In The Judds’ first country No. 1, 1984’s “Mama He’s Crazy,” the duo sang about the disorienting power of infatuation with a new beau, but they were really telling us about another relationship entirely: a daughter turning to her mother for some stabilizing wisdom while still heeding the intensity of her own emotions. In the music video, Wynonna Judd pines and puzzles aloud on the front porch, while Naomi Judd eavesdrops from inside, supplying supportive harmonies from that pensive remove. Flashback scenes indicate why Naomi’s insides are tied up in knots: Wistful about her own soured love affair, she worries for her daughter’s vulnerable heart. The clip ends with Wynonna stepping off the porch, determined to take her own chance, but not before looking back to her mother, for reassurance, or maybe something more like understanding.

A mother’s moral compass was hardly a novel song theme at the time. In the country, southern gospel and bluegrass canons, no earthly figure had been idealized above mom, depicted in saintly, sentimental ways that seldom actually touched down to earth. She “looked just like an angel” when she read scriptures to her children (“My Mother’s Bible“), comforted all within hearing with the sound of her nightly spiritual supplication (“Mother Prays Loud In Her Sleep“) and could even persuade a courtroom judge to let her rehabilitate a criminal son with her love (“I Heard My Mother Weeping“). The mere memory of her looking down from heaven could tug the heart toward home (“Dear Old Mother“) and set her gambling son back on the straight and narrow (“Mother, Queen Of My Heart“). Naomi’s emergence as one of the most famous mothers in country music was a revelation. What she embodied, on her own and next to Wynonna, was a complexity at once thoroughly down-home and thoroughly modern.

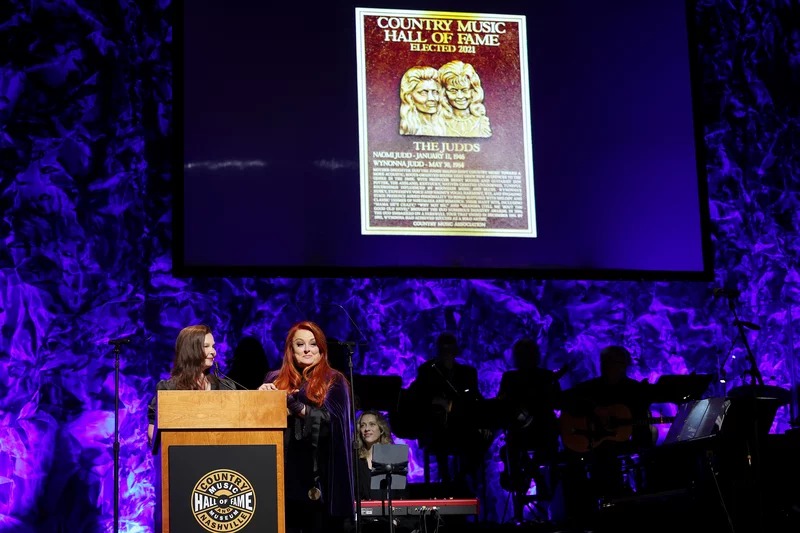

The Judds was one of the most riveting acts in country’s commercial history, whose five studio albums and two dozen charting singles endure in their quality and impact. Theirs was a vital but brief eight-year run, halted in 1991 by Naomi’s hepatitis C. From there, Wynonna carried on as a solo superstar, and they reunited periodically for short tours and special appearances. This year, the Judds were to come together again for the most special of occasions: getting their roses. Their induction into the Country Music Hall of Fame, their industry’s ultimate institutional honor, was imminent, and they’d embarked on what was billed as a final round of award show appearances, concert dates and promotional interviews. Instead, when The Judds’ bronze plaque was unveiled during the Sunday evening ceremony, Naomi’s youngest daughter Ashley Judd, the actor in the family, joined her sister Wynonna at the podium to give an acceptance speech that was proud, grieving and rueful. “I’m sorry that she couldn’t hang on until today,” Ashley said of her mom, who’d died the previous afternoon. The news had reached the world through a joint statement from both daughters: “We lost our beautiful mother to the disease of mental illness.” (The Judds’ most faithful and knowledgeable chronicler, Hunter Kelly, wrote about the loss from an intimate vantage point.)

A number of The Judds’ neotraditionalist peers — fellow figureheads of those ’80s and early ’90s waves of popular country credited with replacing artifice with a return to naturalistic modesty and simplicity — went into the hall ahead of them. One, Ricky Skaggs, was entrusted with formally welcoming them into membership during proceedings that were, at times, filled with an acute and expectant quiet. At the microphone on Sunday evening, he praised their realness, rootsiness and rural Kentucky bona fides at length — qualities they not only conveyed, but also complicated in rich ways throughout a partnership that somehow seemed simultaneously larger than life and true to life.

The Judds have one of the great, and greatly mythologized, country back stories, one that seems to encompass the social change of nearly the entire 20th century. Naomi was a single working mom, who did her best for her kids in times of backwoods and big-city deprivation alike, and a showbiz mom, who never lost sight of grander ambitions. She put herself through nursing school, and put a guitar in Wynonna’s hands; moved her family from a Kentucky mountaintop to California, where she and Wynonna traded the names they were born with (Diana and Christina) for the ones by which we’d come to know them, and ultimately a town outside of Nashville; she pushed their duo to anyone she met who had industry connections. When Naomi cared for the daughter of producer Brent Maher during a hospital nursing shift, she got a demo into his hands. By Wynonna’s late teens, the time when she and Naomi might’ve otherwise become less reliant on each other, they were — as retellings of their history customarily emphasize — professionally bound together. Naomi had willed the Judds’ career into being.

Much has been made about Naomi and Wynonna’s blood harmony, how kinship bestowed on them the gift of blending their voices as one. But there was more to it than what they were born with. They found their own dynamic, and out of it they forged a singular sound: a full-bodied, bluesy vocal attack over hot, rhythmically nimble, acoustic guitar-driven arrangements. That combination made them distinct from predecessors and formative for those who’d come after, mainstream stars like The Chicks, Sugarland and Ashley McBryde and bluegrass belters like The Steeldrivers and Mountain Heart. Where Naomi placed her harmonies in relation to Wynonna’s lusty lead mattered too: Mother seldom climbed above daughter to reach the kind of keening, cutting high notes that so many other harmony groups used to heighten feeling, but preferred to nestle beneath, a subtly bolstering and deepening presence.

In concert, the Judds were a study in contrasts, distinct in personality and generation. Their stage wear may have somewhat matched in the early days, but they moved on to expressing individuality in the realm of high country camp. Wynonna styled herself as a student of Elvis and Bonnie Raitt; she wore the pants and leather, copped her own version of rock’s New Romantic style, played guitar and strode on stage like she wasn’t to be messed with. “Excuse my language, but she’s a badass,” Naomi declared on a live album, meaning it very much as a compliment.

Naomi had her own ways of commanding the spotlight with flourish. She was the wryly mischievous, exaltedly ladylike one, peacocking around, her full-skirted dresses and gowns whimsically exaggerating the styles of Southern belles and old Hollywood. When they broadcast their 1991 farewell concert, Wynonna may have stepped on stage first, but Naomi’s was the more dramatic entrance; she paraded around the entire perimeter, twirling and waving on her way up front, a magnet for attention.

On stage in particular, Naomi was a defining presence, an impresario, comedienne and host who welcomed their crowds with her grand gestures. She had a way of inviting audiences in, as though sharing neighborly confidences and engrossing gossip, and knew just when and how to tug on the heartstrings. She amused and titillated, flitting around making folksy wisecracks, gleefully skipping up to the edge of what might be considered unladylike, as if to show that she was as earthy as ever, and offered up knowing self-deprecation. Wearing a shiny, red vinyl number, the first of several costumes, at that big farewell show, she put the spectacle in perspective: “Did you guys honestly think that somebody that would wear an outfit like this would just, like, disappear to a farm without throwing some kind of a blowout bash?” Before the night was over, she’d played up their humble roots and singularity alike, referring to Wynonna and herself as “a couple little redheaded girls from a small town in Kentucky” and “these two red-headed, boogie-woogie babes from Mars.”

Even when Naomi stood behind Wynonna, leaning over her daughter’s shoulder and looking into her face intently as she sang, it didn’t register strictly as an act of support, though it certainly was that — it also revealed guiding influence.

Sometimes mother and daughter made a joke of it. Perched side by side during an acoustic segment of that farewell performance, Naomi enthused, “The reason I love being on stage is that when I feel these lights, I just imagine it’s rays from heaven.” Wynonna didn’t even wait a beat before interjecting, “And you’re the queen of everything.” To which her mother replied, “So I guess that makes you the jewel in my crown, my dear.”

Together, the Judds transformed what country celebrity looked like, making their awards show speeches, Oprah interviews and, eventually, even reality TV series feel like personal disclosure, as though they considered tensions in their relationship something to be open about. They kept their family dynamic front and center; so many other performers had sung of their mamas in the abstract, but Wynonna often turned to hers for backup, lobbing, “Right, mama?” over her shoulder, or played the ham, dramatizing her exasperation. “They sang in harmony even when they didn’t live in harmony,” Kyle Young, CEO of the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, summarized on Sunday, eliciting an “Amen!” from Wynonna in the front row, despite the rawness of her loss.

The gendered lens applied to these interactions risked trivializing them. A generation or two earlier, country performers’ conflicts were confined to insider gossip. The tabloid era brought new scrutiny to famous lives, and presented country’s stars with new decisions about how much of their messiness to reveal. In the years to come, many would take in the lessons of media training and opt to manage their images and promote flattering portraits of domesticity. If the Judds had been a father-and-son unit, their interactions might’ve been spun as male bonding, a rite of passage to be respected, but Naomi and Wynonna often navigated extremes, any discord in their relationship either politely overlooked or, more likely, made the subject of dishy fascination. But whenever it was up to them, the Judds didn’t leave the telling of their story to others; they could do it more vividly themselves. Their acknowledgement that women of the ’80s and beyond didn’t necessarily share their mother’s conceptions of femininity or their aspirations should not be overlooked; it was no small thing in country music, where honoring elders was a core value.

When they did select songs that looked back, The Judds were carrying on a robust country tradition. In a nostalgic 1986 No. 1, they fretted, “Grandpa, everything is changing fast / We call it progress, but I just don’t know.” A few years later, they drew comfort from thumbing through old family photos in “Guardian Angels” and drank deeply of sentimentality in the handsome lost love ballad “River Of Time.” Those and other entries in their catalog were on some level acknowledgements that resourceful survival, seeking a different life and engaging in self-reinvention can generate a longing for sturdiness, a need to understand how the past could seem so simple in comparison. For the Judds, there was also an impulse to summon optimism and look ahead, as they did in one of their anthemic final hits, “Love Can Build a Bridge,” one of Naomi’s own compositions.

As much as Wynonna lent her voice to songs about soaking up old wisdom, she seemed plenty restless, voracious for her own experiences and immediate, potent expression. The Judds stocked their repertoire with tunes of frisky forwardness, like “Why Not Me” and “Born To Be Blue,” and reanimations of early rock and roll, R&B and country-blues — music of Naomi’s youth — that the two of them dared work up in ways that tapped into the live wire, liberatory energy of those styles and didn’t feel like retro exercises.

Naomi was no longer able to muster that boogieing energy by the dawn of the ’90s, after hepatitis C had wracked her body. She spoke openly about her disease, and why it necessitated her retirement, and made it known that she contracted it from working as a nurse to provide for her family. She continued to share about her physical and mental health over time, in later years, speaking and writing about dealing with paralyzing depression and anxiety. She’d strived for the country career that she and Wynonna shared, one that ultimately also made way for the fuller expression of her daughter’s artistic agency, and took every chance to serve as the narrator of her own story, to link self-sacrifice and self-actualization, to hold personal and parental aspirations side by side in ways that couldn’t be collapsed into the reverential iconography of country mother songs. “When we came here,” Naomi reflected, clutching what was presumed to be the Judds’ final Academy of Country Music trophy in 1991, “I was 37-years-old, and I didn’t think I had very much to show for my life at that time, and I pinned everything on – all my hopes, all my dreams, my name, my reputation and everything on this.”

9(mda2nzqwotg1mdeyotc4nzi2mzjmnmzlza001))