Recently I jumped at the chance to talk to one of Britain’s undisputed “It” bands of the last couple of years, South London quartet Dry Cleaning, around the release of the group’s highly anticipated (and quickly fulfilled) second LP, Stumpwork.

Captivated as I am with lyricist and vocalist Florence Shaw’s wry, dry delivery — and had therefore drafted a few pointed questions about her observational songwriting, so core to the band’s distinct sound — I was a smidge disappointed she couldn’t join guitarist Tom Dowse and drummer Nick Buxton for the virtual chat with me from the 4AD office in London.

But this ultimately freed me, Tom and Nick to talk almost solely, and in nerdy, detailed terms, about Dry Cleaning’s music: the composition; the propulsion and the restraint; the diverse influences of the band members lending to the “quite interesting” mishmash of tones and rhythms; the editing process that is both highly disciplined and devoutly democratic, rooted in trust.

Stumpwork riffs, noodles, snares and sneers through sonic variations of the themes introduced on Dry Cleaning’s irresistible 2021 debut New Long Leg. But the new record also pushes for new answers to the riddle Tom posed: what happens when “you try and bring a metal band to play with a house drummer and a funk bassist and a spoken word poet…if everyone compromises a little bit”?

Listen to Stumpwork in full and read our jocular conversation (edited for length and clarity) below. You can also hear select tracks and artist insights all week long on WNXP.

On the Record: A Q&A With Dry Cleaning

Celia Gregory: Fellas, how are you doing? I loved New Long Leg so much and I’ve been really excited about the new record. I just got it yesterday, full disclosure, so it’s not been through multiple listens yet, but it’s extra fun to talk about it because it has some immediacy. First impressions.

Tom Dowse: Well maybe he’s a grower. [Laughs.]

CG: I’m excited to listen to it again, but want to talk to you about it first. Here on WNXP in Nashville I’m with some members of Dry Cleaning, they were here this summer and I hope you’ll come back soon. Can you introduce yourselves?

Nick Buxton: I’m Nick.

TD: And I’m Tom. I play the guitar in Dry Cleaning and Nick plays the drums.

CG: The new record is Stumpwork. Because you released your first record [New Long Leg] in still sort of the height of the pandemic. I’m curious about the difference in collaboration and pulling this record together versus the first one.

NB: Of course there are some differences. But we’ve been doing a lot of interviews and I’m regularly asked to cast my mind back to the New Long Leg era, and I can’t remember much about it. I mean, it was a very unique period because of COVID, obviously. But that kind of bled into the writing of this record because when New Long Leg came out, we didn’t have a lot to do. We’d done all the press around the record. We couldn’t play live. So we just wrote another one. It’s kind of a continuation. Having said that, you kind of put what you’ve done already behind you. You just move on.

TD: Our music was already a bit emotionally fraught at times. It could be quite melancholy anyway, and sometimes it could be quite contemplative, reflective. So when the pandemic happened, it’s impossible to know if it changed it or not. I mean, I’m already quite anxious, you know?

CG: Yeah, so people accused you of making, like, pandemic-era music, and this is just how you are.

TD: It’s hard to know. We’d never written a record before, so that was new. And then with this one, we had never written a record in a pandemic. So these are both completely new experiences.

NB: There are some similarities logistically, recording in the same studio with the same people. But, mentally, it’s quite a different place. We have more confidence. I think even if you try and avoid reading your press and all that, you can’t help but to via osmosis feel that you absorb the kind of positivity around what you’re doing, that it has been well-received, and you can’t help but feel buffeted by that.

CG: I appreciate you saying that — that honesty of like, “Well, we could pretend like we’re just in it because we love it, but it’s really nice to be recognized for work that you’ve made.”

TD: Also, we had a lot of space. When the record first record came out, we did a month worth of interviews and press and then there was nothing. There’s not gigs booked, there was nothing on the schedule. So we went back to write. Not many bands get to release an album and go straight back to writing on their own with no one telling them to do anything.

CG: I do want to talk about the writing of these songs. You said maybe it has been influenced without even knowing by the pandemic, but you two, as far as writing the music and then Florence [Shaw] bringing lyrics, I’m curious about how that process normally works. Is there a sequence or do you just get together and then hash it out in studio when you can all be in the same room?

TD: When I hear Flo talk about a process, it’s pretty much the same as ours — it is certainly the same as mine. It’s almost like you’re just collecting scraps of things, like a little melody or a chord you like. Or maybe you’ve heard another band, you think “That’s interesting.” It makes you think about something else, and you start collecting all that stuff all the time, and then you mix that with things that you’re doing. Like you pay the bills, you’ve got those vet bills for your dog, you haven’t seen your parents in ages… And just normal life, you know? It’s nothing particularly mystical. It’s just observing all the small details of normal life and then using the band as a way to get — like therapy or something, just put it into the band. You don’t have to think about it consciously. It just comes along. We just jam, improvise. There’s never any pressure. Or, there hasn’t been, there might be now. We just enjoy each other’s company. We spend a lot of time just chatting and eating, low pressure. .

NB: I often feel like those times are as productive as anything we do musically, they feed directly into the next thing you do. As soon as you go back to your instrument or whatever, it’s influenced by the chat you had before or the thing you were doing together before that. And in those little jams you assemble all of the things that you collect, all of the ideas. Then sometimes you might not have anything. And so you just kind of go with your feeling, with your instinct, what to do. Obviously sometimes we all have moments on songs where, say, the other three people have got something brilliant and you are struggling. I had that with “Gary Ashby.”

TD: That’s the challenge, really.

NB: Yeah, I was really struggling because I wanted to do something interesting and every time I was trying to do something interesting, I was just ruining the song. Sometimes you just have to do the simplest thing that doesn’t actually require any thought, you know?

CG: So “Gary Ashby” is an example that turned out where you’re like, “OK, let me not overthink this. Let me give it exactly what it needs on drums.”

TD: I do remember you struggling because it’s so simple. And you were like, “It can’t be this simple.” And every time you’d change it it would turn from like Hatful of Hollow -era Smiths, into Mars Volta. There’s a challenge for the drums because, I don’t know, it’s so propulsive.

NB: We tried so many different things. And it’s funny because I’m not averse at all to doing the simplest possible thing. Often that’s like my M.O. But for some reason with this, I thought that there was something more interesting there, and there just wasn’t.

TD: It’s hard when that happens, when things don’t go your way and you really believed in them. For a long time, “Hot Penny Day” wasn’t really a bit of a favorite among the others, but I loved it straight away. I kind of felt there was some different flavor and then it was exciting and I thought it’s like a flag, where we can go in a different direction later and try something else. All we had at the start of that was the [mimics riff] in the middle. Me and Lewis were vibing on it, trying to make it sound like [the band] Sleep…really dirty. But it didn’t work that way. Then he started doing the wah-bass bit and it sounded like a ’70s cop show.

I totally respected the others, they didn’t want it on the record and they were really upset about that. They felt like they were letting me down because they knew how much I loved it. Like, they didn’t they didn’t bend under the pressure and it made me sort of more sympathetic. And then slowly over time everyone came around to it. And now, Lewis, it’s one of his favorites and before he was like “Nah, don’t like it.”

CG: Well, you don’t sound difficult to work with. It seems like fun.

TD: At the end of the day we’re all just human beings, nobody is trying to make it shit. You know, they do what they believe.

NB: It’s a collaboration. So its as much about compromise as about anything else.

TD: We do things democratically, which is sometimes difficult as [a group of] four, because it’s two and two, which is why working with a producer like John Parish is handy.

CG: So you get the tiebreaker.

TD: Yeah. And you just get used to it not going your way. You get some, you lose some.

NB: I think that’s what makes the music interesting a lot of the time. If we were just four people, all had the same idea and there was never any kind of juxtaposition or rubbing against another idea it would be boring. Or maybe it would be brilliant, who knows? [Laughs] But I think that’s partly what makes Dry Cleaning interesting.

CG: No, I would agree. Are you two big on gear? I’m thinking about guitars specifically now, like tone and futzing around with pedals and stuff. Explain the process for you when you’re composing.

TD: I think when I’m playing, it’s like I’ve found a scuzzy tone that’s quite trashy in a way, like it sounds quite cheap. That’s my sense of humor. And it means that when you actually do some quite emotional things like [New Long Leg track] “Her Hippo,” it still sounds trashy, like a B-movie or something. My love of science fiction stuff is really in that as well — science fiction literature and film and stuff that’s in that sort of trashy, chorus-y sound, you know.

But the great thing about being in a band is with a rhythm section and a vocalist like that, I get so much space to do whatever I want, really. Like melodies, solos. I can do riffs and it’s like, like Lewis always finds a killer bass line in everything he likes. His hit rate is amazing. He comes from a totally different vibe. He’s more into funk and got raised on house music and disco and stuff like that. And then like working with Nick, he’s just like the timing metronome. I’m usually trying to urge forwards. I’m excited and Nick’s a bit more reserved in the back of the beat sort of thing. And when it actually merges and you all get on the same page, it’s really, really exciting. It’s my job to calm down.

CG: Nick, when you’re drumming, are you thinking, “How is Florence going to deliver this?” Are you thinking about her timing and cadence? I feel like I’m getting really technical at this point but I’m so glad to talk about it.

NB: It’s interesting to think about. A lot of the time we rehearse in these scuzzy little rooms and it’s quite hard to get the the actual vocal loud enough to hear exactly what she’s saying without it screaming feedback. So a lot of the time we rehearse, maybe we’ll try and play a little bit quieter or it may end up that you actually can’t really hear the words, but you can hear the rhythms. A lot of what Florence does is timing and rhythm specific. And it took me a little while to realize how precise she was being with it all — she doesn’t count in her head, she just manages to do it. So I’m starting to understand that there is quite a lot at work there in between the rhythms of the various things, particularly between the vocal and the drums.

CG: You mentioned a democratic process, but also that you come from different backgrounds. So when you are touring and you’re spending more time in enclosed spaces, I assume, do you guys listen to music together? How do you continue to be inspired by each other’s tastes?

TD: Well, so I don’t share my music out loud very much. It’s quite aggressive. It’s like a lot of metal and stuff like that. But Nick is very good at mixing it up. He always puts on a really good mix of things.

CG: Nick, are you the best DJ?

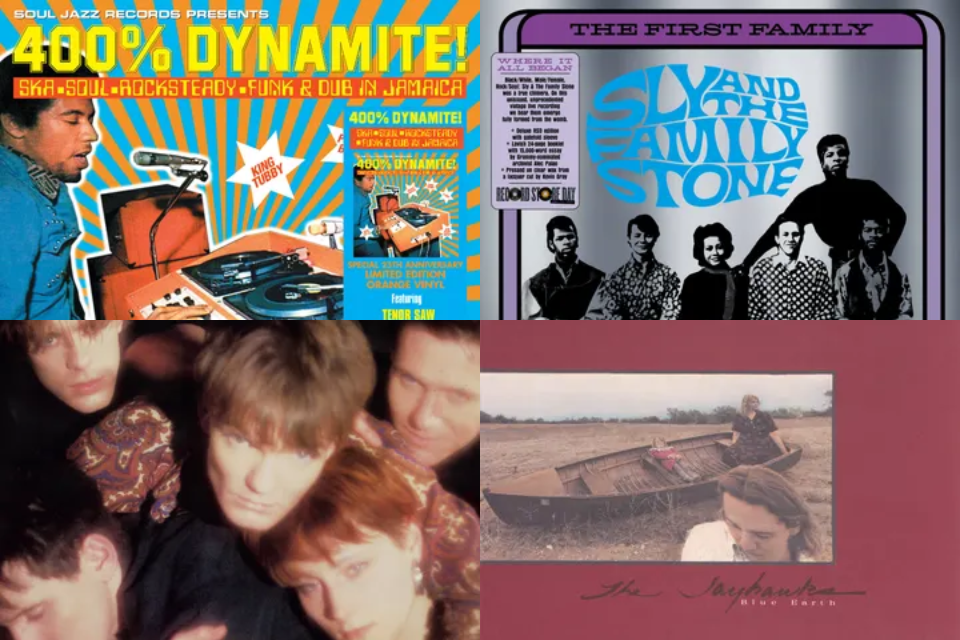

NB: I think the times where we’ve had projects where we’ve had to do radio shows or curate music for something, even just doing our own playlists for the pre-show stuff that we play at our shows, is always really great because when you say everyone gets to select ten songs or something, you really see people put a lot of effort into choosing something they think is going to work really well for a specific thing, and they want to put music on that they really love. It’s often what they’re listening to at that time, and I’m always very interested in what everyone else has to pick. I think that’s really important. I think you have to respect everyone else’s tastes. Like if you didn’t, what’s the point of being in a band together?

TD: Sharing music makes it easier to understand where people are coming from when they’re playing with you. Because Nick’s really into like things like Belgian New Beat, Detroit house and stuff like that — I really like the music, it’s just not what I gravitate to. So when he does it and I understand where he’s coming from, it’s not like you can say, “Can you do it more like At The Drive-In?” That’s not going to happen. So you try and bring a metal band to play with a house drummer and a funk bassist and a spoken word poet. If everyone compromises a little bit, you end up with something quite interesting.

When I first started, I would crank on the distortion and Nick was like, ” Do you always have to do that?” And I was really offended, like, “Fuck you.” I didn’t say that, but I thought, “Fuck you.” [Both laugh.] But I stopped doing it and he was right.

CG: I think about some of your songs that are compact and perfect just exactly as they are, like two minutes long. But I hear you as a band that I can imagine jamming and extending something for six, eight, 10 minutes. Is that what you do when you’re when you’re rehearsing?

TD: Most of the songs are start probably more like ten-minute songs, you know, really long. And then we just cut the hell out of it.

CG: Give me those demos.

TD: They’re my favorite things! I remember when I was still teaching, I’d get a playlist from Nick in the morning ‘cause he’s really good at taking the recordings from our rehearsals. And you would listen to it on the way to work, and a lot of the time it would be like, “I hate it, what a waste of time.” And then you go to practice and Nick would be like, “Oh, listen to this song. It’s the one you hated.” And he’s isolated a bit of it and you listen to it again and think, “Oh that’s quite good, actually.”

NB: There’s always something there, and then you extend that into a new song. There’s a song called “Liberty Log” on the new album that was essentially one of those jams that we didn’t cut down, we just left it. And it’s a longer tune, kind of similar with “No Decent Shoes for Rain.” You just haven’t edited them to that extent because they do exist nicely in the longer format. And that’s what’s great about making albums is that, if you really want, you can just have every song on your album be 10 minutes long – get really excited, do some really fun stuff, have some really long jams. But the editing process is really fun as well! And also it’s a test. You really have to be stern on yourself and be focused and be like, “Am I bored of listening to this now?”

CG: I just love you describing the art of addition but also subtraction.

NB: It is a lot of editing that goes on.

TD: But when a band is good at playing together, they start to welcome it. When we write and I really want to do something, if the others don’t want to, I trust them sometimes more than me.

NB: Yeah, it’s the trust. I mean, “less is more” is definitely one of the starting principles of the band. And I think we’ve come from a lot more minimal to a lot more going on, but it’s still a principle we stand by. But you have good ideas to start with to make that principle work.

TD: You know, we also used to teach stuff like that to our illustration students. We would be very keen for them to try to get into this mindset that creating and judging are two completely separate things. You shouldn’t mix them. So it’s like if you’re drawing something and you’re thinking, “This is shit, I can’t draw, this shit is never going to be good.” Just don’t think about it at all and just try and enjoy it…or just do it, basically. And then maybe the day after or a week later, you can see if it was any good. When you’re drawing something or you’re playing music jamming, you have to go with it to see what’s there.

CG: You want to turn the critical the critical part of your brain off and come back as the editor. But you need to just create to create?

TD: Yeah. Just get it out.