Intro: Everybody’s been talking about how Beyoncé’s new album spotlights Black country and cowboy traditions. But even before she teased that project, author and songwriter Alice Randall had already announced her own book and album, both titled “My Black Country.”

Randall’s been lifting up foundational Black country voices for a lifetime, and senior music writer Jewly Hight reports she’s finally being treated as one herself.

Alice Randall: I’m excited about welcoming you into my apartment. This is actually a neighborhood that DeFord Bailey built, and people don’t think about that.

Jewly Hight: There are plenty of tour guides in Nashville that hit the standard high points of the city’s country music history. But Alice Randall will point out the Black predecessors missing from that narrative.

That includes harmonica virtuoso DeFord Bailey, who mightily boosted the popularity of the Grand Ole Opry when it was just a fledging radio show. The fortune it ultimately made funded at least one nearby mansion.

Randall’s small, second-floor walk-up was built in 1925, around the time Bailey’s radio career began.

AR: You can see the segregation that DeFord was dealing with in the very architecture of the place.

JH: She’s talking about the back door, the servants’ entrance.

AR: Do not trip over [that]. I’ll take you down these stairs for a moment. I go in and out a lot of my black door, honoring the Black women who, that’s the only way they could come in and out of my apartment.

JH: As a child in 1960s Detroit, Randall not only saw Black excellence up close at Motown. She learned to recognize it in country music too, while watching the Andy Griffith Show with her dad.

AR: The country music that was on that show, those were entries from my father telling me that jug band music was really Black, the banjo is really Black.

JH: Behind so many of country’s white pioneers were Black musicians whose influence had gone unacknowledged.

AR: But in the Black community, this was always known.

JH: So Randall arrived in Nashville four decades ago, with a lit degree and a mission.

Though she wasn’t a performer herself, she had success as a songwriter. But it was always white singers — the Forester Sisters, for instance — recording her Black feminist ballads. And that shaped how they were heard.

AR: When I imagined ‘Reckless Night,’ the first song I would have recorded, I imagined myself as that heroine.

“It’s a running out of luck town in old Virginia…”

AR: I was not assuming that they’re only going to think they’re white people in running-out-of-luck towns in old Virginia. So that part of the erasure I did not fully anticipate.

JH: Randall did score a number one with Trisha Yearwood in 1994, before leaving the music industry. Then she continued her solitary crusade in other ways — through publishing novels and teaching college courses on country music’s Black roots.

Through her poet daughter Caroline Randall Williams, she began to meet a new generation of Black women artists. Rhiannon Giddens, Rissi Palmer, Allison Russell and others. They’d begun unfurling their own visions for country music, and forging their own coalitions. Randall put them in her lectures. She put them in her new book, “My Black Country.” And now they’ve circled around her, reinterpreting her songs for her first album.

Producer Ebonie Smith listened to the old versions before consulting with the source, Randall herself.

Ebonie Smith: She contextualized all the lyrics for me in a way that the recordings really did not. So I had to do a little bit of unraveling.

JH: Smith fleshed out radically new arrangements, shifting many of the songs to minor keys that conveyed their true emotional stakes. Just listen to Adia Victoria’s wise and subversive reading of “Went For a Ride.”

JH: Being revered as a country elder is a whole different experience for Randall…

AR: These Black women geniuses riding to the rescue of my legacy, that is the ending of my story, and it is 100% triumphant.

JH: Not that Alice Randall has left the task entirely to them. She tells her own story, in exquisitely heroic fashion, in her book.

But you won’t find anything in there about Beyoncé realizing Randall’s longtime dream of seeing a Black woman atop Billboard’s country charts. That happened after she’d finished writing.

AR: It will be time for me to partially rest and be thankful. I would not be as thankful if I had not lived to see Beyoncé at the top of the charts.

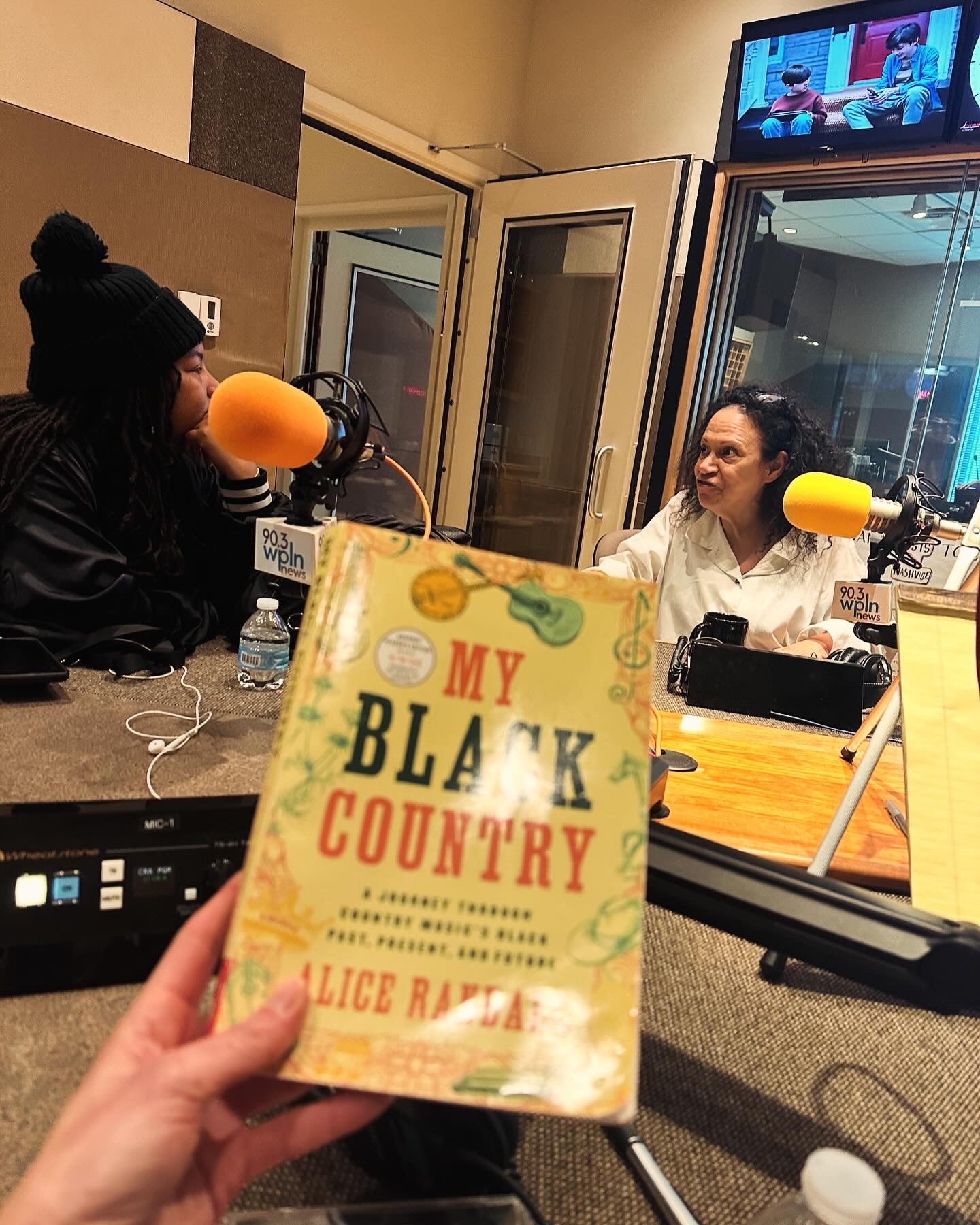

For Nashville Public Radio, I’m Jewly Hight.

Outro: And the track you’re hearing here is Caroline Randall Williams’ reimaging of her mother’s country number one, “XXXs and OOOs (An American Girl).”

For more on Alice Randall, watch for Hight’s forthcoming longform feature from NPR Music, and check out the This Is Nashville episode where Randall, the Black Opry’s Holly G and Marquia Thompson, granddaughter of Linda Martell, discussed Cowboy Carter and the multigenerational labor of Black women in country music.