tested multiple times and quarantined before we came here. All the people who worked on Cool Dry Place are here, because they’re also working on this record. So it’s honestly unbelievably magical.

EY: You spent a lot of time in Texas during the pandemic, right?

KK: Yeah, I was back home in the house I grew up in, after I lost a couple of day jobs in Nashville. I just moved back home with my parents for a few months, and I have been there since June.

EY: I did a similar thing for a while. What’s it been like returning home during all of this?

KK: It’s been weird; not as terrible as it could be. I mean, I love Nashville, but the things that I really love about Nashville are the people who live there. So, without being able to really see anyone or rehearse or record with people, it’s sort of all the same.

EY: I read that you grew up being homeschooled in a super religious environment. What has it been like returning to that setting?

KK: That’s a great question. It’s actually been shockingly OK. Obviously, I wasn’t psyched about any of that coming up when I moved home, and it doesn’t usually all that much. I have a really great relationship with my parents and the way they practice their faith is super open, and they’re just kind people. So it wasn’t scary in that sense, but weirdly this summer, in particular, it’s been really good to be hanging out with my mom and be able to talk to her about stuff even when I think she’s utterly wrong.

I think this was the first time that I was able to very directly be like, “I don’t believe in Jesus anymore,” and not have to couch it as a different expression of religion. Again, because they’re both very wonderful people, it was even less painful and awkward than I thought it would be.

EY: You speak to how you relate to religion now in songs like “Secret Language.” How did your parents respond to this record?

KK: My mother is very supportive and will read all the things [written about it]. I would have been so much more nervous to do these interviews about this record if I hadn’t had that conversation with them this summer.

EY: Telling your story to the world requires being vulnerable. Is it easier to tell that story musically than it is to tell those people who experienced some of these changes alongside you?

KK: It is a confessional album and it is a it does have a lot of intimate details and stuff in there, but a nice way to skirt around the vulnerability there is to make stuff up for half of the song and give myself permission to fictionalize however feels best for the song. So they don’t feel quite as diaristic and scary in that way. But you’re absolutely right. It’s much, much easier to talk to a stranger about painful stuff or sort of unsettled things inside you when they can’t dispute your memory.

EY: “Secret Language” is one of my favorite songs on the album. I’m a huge Leonard Cohen fan and his influence is obvious on that track. What is your connection to Cohen?

KK: To be completely honest with you, and this is probably kind of embarrassing to admit, but I wrote “Secret Language” so long ago that I just didn’t know a lot of music still at that point. While I was in college, I don’t think I could have actually told you that Leonard Cohen wrote “Hallelujah.” I don’t think I could have named you one of his songs. I think probably the Jeff Buckley version was just sort of rattling around in my head. I also remember in high school, some girl performing that song at a talent show or something, but it wasn’t like the actual version of the song. It was like a more Jesus version of the song, which was horrendous. They actually made it into a worship song.

So I wasn’t trying to connect with Leonard Cohen while I was writing that. But on the other hand, “Portals” was written right after someone that I was dating actually introduced me to a lot of [Cohen’s] stuff. So that was a song where I felt like I was trying to pull off some of the things that I felt like he could pull off. And it was really scary.

EY: What kind of music did you have access to as a kid?

KK: I didn’t hear any music from my parents, other than my dad likes barbershop quartets, and then the Christian Contemporary Music Industrial Complex and worship music. When I was probably 14 or 13, I started playing on my church’s worship team, and weirdly, the 30- or 40-year-old moms and dads who were also playing in that band started showing me stuff like Sufjan Stevens and King Crimson and The White Stripes. They were like, “Check out this cool stuff.”

EY: Was that when you started making music yourself?

KK: I started writing songs that I was proud of when I was, like, 16. I was trying to rip off a specific Rogue Wave song [from the album] Asleep at Heaven’s Gate, and literally just stole the chord progression and put a top line over it. I think that was a really interesting moment for indie rock, and I’m kind of glad that I became aware of stuff around then, because a lot of really interesting blends of genres got sort of handed to me on a silver platter through some very cool people that I knew.

EY: At what point did you decide that you wanted to pursue music as a career? Was that why you attended Belmont? I went there too, by the way.

KK: Yeah, that’s why I attended Belmont. I’ve always wanted to be a musician, but was never quite sure that I could pull it off. I did go because they had a songwriting major and I was like, “Well, I know I’d like to do that.” I switched out of that to an English major after first semester, partially because I was intimidated by a lot of people that I was in classes with. But I don’t think I was absolutely sure that I wanted to pursue music as a career until, like, 2018.

EY: How did you how did you find your musical circle? What was it like figuring out how to make an album with them?

KK: A lot of people that I started working with, Belmont is the main connection. But Joelton Mayfield, whose record I’m producing here, I’ve known him for eight years now. And we played in our school’s worship band and stuff. It’s people that I’ve always held very dear and have always wanted to play in my bands, because their projects are super cool. I just know them to be lovely people who also happen to shred.

EY: Your album feels like the work of a singer–songwriter with a distinct point of view, but it also sounds like it has been shaped by a band. What kind of stylistic exploring did you do individually and collectively with the folks that you recorded with?

KK: That’s a great question. The [tracks] really were shaped by them, and I think especially because a lot of those songs are so old that we had a chance to play them over and over and figure out what worked and what didn’t. A couple of songs like “Juniper” that are a bit older have been through a few different iterations of bands that I’ve had. I can’t possibly stress enough how many people’s brilliance went into making Cool Dry Place sound good and how much of it was not really me, especially Alberto Sewald and Logan Chung, who produced the record with me primarily. The two of them made it feel as good as it does and feel as rich as it does. I think without them it would have absolutely wound up in a much blander singer-songwriter fare, which I may have never released due to shame.

EY: Well, I feel like you’re kind of the focal point of the record, really.

KK: I mean, I wrote the songs and I sang them and then I’m doing interviews about it. But I’m so glad that they’re here, and I’m so glad that I’m going to be in the same place as most of the people who worked on it on the day it comes out. That is the greatest thing that will happen to me all year.

EY: It’s an interesting and challenging time to release a record and I mean, especially a debut. Typically, there’s all this preparation and promotion that leads up to it that has absolutely nothing to do with the recording process at all. How has that been for you?

KK: I’ve been really fortunate to be able to be in Nashville for short periods of time this year, despite COVID, but I haven’t been able to play live with anyone for a really long time. In fact, probably later today we’re all going to get together and play through the album real quick just to see how it feels. I’ve never released a record before, so I don’t know what I’m missing. But it would feel so incredible to be l gearing up to go on tour right now and to feel like I was on a team in that way. We’re doing the best we can.

EY: Do you feel like these folks in your little inner musical circle have helped you progress as an artist?

KK: Oh my god, yes. Joelton, as someone I’ve known for a really long time, is definitely that for me. Nick Johnston of The Pressure Kids, who are Nashville locals, is someone else I’ve known for a really long time and I’ve seen him grow up. Layne Rogers, who I also went to high school with, is here and they are someone who has been making me listen to cooler music since 2011, 2012. They made me listen to Grimes. So, it is really magical to be around people who have just made you cooler and you’ve seen grow.

EY: What are some of the current musical influences in your life?

KK: Quarantine and COVID kind of put me in a weird headspace in terms of listening to new music. I got really into pedal steel guitarist greats for a few months in the spring there. I really love the Lomelda record and I would definitely say that Hannah Read of Lomelda is such an influence in the way that she makes music and the way that she writes songs. It makes me feel like I have permission almost to try things that I really want to try. Another person who makes me feel that way is Buck Meek who I am label mates with. He’s the lead guitarist of Big Thief and just the most brilliant songwriter.

EY: I was actually going to ask you about Buck Meek, because I too am a fan, and I saw that you were on the same label.

KK: Oh, huge. His new record is so amazing, it’s ridiculous.

EY: Back to the specifics of Cool Dry Place, you do still have some very stripped–down tracks like “Eyelids.” What made you decide to stick with some minimal accompaniment for some songs?

KK: For “Eyelids,” I felt like the way the sentences in that song are constructed would be difficult to diagram as sentences if you wrote them out normally. I think my impulse there was to not overload it, so that the meaning of the song or the thought that I’m attempting to make whole is obscured by something too cool and awesome on guitar or whatever. I am a singer-songwriter and I do kind of feel self-conscious about it all, honestly, and that’s why I’m usually very allergic to acoustic guitars, but sometimes it just feels right. Even if I’m scared of being too girly for some reason, some songs just kind of demand that.

“Fireman” was one that I was so afraid of making it feel too soft or too folk-revival, so I took it in this really bizarre direction that we have buried somewhere where it’s way more electric guitars and vocal sounds really compressed.

EY: “Traffic” features this Auto–Tune-ish vocal sound that’s on the other end of the spectrum from a stripped–down acoustic sound, so what made you decide to go with that for that track?

KK: Originally, I was recording a demo for that with Logan Chung in his old house in Sylvan Park. I was working a customer service job on the phone and I talked all the time, and I had gotten a cold that winter. So I sang for the demo and I sounded so bad that I asked him to put an Auto-Tune filter over it, so I wouldn’t be like distracted by pitchy-ness. We left it on there for a while, and then it started to feel really right. I dug my heels in and insisted that we keep it, and I’m really glad we did.

EY: That’s not the answer I expected, but I appreciate it. That brings me to my final question too: In what ways do you hope listeners will connect to this album?

KK: Oh, gosh, there’s no way to answer that and not sound like a jerk. I mean, there’s a lot of things for albums to be to people. The type of record that I really like are ones that sort of unfold over a long time and maybe feel like second-listen records. That would feel really special if someone walked up to me and was like, “I didn’t like this at first and then I liked it later.” Or just the feeling that any of the songs on this record are durable in that way or still feel helpful to listen to a few years later.