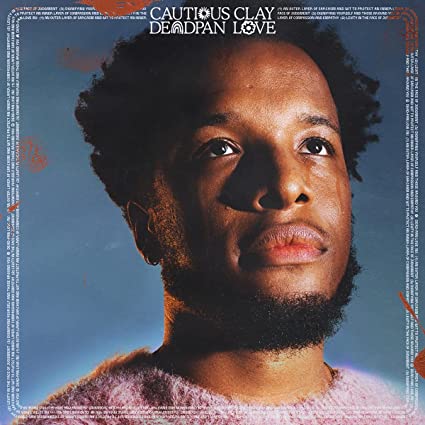

Project: Deadpan Love

Once Cautious Clay named Peter Gabriel as an influence during our interview, I couldn’t unhear the British art pop icon’s impressions all over Deadpan Love. Completed when he was in a self-described “yacht rock” and “80s soft rock” phase, Clay’s debut full-length record — which reached thirsty fans after three years of trickled-out single and EP releases — merges the sounds of his youth with modern innovations in production.

Although Clay has been primarily a beatmaker and producer to other artists in the past, and has been singing for just a few years, the soul of Deadpan Love is his vocals, which alternate between a breathy delivery and a honeyed falsetto and hearken back to reference points ranging from Genesis to Earth, Wind & Fire, Joni Mitchell and the sensual side of ’90s R&B.

Clay, born Joshua Karpeh in Cleveland and now based in Brooklyn after spending his college years in D.C., has grown his voice to supplement his early classical training on saxophone and flute. He incorporates those instruments tastefully on “Strange Love,” featuring Chicago rapper SABA and a sultry sax solo, and “Artificial Irrelevance,” where he uses sax to call-and-response effect.

The track that follows, “Whoa,” pushes a jazzy piano riff and hand claps through a soaring chorus that articulates the sensation of “feeling fake and underwhelmed,” trying to escape social pressure. During the bridge, Clay succinctly opts to “take five, because I don’t want to be here if I don’t need to.” In a newly reengaged yet nerve-wracking, post-quarantine summer, is there anything more relatable?

Deadpan Love is an album largely about image and those who either bolster Clay’s truest expression of self or detract and distract from it. The Cautious Clay moniker refers not only to the birth name of boxing great Muhammad Ali, but to Clay’s careful, if a smidge anxious, approach to connection. For the 28-year-old who never really saw himself as a public-facing “artist” until he indisputably was, catharsis comes through song. “I’ve had difficulty expressing myself, to people that I know, even,” he told me. It’s in his song lyrics that Clay can say what he means to say.

In the single “Karma and Friends,” with its shimmering string arrangements, he takes aim at transactional types, singing with side-eye, “I know what you’re after.” A hip-hop-style drum groove that Clay described as “dusty” adds grit to the otherwise smooth ballad “Roots,” which depicts a toxic relationship more easily prolonged than ended. During “Agreeable,” a single that first appeared on 2020’s Wildfire EP, he sings, “If you’re taking my side, I don’t want to know why.” The album closer “Bump Stock” recalls the spacey, ambient echoes of Bon Iver, and expresses the wish to be stripped of all feeling, because the high highs aren’t worth enduring the low lows.

This sentiment, like the one-word utterance “Whoa,” is a fitting response to what we’ve endured in the past year or so. Cautious Clay plans to tour the record with full instrumentation, having written the songs poised for their possibilities in lush, live performance. In these respects, the long-awaited Deadpan Love feels right on time.

On the Record: A Q&A With Cautious Clay

Celia Gregory: This is your first full-length record, even though you’ve been trickling out stuff for us for a while now, like EPs and singles. You have remained independent thus far, even with labels knocking at your door. What did that independence afford you to do as you created Deadpan Love?

Cautious Clay: It’s really definitely afforded me [the opportunity] to take my time with things and roll things out from the perspective that I’d want to do it, instead of feeling like I have to cater to or be a certain type of way to market myself. So when you’re seeing me literally doing anything, it’s just me. It’s definitely the way that I see it—everything from the videos to the artwork to obviously the production and everything. I’m overseeing it all, which is a ton of work, for sure. But I think it has paid off in the way that I am excited about this and I feel like it’s some of my best work. It’s definitely been a painstaking process getting it together, but it’s been certainly pretty rewarding, too.

CG: I can’t imagine doing every job from the artistry through figuring out how you’re going to promote it. That’s a lot. But you’ve been a producer for a long time, so that part you have in the bag. Are you a little choosier with it because it’s your debut LP?

CC: I definitely collaborated on this album more than I have done on any of my EPs or singles , mostly because I wanted it to have a super well-rounded sort of sound. I can produce on my ow, but I don’t genuinely think that that would have gotten the best results. I think if you’re looking at any of the best artists or best songwriters, it’s always good to be able to pick the people that you work with and be intentional. A lot of great producers on the album, Dan Nigro, Jim-E Stack, Tobias Jesso Jr., who’s a really good friend of mine over the past several years, I was able to utilize their skills in a way that felt like I could sort of oversee everything and then put it all together and make it what it ended up becoming.

CG: As far as influences go, I’ve read that you grew up in Cleveland, on your parents records’ like Earth, Wind & Fire plus “folky shit,” as you called it.

CC: Yeah, like Laura Nyro to Joni Mitchell, Nick Drake and Barry White and Marvin Gaye — every type of sonic palette. I felt very lucky and fortunate to have my parents be into tons of different types of music. No, I wasn’t initially super jazzed about it, but I obviously came back around to a lot of it. As any kid, you have a phase of listening to quote-unquote “bad” music. But I think it certainly shaped up to be OK.

CG: You mentioned you wanted this album to sound well-rounded, and your influences are certainly well-rounded. You got classical training on woodwinds as a kid too, right? In terms of what sounds you wanted to pull together for this album, could you talk about that process and narrowing ideas down?

CC: I’ve been through this kind of “yacht rock” phase, but then there’s also a lot of classic R&B that I love. I was looking to those references, obviously the Earth, Wind & Fire-like chord progressions. But then being really, really into Peter Gabriel and that kind of sound — ‘80s soft rock, mixing it in with current sounds. For example, there’s a song called “Roots” where I felt like I wanted to give it the aesthetic of a ballad. But then it has these really dusty drums that are sort of like hip-hop drums. So it feels like it’s ambiguous as to what you would call this song. I wanted these different influences, but then also write a good song along with it. The melody was like kind of where I could draw from in that context. But, yeah, I was very intentional with picking out what appealed to me in each song, and that was just an example.

CG: That song speaks to me. It kind of breaks my heart. I don’t know if it’s supposed to.

CC: It’s sort of about being in a toxic situation, in a relationship, and understanding that it’s toxic but not doing anything about it: “From atoms up to comets, life is never promised. But you could make me want to lie and be dishonest.” You could literally make me want to take the worst parts of myself and still run with it. From a sonic perspective, I wanted to make it groove, but also be, like you’re saying, a little more sensitive and emotional.

CG: There are a lot of songs on this record where you’re really candid about working on yourself. How has your ascension in the past few years, or maybe the expectations of this record, contributed to your overall self-image, your mental health? Because if you’re willing to talk about it in song, it seems like you’re pretty open about what it’s like to construct an image as an artist, but also maintain your sense of self.

CC: It’s been such a learning process, because I don’t think I was necessarily ready at first to be an artist. I didn’t know I was going to be an artist in this sort of public-facing way, and I don’t think that was what I even expected. But I fell into this situation. Who I am as a person, I feel like I like to express myself in a way where I can talk about scenarios that have happened to me or I highlight things that that are important to me. But I want to do it in a way that feels earnest and not like I’m preaching to people on how they should live their lives. I think about that even in the context of movies and TV: my favorite movies and TV cover really difficult things without feeling like, “That’s the lesson.”

I really just want to offer people sort of a sonic version of that, where can they can feel an emotion and then unpack that emotion, but not necessarily walk away and feel like, “Oh, my gosh, isn’t that such a sad song?” “Oh my gosh, isn’t that such an angry song?” I have always operated in the gray area. I think that’s where my music lies. It’s interesting to me, and I don’t think it’s always what people have the strongest reaction to, but I do think that it speaks to me and how I think the world is just super blurry. I can’t always have a perfect answer.

CG: Is it cathartic to write songs and to get them the way you want them?

CC: Music is that for me, I guess; it is my way of expressing myself. Even going back to why I’m [called] Cautious Clay: I’ve had difficulty expressing myself, to people that I know, even, like, the true feelings that I have. Music is that way cathartic for me because I can just really just say all of the things that I’m thinking,

CG: And you didn’t you didn’t really sing for a while, right, when you were an instrumentalist and working on beats?

CC: I guess senior year of college was when I started to sing, really. I was in this reggae band. I started to sing on record, when I was twenty-three. So about five years ago.

CG: You have a real purity to your voice that sounds like you’ve maybe honed it over years or actually grew up singing. That’s pretty cool to find in your twenties.

CC: Yeah, totally. I just started off because I was a producer. I was like, “OK, well, let me see if I can make my voice sound good on record.” And then it did. And then I was like, “OK, well, let me actually learn how to sing so I can play live and not sound crazy.” My voice has certainly gotten, I think, a lot better in person. I’m probably just hypercritical, but I think it was a catch-up process for me being an instrumentalist and a producer for so much longer before I was singing.

CG: The harmonies are what strikes me the most throughout this whole record. But it’s all you, right? It’s Cautious Clay plus Cautious Clay?

CC: Yeah, the harmonies are stacked.

CG: I’m thinking about how you developed as a musician: When you incorporate the flute, for instance, do you have sort of a spidey sense of, “This is where the flute needs to go,” or are you almost done with something and then you’re like, “This could use is flute?” It seems like you’re using these wind instruments sparingly on this album.

CC: Yeah, I don’t overuse them to the point where it feels kitschy, I guess. I don’t want that to be a thing, because I feel like as a producer you kind of are aware when it can sort of become a thing. I’m like, “Well, I do play flute, but I don’t want to be ‘the flute guy.’” So I’ll usually just play solos, you know, or it’ll be sort of a soft background kind of thing, like singing with saxophone. Putting on that producer hat and realizing, “This is a place that I can put it in.”

There are few songs on the album that have saxophone, but I was using it in a way where it almost felt like a classic jazz tune, sort of like there’s a voice that comes in and then there’s an instrument that comes in the middle part of the voice. It’s almost this conversation, a call-and-response element that I wanted to incorporate. It’s on a song called “Artificial Irrelevance” that I use that [style]. There’s not much else; the sax is like a voice.