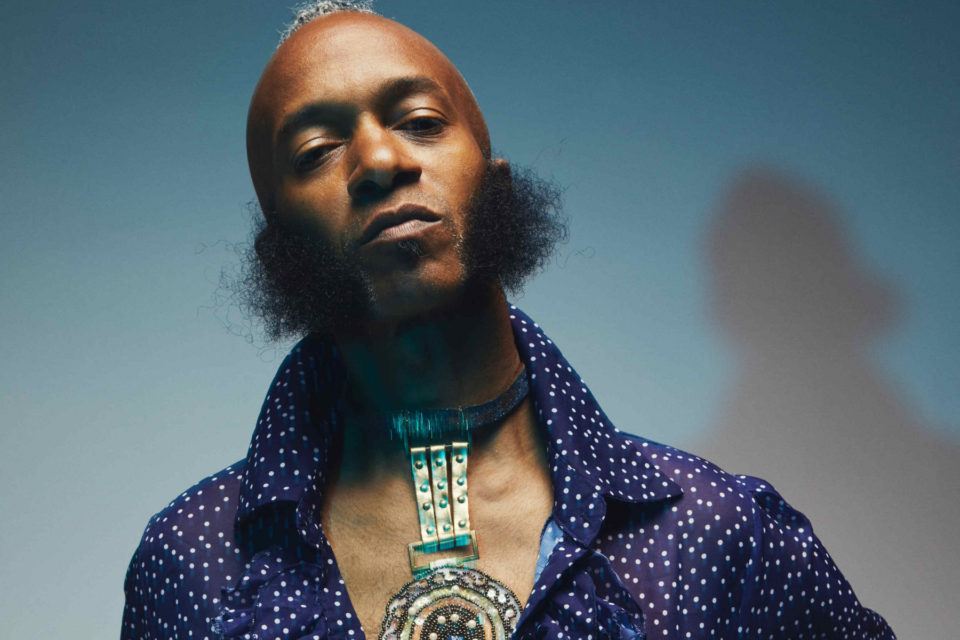

The story for Fantastic Negrito’s fourth album White Jesus Black Problems goes back roughly 270 years ago. Thanks to the pandemic, unchecked emails and the artists Sting and E-40, he discovered it.

After three Grammy award-winning projects, Xavier Dphrepaulezz, better known as Fantastic Negrito, began focusing on collaborations and duets. The last session he did before the pandemic was with Sting, opening the My Songs tour in 2019. After that, he invited fellow Oakland artist E-40 to contribute to a song on his third album Have You Lost Your Mind Yet? and performed some of his own songs in DC’s TV series “Black Lightning.”

Negrito had flown out to Georgia to work with E-40, but due to the pandemic, he was stuck in his hotel room. He began to play the guitar and got on his laptop. He says his emails looked a mess. Going through messages alone in his hotel for six hours, he stumbled across one whose sender claimed they are related, with a link attached. To his surprise, these people were related to him.

Negrito sits outside of the farm he calls Revolution Plantation as he describes what it was like going through all these records and discovering a story that would change his life.

“The first thing that shocked me was my father’s side,” Negrito says. “Everything my father told me about myself was untrue. Even my crazy last name, that’s all made up by my dad. My dad had another family that he never told us about. He had kids he never told us about. I’m sitting in that room and realizing my last name is not even real. I’m from the Bahamas, I’m Caribbean, I didn’t know that. That was shocking to me. So I thought White Jesus, Black Problems. Why did I think that? Because I thought my dad was born in 1905. He’s 33 years older than my mother. I thought 1905, that’s a generation removed from slavery.”

He described his father as a smart and progressive Black man, which, he says, was dangerous in 1905. He understood that his dad lied to people so he could be treated differently. That’s when he thought about the album title, White Jesus Black Problems.

“This idea of white supremacy and how do you challenge that,” Negrito says. “I think my dad challenged it by lying to us. So then I go to my mother’s side. I see these Black folks dress nice. I look at the year and I’m like, ‘Wait, this is the year of slavery in Virginia. How they dress this nice? This doesn’t make no sense.’ It’s amazing the information you can find on the internet. It says Register Free Negroes. Whoa. I looked around the room like, ‘Damn.’ So then it gave me an option to go to the fourth generation for African Americans. That’s often impossible, so I was shocked by a fourth generation married couple. Register Free Negroes. Whoa. fifth generation, six generation. Now I’m tripping. I’m like, ‘Oh, man’ and I started thinking like, ‘Oh man, if there’s reparations, I may not get all of them now [Laughs]. Because I got some free blood in here.’ It felt like I’ve gotten away with something. I don’t know if I like the feeling or dislike it.”

Surprised and also unaware of the amount of free Black people in the South during slavery, after discovering that he in fact comes from those people, he continued to go through to the seventh generation of his family.

He found a document that gave the name of Elizabeth Gallimore who was charged in Amelia County Court in 1759 with unlawfully cohabitating with a Negro slave belonging to Henry Jones and also for having several biracial children. So he contacted his his brother, who is a historian, to explain the document and learned that Gallimore was an indentured servant and her last name was most likely Scottish. He was inspired by the story, because despite Gallimore’s privilege in the 1750s, she chose to fall in love with a human being, a Black man that was enslaved, who Negrito called Grandfather Courage.

“I thought, ‘Wow, we could use some of this right now,'” Negrito says. “People freely making the decision to love one another from two different sides of the world, different sides of the spectrum, and doing it successfully in a sense that my Black ass is here, meaning you all got something done. I thought, ‘What an opportunity to tell a story of how an interracial couple in the 1700s challenged the edifice of white supremacy. I thought, that is f**king brilliant. Like, who’s going to hate this story? Because it’s basically Romeo and Juliet.’ So that’s how it got started and musically, I just stayed out of the way. I just let it do what it’s going to do and let it tell the story, and let it choose the music. I’m just a guest in this room. Let me get on this train and ride White Jesus Black Problems.”

Each song on this album is a chapter of Elizabeth Gallimore and Grandfather Courage’s story, with songs like “Highest Bidder” discussing how we live in an society where everything is for sale. “They Go Low” addresses the power of greed, while songs like “Man with No Name” and “Oh, Betty” discuss racial exhaustion. Interludes “Mayor of Wasteland” and “You Don’t Belong Here” give listeners the reminder that we still face some of the same issues today.

The music behind the story is bold and bombastic, as Negrito shares a love story about the challenges these two faced and how they found a way to be together in the end. (I hope I didn’t spoil the movie for you.)

“There are a lot of gifts within a tragedy,” Negrito says. “Within a hardship, there are many blessings. This is probably the most important work of my life. This changed how I view everything, how I view race, how I view white and Black, this whole construct of race. It could be the last record I make, I don’t know. It just felt like all I need to do is tell this story about how my seventh generation grandparents got something done. Hello, Congress. They got it done.”

On the Record: A Q&A with Fantastic Negrito:

Marquis Munson: How would you describe your upbringing growing up in Oakland?

Fantastic Negrito: I would describe it as the full spectrum. Incredibly, culturally, and spiritually rewarding. And then dangerous, violent, and challenging. But the duality of both of those worlds is extremely brilliant and innovative with a lot of culture movements sonically and visually and lots of heartbreak, danger and challenges. So the duality, which is often the case. I think people who are going through it often produce some of the most intriguing artform and culture.

MM: Growing up when did the idea to pursue music start for you?

FN: I feel like I’m still pursuing it [Laughs]. A couple of different things happened. I did this talent show and we’re doing this dance routine and I really liked the idea of people appreciating what you did on the stage. I’m the eighth of fourteen kids and I ran away when I was 12, I never saw my family again until I was an adult. So I had a lot of challenges in terms of filling that void of being the middle child of 14 kids and there isn’t enough attention and love to go around. So I think I tried to self-medicate by getting on stage. The neighborhood I was in we were all making wrong decisions and selling drugs, being involved in crime. A couple of my friends had been murdered around me and also my 14 year old brother died at the hands of gun violence. I made a conscious effort to do something different. So I started sneaking into the University of California, Berkeley to learn music. I would just sneak into their practice rooms and pretend I was student, and it worked. They gave me the key every time. I was always nervous like ‘They’re not going to give it to me.’ and they did. So that was my introduction to music, which was stealing it [Laughs].

MM: I was reading on Tidal five albums that changed your life and one of those artists was Prince and his album ‘Dirty Mind’ how did Prince inspire you?

FN: I think Prince for me was the black man that could be different and I can relate to that because I felt different. Once I seen a brother wearing garter belts and stuff, but had fine women, I was said ‘I can do that.’ I wouldn’t wear the garter belt, but I could go in that lane and just be extremely different and be yourself. He was a great teacher to a whole generation of kids. I was definitely feeling marginalized. I’m growing up in the hood but man I like these leopard skin cowboy boots and I got to wear them. I know they’re going to laugh but I got to [Laughs]. I think he helped validate that at a very young age. So I don’t know so much musically, as much as just his philosophy. He’s like some musical genius and I’m a musical amateur, I’m happy with one chord. So I think his philosophy was incredible. I think he came from a long line of African-Americans who had the audacity to be themselves. You can go back to Little Richard and Robert Johnson. These people who were really bold and that’s a part of the black experience. I feel like that’s our weapon of choice sometimes. We just got to be loud, we got to be bold, we got to be ourselves. And I appreciated that from them.

MM: So how would you describe your musical style to someone?

FN: Black roots music, simple. And then you got soul, funk, blues, foot stomps, handclaps, B3s, mini moogs, disco, hip hop, all those vibrations. To me all of that is Black roots music, rock and roll all that. So I really view the music that way. It’s not even my music, it’s just a garden like this garden I’m looking at now. This is planted long before we even came. I remember coming up with Fantastic Negrito and people were like ‘why man?’ I remember one of my white homies was like, ‘Man I got to tell you, that’s a bad choice. White people, we don’t like saying that word Negrito. It makes us uncomfortable.’ And I was like, ‘Wow, that’s good actually.’ I just thought if I picked that name every opportunity I could talk about Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Skip James, these people that maybe get forgotten. I think we’re just carrying on that legacy and the very proud legacy of black roots music. If you’re doing music in America, that’s what you’re doing. I don’t care if you’re a country artist, Sturgill Simpson, Kendrick Lamar, Eminem, or anybody. That music in America came from the black experience and I’m very proud of that. It doesn’t mean that you’re opposing anybody. Just means like, ‘hey, those are my roots.’ It’s just comes from a culture, comes from a experience. I think it’s amazing and I’m very fortunate just to be a conduit of this experience.

MM: I’m glad that you mentioned the creation of Fantastic Negrito because your first project was under your first name Xavier and you signed a deal with Interscope in the early nineties. A couple of years after releasing the album, ‘X Factor,’ you were in a near-fatal car accident that left you in a coma for three weeks. How did that moment change the way you make music?

FN: In my twenties, I just wanted to be famous, young, good looking, still kind of good looking [Laughs]. I wanted the cars, women, the house, the drugs, the bling. Living in that world in Los Angeles in the 90s. It took failure on that record, a complete fail. To go into a car accident and spend three weeks in a coma, lose your playing hand. It took getting smashed to get to this point as a middle age dude where I thought to myself I don’t want those things anymore. Now, I like to think of myself as a contributor and I think that’s why I’ve found value in the world. Value in the societies. Wanting a bunch of stuff that always ends up bad, let me tell you. In Buddhism that’s cause suffering. But I think when the Fantastic Negrito idea came about I was just like, ‘Man, I’m old, I’m black, I’m greasy, but I got some stories to tell.

Probably nobody cares but guess what? I don’t care either. I tell you as an artist, it’s something very powerful when you get to a point where you’re not caring about what that system wants, what that music industry wants. When you don’t care about people in power repressed fantasy of you. People have an image of the you when you walk room. ‘I think based on how you look, where you’re from, I need A, B and C from you. That way I can make a lot of money.’ I love artists that are just doing it and they’re not worried about how many likes or followers, or how many albums they sell. But it’s a matter of contributing something to the human family. That’s a beautiful part of creating. That’s what made hip hop so compelling because all of a sudden you have this demographic of people that didn’t really care about what you playing. They were going to make this music and sell it out of their trunk. That what’s so popular about punk music same thing. When people reach the point where they’re not worried about what you’re stressing. I’m in love with that movement always. That’s what attracts me to art, that visceral feeling of we can, we must, we will, no matter what. I love that and we need more of that.

MM: So going to go back to the project ‘Fantastic Negrito.’ After the release of that you won NPR’s Tiny Desk contest. How did that moment change your career?

FN: I was playing on the streets. I had an EP then I won Tiny Desk, to my surprise. After that, I made an album called The Last Days of Oakland after Tiny Desk. I live in a bubble. I live on a farm. I live in the trees. I think it has a lot to do with age, I practice gratitude and I’m always grateful but, just don’t be looking for nothing. I’m not looking for anything except for what my contribution on this earth can be and to help empower somebody else. I think that’s the true journey of a human being. That’s the secret in the sauce. You’re very grateful and then you just keep it moving because I’m grateful. Keep it moving, keep it beautiful, keep it real and keep it pure. I love that and that’s what the journey feels like.

MM: Speaking of that journey, have you had the time to reflect on those rough times from your upbringing to the car accident to see how far you’ve come?

FN: Yes that’s where gratitude comes. I feel like if I have a religion, it’s gratitude. You are just grateful for everything. I spent three weeks in a coma, I’m grateful for this [open and closes his hands]. Yeah, you all don’t know what that means to not be able to do that. So the rest is just extra. The gratitude starts in the morning. All of that is great and you celebrate it. When something good happens, I’m like, ‘Everybody, let’s eat, celebrate.’ Then we just move on and and it’s a new day the next day. But you got to celebrate the beautiful moments, wherever they are, Tiny Desk, Grammy, all that. ‘Hey, let’s get together. Let’s look at this trophy. All right? Now we’ve done put it away and let’s live our lives and go back into the studio and challenge ourselves and be inspired.’ That’s where the beauty is.

I don’t keep those Grammys on the shelf. I wrap them up and put them away because that can lead to craziness. I get together with family, friends, everybody that worked on it and put it away. It’s a beautiful way to live because then you can you’re free. I remember the first time I got a Grammy and I did put it on the shelf. I’d be playing and every time I look at it I would day ‘Is this a Grammy chord? Oh, my God, am I writing a Grammy Award winning lyrics?’ This is leading to some idolatry. So you got to love and appreciate it, but put it away and go and be like Kendrick Lamar. Go try to make something great that’s compelling, that’s interesting, that shakes the boots and these people. In my twenties, I would have fell into that trap. But in my fifties, its beautiful and celebrate it and then its like, ‘Hey, let’s move on, man. I think I better go clean that chicken coop.’ That’s all I think, like, ‘Hey, let’s take care of the farm and take a walk.

MM: So as you process the story for White Jesus Black Problems and determine you were going to put this story to music, what was the writing process for this album like for you?

FN: I just stayed out of the way. I probably did like 50 or 60 songs and I just stayed out of the way. If it’s not telling the story of Elizabeth Gallimore and Grandfather Courage, I gave the name Courage because they say unnamed Negro slave. I’m like, ‘Hell no that’s Grandfather Courage right there.’ So I just really stayed out of the way and I kept thinking that. Whatever this is, let it be what it’s going to be. I was surprised with the intro, I’m like, ‘what the hell.’ When I listen to songs like “Trudoo,” I’m laughing because I don’t really know what it is, but I believe in what it is. It was good to just let it do what it needed to do. I think that it needed to be courageous, bombastic, challenging, different, because that’s what the story was from the title to the choices of music. The only thing I did in production, I just made sure I kept steering it as far as it could go, the train. I was like, ‘What about we use the mini moog all over this album?’ I thought ‘Instead of using the B-3, Why don’t we use this 1971 transistor Yamaha organ that sounds light and kind of funny because it’s a love story.’ I made those choices. Other than that I was just letting it write itself, letting the story happen.

MM: The recording process for this album seemed different from your previous projects. It was just you and your drummer, James Small, before you adding the additional instruments. Was there a certain sound you were going after with that approach?

FN: The most uttered statement was, ‘Man, Let’s try it.’ I just kept saying that. I think the sound really had to be bold and it really had to be different and challenging. Each song was like a chapter of this story, and it had to be different. I had to stick to the storyline, which is two courageous human beings who had the audacity and the courage to be human beings. To do the thing that is most basic to us, which is love, which is pretty amazing.

MM: This album grapples with so many issues from capitalism, racism, greed, and towards the end of the album freedom. Even though these stories take place over 200 years ago, you still tie them into the present day with the language of the interludes Mayor of Wasteland and You Don’t Belong Here. Did you add those as a reminder to listeners that we still go through these issues today?

FN: Yeah, I thought they were all connected to me. It was easy as well. I still see the remnants of that. You don’t belong here, that’s exactly what they were telling my grandparents. ‘Hold up, this love thing, yeah y’all don’t belong here. This man is not a human being. He doesn’t belong here. You’re an indentured servant like you don’t belong in the society with the rest of us.’ We’re still dealing with the same things. I love the Mayor of Wasteland. The concept is imagining my grandfather in the present day. Chanty towns of Oakland. I tried to interpret this idea that he would think, ‘Wow, this is what freedom is?’ I’m chained up, someone owed me and now we’re free. But now we live on the streets?’ I just thought that was ironic.

MM: So discussing the track “Highest Bidder,” you discuss the idea that everything is for sale. With “They Go Low” addressing greed. What part of Grandfather Courage story are you telling in each of those songs?

FN: When I did Highest Bidder, I was thinking they sold my grandfather like property and my grandmother, who was an indentured servant, wanted to come here and work for seven years. That just seems crazy to sell people, what a weird concept. But I thought the fact that they were able to live although they had this illegal, forbidden union. I thought maybe the owner of them was just looking at the money. Even he didn’t even believe in this false concept of white supremacy. He was just like, ‘Let me just get more money. Y’all going to have some kids and when you have these kids, they need to come work for me for seven years.’ Because it says the children are bound to apprentice. That meant they’re born indentured servants because the mother was not a slave, she was an indentured servant. I wanted to convey the message that, ‘Hey, let’s not get distracted by all this other stuff. Follow the money, y’all.’ Of course there is racism, but let’s not get so obsessed with it that we don’t realize that it can be a distraction to people are trying to make money off of your Black ass or your white ass. They’re trying to get their paper, man. Whether it’s now or whether it was then. I just thought, that’s amazing gas goes up to seven bucks and we don’t do anything. There’s something about that. So I just thought again that’s the story of humanity. Everything goes to the highest bidder, people with the most money run the show.

MM: So does is it the opposite with They Go Low diving deep into greed?

FN: Yes, exactly. You’re very good with this man. These are just chapters. It’s like Venomous Dogma was like, ‘Oh, shit. No more freedom. Oh, everything is for sell, oh my God, this is the lowest a human being can go to sell another person for their personal gain. So they can have a bigger house, better horses, people serve them food, more stuff, give me more stuff.’ Those people that perpetrated that crime were the original gangster rapper. That’s all plantation owners were about. The same concept of being obsessed with materialism.

MM: On the song “Man with No Name,” it seems like that’s where the frustration and the racial exhaustion really begins on this record.

FN: Yeah, ‘I feel like getting away, I feel like running away. Think about it every day.’ I think with any story there is different chapters in the peak and tension that was definitely the tension. I try to imagine myself being my grandfather and what he would have thought. There’s some of that even In “Oh, Betty.” He’s a human being that loves someone. She just looks different from him. He was terribly frustrated in that song. Maybe it was kind of more tender and delicate. But yes, you’re right.

MM: What do you want the overall takeaway to be when people listen to this story?

FN: My intention was to tell a beautiful love story that was extremely powerful and that was wrought with challenges. Challenges insurmountable that we could never even imagine. But still, we achieved the high ground and love can defeat all the evil, horrible things in this world. That’s what inspired me. I’m kind of a weepy old guy now with little children. So I hope to be an optimist and tell a beautiful love story. But tell the truth now. You got to tell the truth. It may not be the kind of love story people are accustomed to. But maybe it’s probably bad to be married to me because I’m probably not that romantic. But I like shit to be real, man. Because that’s how you get to the next spot. That’s how you get to the next level by just embracing the truth, the sickness, the ills and the wrongs. Now we can get to love. I’m about putting out projects that are about healing, bringing folks together to the barbecue, to the cookout, that’s how it feels like to me. Like a town hall. ‘Come on, y’all. Let’s stop. We’re just going in circles and I’m sick of going in circles.’ So as an artist, I have the platform to maybe influence some of that, even if it’s in a small way, I want to do my part. So that was my intention. Whatever they take away, they do. But that’s my dream take on it.

MM: Listening to the album that was my biggest take away. But also thinking, how are you going to perform these songs in front of an audience?

FN: You didn’t hear it? It’s all completely nude [Laughs]. Everybody is nude with a birthday cake on it. I’m just messing with you. There’s some narrative when I perform now and I love that. My show I always call it a Church without the Religion. Grandma would say, ‘how dare you say that?’ But yeah, I feel like this is more narrative. I have something very real to talk about and in 30 seconds I can tell people the story about how my grandparents challenged this idea of complacency, racism, and bigotry. I love that. It’s like inheriting a million dollars. There’s a little bit of theater in this. There’s some video projection in this tour. I just did a show in Arizona, and there’s a lot of silence. When I talk about this, it’s amazing how quiet people get. There’s some real issues, I’ve got a song on there called You Better Have a Gun and that’s a part of the story. People have to think and connect that. Well, how did we get here? With obsession with power and guns. If you’re going over to get slaves, you better have guns, because they didn’t have guns. And now we have guns that kill our own citizens. So it’s a very American story. It’s funny, I play that one, man and people just look at me. They don’t clap at the end or nothing they are just looking at me. I always want to make music that makes people think, that’s my goal.

MM: You mentioned earlier writing 50 to 60 songs for this project. Movies and stories have sequels and part twos, so do you have a part two for this story coming out soon?

FN: I did record two alternative takes on this album. One is completely acoustic with brushes, everything slowed down and upright bass, and I’m calling that Black Jesus White Problems. Me and 20 year old cousin are doing a trap beat, electronic remix of the whole album. I’m having fun with it. You got to have fun with this thing. When you catch inspiration, it’s like lightning in a bottle. Artists don’t always get real, true, genuine inspiration. So we got that coming up and now I’m just working on building up my label with artists that I think are great. So a lot of those songs are going to those artists. This album is film and two remix albums.