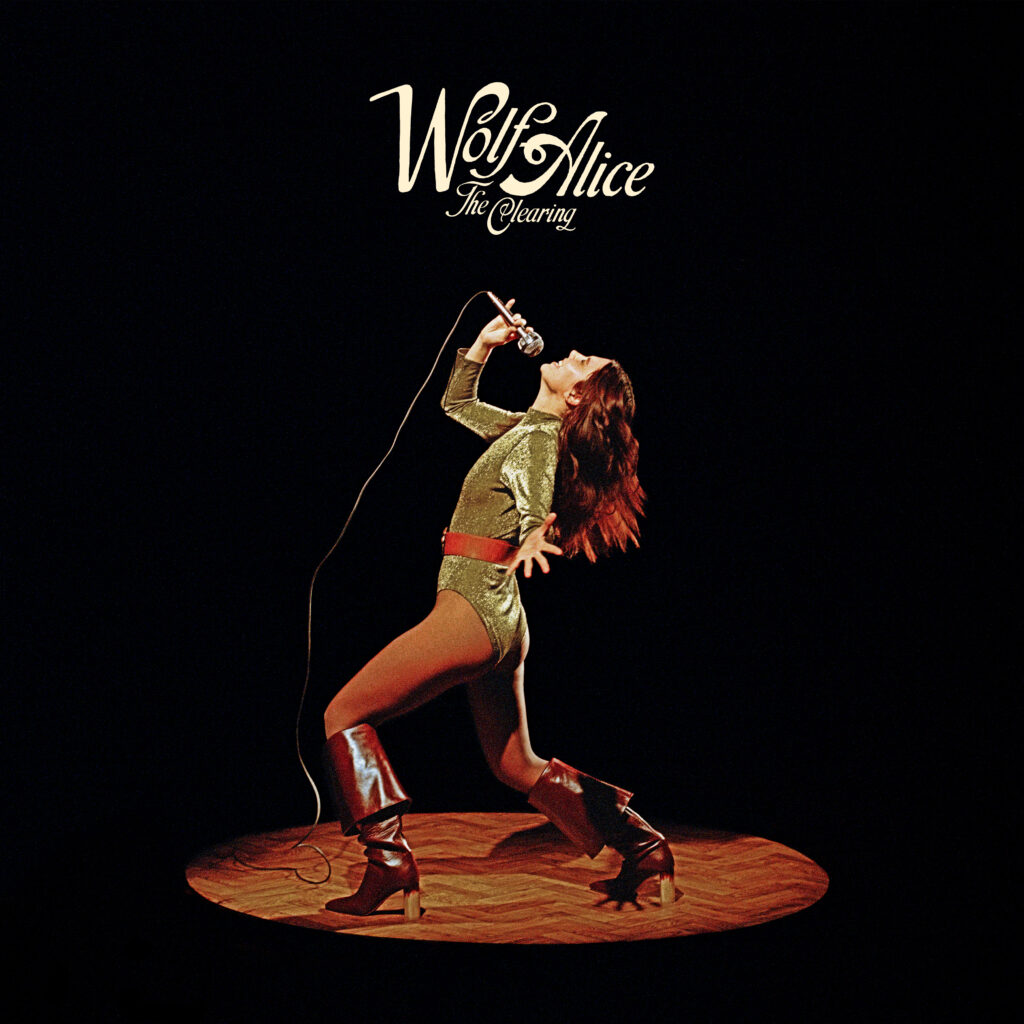

North London quartet Wolf Alice were fairly fatigued after a lengthy tour for their third album, 2021 release Blue Weekend, which was made during COVID-19 and therefore also took longer than usual to complete. What refreshed these songwriters and players after some time recovering turned out to be a more minimalist approach to, as well as a sense of positivity in, the construction of a song. “We were kind of eager to make music that didn’t make us feel depressed,” said lead singer Ellie Rowsell. “It felt like a challenge to write music that wasn’t dark.”

The band’s most scaled back production to date, a collection of classic (think 1970s) rock and pop-leaning tunes written mostly at home in the U.K. then recorded in Los Angeles, is The Clearing, which was released in August 2025. Amid the European leg of the Wolf Alice world tour, Rowsell and bandmate Joel Amey met me virtually to talk On The Record with WNXP.

“White Horses”

Ellie Rowsell: I’m Ellie, I sing in Wolf Alice.

Joel Amey: I’m Joel, and I play the drums in Wolf Alice.

Celia Gregory: And Joel, you also sing in Wolf Alice because one of the songs that we’ve played a ton of is the one that you wrote for the record. I guess we could start there. Can you talk about “White Horses”? ‘Cause I feel like towards the end of the LP, it is this sonic journey in and of itself. And so when I learned it was you, I was like, “Oh, that makes a lot of sense, [given] the movement of the song, [that it] is the drummer’s song.” Can you share a little bit about that one?

JA: Well, yeah, all of us wrote that song. That’s a true collaboration moment between the four of us. I had a demo that included a few of those sections, like the verse and I think maybe the chorus, and then brought it to the guys and we just had loads of fun sort of hashing it out and bringing it to life. So that was its journey, really. It was towards the end of when we were still in London. We’d been doing a lot of writing in North London, Seven Sisters, and I live in a different part of the UK, in a town called Hastings. I remember going home and just being really inspired by all these songs Ellie had brought in and the acoustic guitars that Joff [Oddie] was doing and, yeah, I kind of thought about those elements maybe from a drummer’s perspective, as you’re saying. Like I thought about the krautrock kind of beat and the groove and then all together we just built it from that.

CG: Thematically, was it sort of you reaching back into your family a little bit? What did you explore lyrically on that?

JA: Family, chosen family, very much of which the three people in Wolf Alice are to me. And yeah, just like in the interim of [2021 LP] Blue Weekend and this record, just some self-discovery about where my family comes from, geographically and also just like emotionally. Maybe it was too raw for me to process until this point in my life and songwriting is a great vessel for that, but not always the route I naturally choose to use songwriting for. Overall, The Clearing for me has reminded me and opened my eyes to the power of the song and what a song can do. I think after a few years of being lost in the wilderness of just being fascinated by all things production, I’m back into songwriting mode. And that was just an example of me experimenting with that.

Less was more

CG: I’ve understood and I would love for you to elaborate on it, both of you, that this album was a return to the song as an art form. And Ellie, I’m thinking about your storytelling all throughout. There’s so much I would love to talk about, just like girlhood and womanhood and all that you are laying bare here and some of your songs. But to take us back to composing and pulling these all together for The Clearing. How was it different for LP four after Blue Weekend?

ER: Yeah, it was quite different. I think we were quite inspired by after Blue Weekend, we made an EP called Blue Lullaby, where we just stripped back some of the songs from the album and played them in a kind of more raw, bare form. And I think it was kind of informative to us because we noticed how many things had how many parts, and stuff had got lost in the production. I love the way Blue Weekend sounds, I would never change it. It was interesting, you’d be like, “God, we put so much stuff in this, and some of it got lost.” Sometimes when you play acoustic shows and stuff like that, like people are like, “Oh, I never really heard that the song that way before.” So it was kind of like starting that with that in mind, but going forward writing songs. And that’s not for every single song on the record, but the bulk of the writing was like done that way before we got bored of that way. You know what I mean? Like, “What does this song sound like with nothing in it? And can I be proud of these lyrics if I was to sing them a capella?”

It’s always hard when you say things like that when you know that you didn’t stick by it 100%. It’s something that we were trying out when we were writing. But not like sticking everything in at all times and considering stuff way more than we ever had before, which isn’t to say it’s a better way or anything. It’s just a different way for us.

CG: Can you think of an example that maybe you added the least to? It’s closest to maybe the demo or the first version that you penned.

ER: Yeah. I feel like if “Bloom Baby Bloom” had been on Blue Weekend, it would have had maybe like 1,000 million tracks on it. It was really hard not to add like 10 harmonies and a thousand synths. And then “Safe in the World” was a really early one that we made that kind of informed our the style really in a way because we bounced the demo wrong and it came out just voice, drums and bass. I feel like we would have put a hundred tracks on that, like loads of different harmonies, loads of piano, bass, synths, you know, like lots of guitar. But because we bounced it wrong and we’d heard that it kind of sounded good with just these three elements, we were like, “OK, let’s not try not to put too much in there because it works just like this as well.” And that kind of informed us a little bit.

California’s good vibrations

CG: Was [The Clearing] recorded all in the same place or did you have multiple locations once you were actually getting the tracks down?

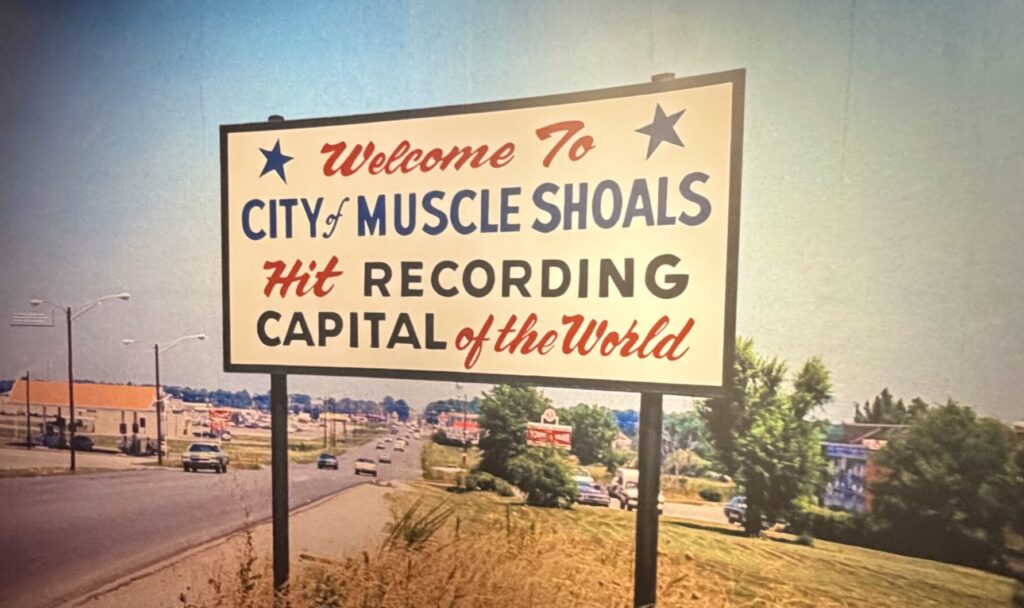

JA: It was all in the same place, yeah. We wrote some things in North London in Seven Sisters in a writing room. And what Ellie was referring to, that happened there when we bounced it wrong, wrong but right. And then we actually made the whole album start to finish with Greg Kurstin in his personal studio that’s in Hollywood, just off Hollywood in Los Angeles.

CG: What does coming to America do for you? Like is there any sense of place when you actually are recording outside of where you wrote the songs or not really? It’s kind of like “wherever you go there you are” as a band, I’m sure, but I’m always curious…

ER: I think going anywhere that isn’t home can be quite helpful in a way because you really got a sense of like, “I’m here to do something.” Especially when you go so far away from home, like somewhere like Los Angeles for us, it feels momentous and therefore everything you do you feels really important because you’re like, “I’ve come all this way.” I think going to America for all of us was like a dream when we started off and so you’re very aware that you’re very lucky to be there and you want to do a good job. Like sometimes you can be distracted if you’re at home.

Joel and I always say that going to Los Angeles, whether you like it or not, it’s steeped in music history, and there are a lot of creative people there, and there are a lot of people open to collaborating and there’s an air of creative excitement there. I don’t know if that’s because we’re from England and it’s very different. Like even when we went to a couple of parties and stuff, like people were whipping out their guitars and playing some songs. And we do that in England, but we’re a bit more shy about it or something, so it’s so exciting for a reserved, polite English person to see someone be so bold as to start jamming a party. It’s quite exciting, isn’t it?

JA: Yeah. Like when you say, for better for worse, I feel like in LA people aren’t embarrassed to say they’re in a band. And even now, when I see someone in my town and they ask what I do, I’m like, “I’m in a band.” I don’t know why that doesn’t [or] can’t have the same romance of bravado. So that means that you when you do go there you can get swept up and it’s like, “Yeah, this is what we’re here to do. This is important,” you know?

Lightness, not aggression

CG: It’s interesting when you said the creative energy of the place. It sounds like you mean present tense when you’re there, but also past tense. I hear influences on this record — I’m an American, obviously, but my favorite music was made decades ago in your country, really. And then I hear all sorts of sunshiny California tones on this, too. Can you speak a little bit to the inspirations going back? I know that lent to more minimal production when you thought about being in recording studios before you had all the tools. But can you talk about some of the bands and artists that you sourced when you put this together?

ER: We were kind of eager to make music that didn’t make us feel depressed. It felt like a challenge to write music that wasn’t dark. When we were growing up, I felt like I personally [would] gravitate towards kind of dark music and I really just did not want to be in that space. And I think there was a time I would always associate rock music with maybe a certain kind of darkness or aggressiveness. But back in the day, and — like you say — maybe from California, I still call like The Beach Boys a rock band or The Beatles are a rock band, you know what I mean? And but it’s not always so like doomy or grungy or whatever. There seem like a lot of like pop sensibilities, but it’s still rock ‘n roll and it’s still played on guitars and piano and organic instruments. So it was [for us] kind of just exploring what is a rock band, what can it mean? I don’t know about you, Joel, but I kind of grew up around indie music and was also into grungy music and then I kind of forgot that rock music didn’t have to be so dark and aggressive.

JA: No, definitely. We have very similar upbringings in terms of music and even like geographically, like the most informative years, your teenage years and early twenties and stuff, like when you go see bands, I felt like if you wanted to turn in a song that was like had shades of like happiness and stuff, it wouldn’t be taken as seriously. It would either go too twee or…you know. But this is a real skill. Like Ellie said, if you’re thinking about The Beatles and The Beach Boys and stuff, it can be melancholic but there isn’t this darkness and I think that’s what I found so exciting, as well. Blue Weekend was quite hard.

You were saying you started your radio station in COVID. Well, we were like four weeks into making Blue Weekend and then everything shut down. So we were there for quite a long time and it was incredibly inwards and introspective and I personally, after touring that, wanted a breath of air from that. And no disrespect to those songs ’cause I love them. But I was looking for something else and this seemed like the most exciting, you know, the most exciting path.

CG: Evidence of this lightness that you brought to this record was “Bread Butter Tea Sugar.” I’ve described it on the radio as jaunty. And it’s a great pleasure to play something that feels so good in a time that can feel so dark. So thank you for all the realness on this record and the moments of lightness that you brought in with the pop music.