“Loving someone else’s art can give you a ride at least halfway to where you are trying to go. Even if you don’t know where that is yet.”

Celebrated singer, songwriter and, now, published book author Neko Case wrote this about her experience falling for the music of Ron Sexsmith when she was an up-and-coming musician and art student in Vancouver, B.C. But we don’t get to her mellifluous prose about music, not really, until about the last third of Case’s new memoir, The Harder I Fight, The More I Love You, released January 28. (I got to speak to this artist virtually just two days later, and a day before her would-be book tour stop in Nashville, which was unfortunately cancelled due to illness.)

Of course music animates and punctuates Case’s life, since before she banged the drums in punk bands as an emancipated teen and eventually embraced her own high lonesome country voice in young adulthood. But the story we follow is much more detailed and vivid — and, in fact, takes up the majority of this book — in her recollection of her childhood years in the Pacific Northwest and spurts elsewhere, ping-ponged between divorced and differently damaged parents, marked with indisputably too much solitude and capital-T trauma. So why and how did she choose to write so much, and so descriptively, about the hard stuff she experienced in her youth? Surely there were oodles of jumping-off points in the writing and editing phases of this work.

“I think because some of the situations were really bizarre and I didn’t have trouble accessing those memories or sensations. I wasn’t looking to hide anything about myself, really. The stuff that was harder was stuff about remembering, like, touring,” she said. “A lot of the years that I was on tour, I had a lot of anxiety. And so I just don’t remember as well as I do other parts of my life because I was just running forward and looking ahead. I was not present.“

Perhaps it’s a combination of Case’s memory lapse, and her intentional restraint in keeping her music’s meaning personal to her fans. “I didn’t want to go heavily into backstories of songs because I didn’t want to ruin them for people, because people have their own attachments to songs. And if you know too much about a song, it can wreck it for you,” she said. Regardless, readers beware that this is not some rock ‘n roll diary, a spilling of so much tea, though there are a few choice tales about her experiences in Tennessee that will raise brows here.

It’s more so the story of a “feral” little girl connected to animals and nature, navigating her world largely solo, disappointed time and again by the majority of the adults entrusted with her care. And it’s the story of that girl growing into a confident and collaborative troubadour, directing both her deep pain and her wide wonder into creative pursuits, because she can’t NOT. She remains a little edgy and reasonably suspicious, self-described as “someone with werewolf tufts who sometimes turns inside out.” In our chat, she eloquently railed on her own internalized misogyny — “The patriarchy is one of the greatest living parasites there is” — and the king-making kings in a still male-dominated country music industry, who “want a very consistent bag of Cheetos.”

But just as she traded the rural ambling of her often lonely youth for long night walks in grimy cities, making sense and making meaning, Neko Case continues searching for home and covering a lot of ground in that search. It’s a gift to tag along by listening to her songs (hallelujah, she has a new album to release this year!) and by reading this memoir.

Hear our whole conversation, including Case reading a passage from the book about being inspired by Loretta and Dolly, here and via WNXP Podcasts. Highlights from my discussion with Case are below.

Suddenly becoming a morning person

Neko Case: I was a little nervous to start [on this memoir] because, you know, I’ve been working on a book for a long time, but I didn’t really have a schedule for it. And that is fiction. So when I was approached by Grand Central/Hachette, I was excited because I was like, “Alright, I’m going to get to work on this book of fiction!” And they were like, “No, we’d rather pay you to write a memoir.” And I was like, “Alright, I guess we’re writing a memoir.” So I kind of had to get in a mindset for that just because writing about myself is not my first choice. I did not think I would be doing that. And I had to, I guess, figure out a how to be a writer every day and how to not be super boring to myself.

So one kind of freaky thing that happened was, I’ve been a night owl my whole life. I would stay up till three in the morning and work on stuff and get up at like 10 or 11. But right before I started working on the book, my body just said, “You’re getting up at 5 a.m. every day.” And just one day it happened. And I’m still like that now. I love it…I wake up before the sun comes up. I get some coffee and I really love just going back to bed with my coffee and having dogs and cats on me and just working on it while the sun is coming up. It’s very, very nice. And I started with just a little bit at a time and I had a really, really great writer and editor named Carrie Frye helping me with it. And she made it really fun because she knows a lot about writing and has helped a lot of people write things. And she understood that writing about yourself can feel just like walking through wet concrete or something. And so she would give me prompts and different viewpoints to see things from. And then it felt more like a game or a puzzle. And I began to really enjoy it because of Carrie.

Divinity in all living things

NC: My relationships with animals started very early and, you know, there wasn’t anybody telling me how to be with the animals or how to perceive the animals or to tell me that the animals were less than people. And it turned out that the animals’ behavior and affection was way more consistent than that of the adults. And so they were kind of my rocks. I didn’t think of dogs and cats as less than humans or other than humans. I didn’t think we were the same species, but I didn’t think that we were better than each other. Or one was more important or that one’s language was more or less sophisticated than the other…We were together and they made me feel good. And they liked me and I liked them. And it was just a very simple and lovely thing.

And I spent so much time alone in the wilderness that, you know, it just imprinted. And again, there weren’t people supervising me that were telling me anything about how I should feel about those things or, you know, I wasn’t given the education that most people get, like the Western idea that anything that isn’t a bug or a human or an animal is not living, like even plants are thought of that way. I naturally formed more of my ideas [that] were closer to what some indigenous people of North America feel about everything being living and nothing being more important than the other. As in, we’re all part of nature and nature is part of us and we’re all important.

Celia Gregory: I actually dog-eared the passage where it felt like a very profound lesson at the time of like, I don’t have dominion over animals and I’m not here to exert authority. I think it was with Sasha, right? You were taking out frustration on the dog and then you immediately knew that is not how you wanted to interact with animals. And it seems like that lesson lasted, that we’re not here to be better than, as you just said.

NC: No, that was like a result of trauma and frustration. And I lashed out. And even though I know why, like I still feel horrible about it to this day.

CG: She forgives you, though. That’s the thing, you know?

NC: I think she does. I think that I wrote really hard things in this book, but I think that was the hardest thing to look in the face and write in this.

What’s real country

CG: I’m obviously here in the country music capital, Music City, U.S.A. But I don’t know that you would be lumped in with country artists. It’s like it was your starting point. That’s where you were categorized in my college radio station. I remember pulling out your CDs from the “alt-country” section. It’s so silly that that was a thing and now it’s more of an umbrella term Americana. How do you feel about it now, the designation of country music?

NC: Well, the gatekeepers of country music are very white and very misogynist, and they’re very interested in making sure that country music does not evolve in any way. They don’t want country music as an art form. They want country music as a product. They want a very consistent bag of Cheetos and they don’t want women. You know, they’ve they’ve even said it out loud! “If you play more than one woman an hour, you know, people turn the radio off.” They don’t turn the radio off. Nobody slams their truck into a tree if they hear a woman’s voice. They really treat their listeners like they are completely stupid.

And I see a lot of really incredible, talented young women try to get in that door. I love them so much for it and I want them to succeed. But at the same time, like, those people are just waiting for them to say no because they know they’re going to say no. There’s no undeniable talent that’s going to make them change their minds. They are clinging tightly to control. And I always say, let that die. It’s a strangled colon. Let it die. Make something beautiful over here. Because country music is a real and vibrant thing started by women and people of color. Let it grow the way it wanted to grow, over here. You don’t need to do it there. Let it die.

CG: Yes, at it’s core, it’s more punk rock. It’s storytelling. It can be vicious. It can be dark, like real country.

NC: It’s music of protest and fairy tales and incredible stories.

Combatting the concept of competition in music

NC: I grew up in the’ 70s and ’80s and you know, the patriarchal message that I internalized was very effective. The patriarchy is one of the greatest living parasites there is. It is so successful. I was absolutely misogynist and threatened by other women and I believed that really bad misogyny slash rock ‘n roll mythology gem of “there’s just not enough room for women in music.” So, you know, you have to feel competitive with them all. Like, “why does she get that and I don’t get that?” And that’s sports. That’s not music, That’s not art. There’s room for everyone in music and art, literally everyone. And you can’t get enough.

It’s like books. You can’t have enough of them. And luckily you don’t have to! You can make it whatever you want. And when I realized that, I just realized where a lot of pain was living. And I realized that, you know, my reactions to things weren’t based on anything real. They were based on something that I’d been letting live rent-free in my body since I was a little kid.

CG: Earlier in the book, you were talking about finding confidence in working on cars and being able to do, like, man shit, you know. Then to find your voice and know of your skill and your worth. Not just, “OK, I’m not as acerbic about other women,” but knowing when you wrote “Hold On, Hold On” that it was a good song — in owning that, not just in the moment, but but repeating the story and saying, “Now I know that’s a good song and I knew it then.” I think that’s quite the journey, right, from being a scared and, as you said, internalized misogyny little girl?

NC: Yeah, and you know the reason that I was able to feel good about that song was because I wrote it with my friends, The Sadies, who I just think of as, like, the highest bar of musicianship. But by several years before that or many years before that, I had realized what reaching out to other women and supporting them could do. And it was such a natural bonfire that started. I made some of the best friends I’ve ever made. Women helping and holding up women was the greatest feeling. And we all just became, you know, twice as powerful for each other. And it didn’t take away from any of us.

On writing music for a stage production of “Thelma and Louise”

CG: Speaking of girl power, I understand you’re working with Callie Khouri on the “Thelma and Louise” music. Is that a dream gig or what?

NC: It’s like I don’t even know how to talk about that, really. It’s such a dream gig that, I mean, I was the target audience for [1991 film, screenplay by Callie Khouri] “Thelma and Louise” and, when it came out, I saw it in the theaters several times. And the first time I saw it, I remember standing up and going, “Yes!” My friend with me did, too. We were both like, “Yes!” I can’t believe like it was so empowering to hear those things said.

I met T Bone Burnett a long time ago, and that’s how I met Callie, because Callie and T Bone are married to each other, and we have just become friends over the years. And when she wanted to figure out who would do the music, she decided that she would ask me. And I don’t know anything about musicals, but. I know a lot about women and I know a lot about, you know, not just being a woman, but being a human. And what it feels like to just be stuck on one side when that’s not who you are, you know?

It’s been almost nine years and we’ve just kind of been given clearance to talk about it. So it’s really exciting to finally get to talk about it. But hopefully it’s going to be on stage next year. I don’t know. That’s just a stab in the dark. But, you know, we’ve been. staging it and we’ve just added dancers and it’s wildly compelling. I am so in awe of everyone. It’s a masterclass in songwriting and storytelling, and it’s the most collaborative thing I’ve ever done.

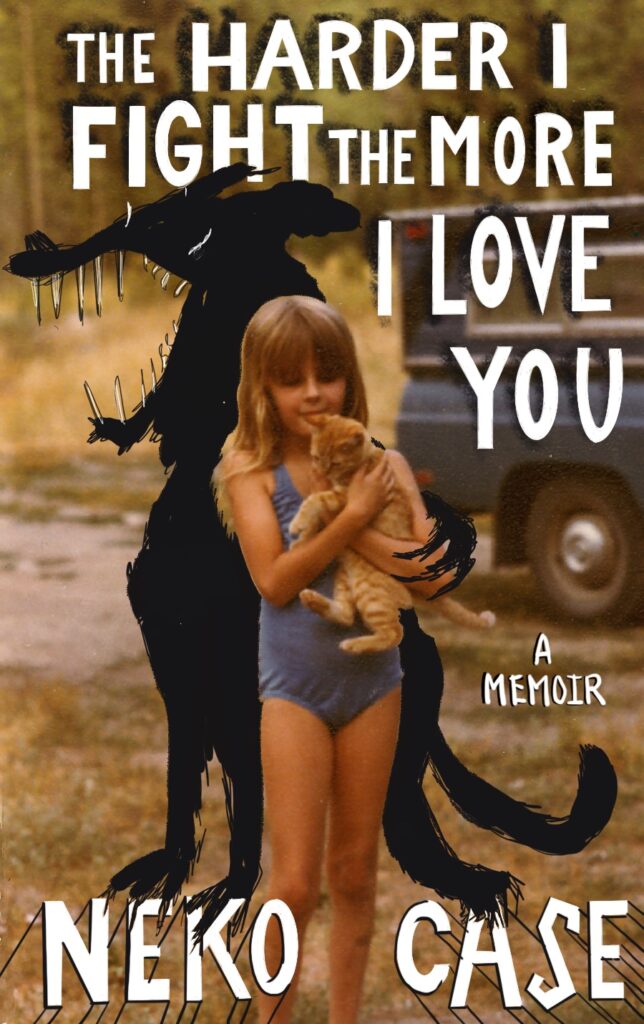

Book cover credit

NC: I went to art school in my 20s and I was excited to write the book. But I really wanted to make the cover. [Laughs.] And they let me. I don’t know why they did, but they did. So I got to do the cover for the book. And I think I was so much more excited about that than anything.

CG: Why? Why do you think?

NC: Because I love to to do things with art and design. And I never get to, I never get to use my art degree.

CG: Really? So even like with all early albums and stuff?

NC: Oh I could do it on my own albums, but like, yeah, you know, that’s because I have veto power. Nobody can stop me. But in this particular situation, they could have and they didn’t. And I’m so grateful to them for that.

Starving for home

CG: You’re on book tour now but have spent a lot of your adult life — nay, the whole adult life — touring and you’re a pretty mobile person. You’ve also lived in all corners. Maybe not Florida, but like all corners of our country, if I’m not mistaken.

NC: Yeah, I did live in Florida. My dad was in the Air Force when we lived in Cocoa Beach.

CG: That’s right! So I’m curious about not just, you know, compare and contrast about the places you’ve seen. You do talk about that, about touring and finding the natural splendor between dirty rest stops and stuff like that. But what is home to you now? What is the essential ingredient if it’s not a geographic place that makes home home for Neko Case?

NC: Well, since my house burned down in 2017, I haven’t found it since. Like, I’ve actually been starving for home. And it’s really a common thing with people who’ve had a lot of trauma as children that they are very focused on home and they need that rejuvenated space. And I’ve been taken advantage of by many contractors and my house still isn’t finished. And now taxes in Vermont are too high. So I don’t know if I can stay. So I’m still on the lam somehow and would love to be home, but I don’t quite know where that is yet.

CG: Gosh, I didn’t think about the timeliness of your connection to all these folks that have just lost a lot in California. To be the victim of fire…

NC: Yeah, it’s it’s crazy. But the thing people in California have going for them, even though it is also a tragedy, is that they do have each other to lean on and community to help. It was pretty lonely the way it happened to me. But it was also at the same time that Houston had just had massive hurricanes and floods and Puerto Rico was under water. And, you know, what was I going to say? Poor me? I mean, nobody had died. I didn’t lose any loved ones, I lost stuff, right? But, you know, I didn’t see it at the time. I didn’t think it would take this long. So I did lose home, and I still haven’t found it. When I see the the devastation in California, I just have such an ache for them because I don’t want it to take so long for them.

CG: To find home again?

NC: Yeah.