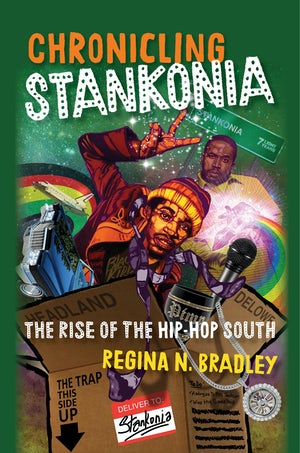

If you want to develop a deeper appreciation for the cultural significance of southern hip-hop, the scholarly work of Regina Bradley is good place to start. She’s on the faculty of Kennesaw State University, she’s the co-creator of the Bottom of the Map podcast on Atlanta’s WABE and she’s written an important new book titled Chronicling Stankonia: The Rise of the Hip-Hop South.

Jewly Hight: I didn’t plan it this way on purpose, but I think it is pretty cool that we happen to be speaking on the anniversary of Speakerboxx/The Love Below winning album of the year on the Grammys.

Regina Bradley: It’s a good sign from the universe.

JH: Before we before we dive into your new book, I wanted to ask you about your work at Kennesaw State. How do incorporate your scholarship on southern hip-hop into courses that you teach in the English department?

RB: I usually teach a survey of African-American literature class, and the first unit is focused on more contemporary writings. One of the assignments they have is do a protest music playlist. So I get to use my interest and expertise in hip-hop to have students think about hip-hop as a means of protest and resistance, and also help them understand ideas about protest and resistance aren’t always going to be what they usually see when they think about something like the Civil Rights movement. I also get to teach upper level classes. This semester I’m teaching my Outkast class, which is my signature class on campus. In the fall, I think I want to teach a class on women in southern rap. Being able to connect upper level classes to my research interests keeps me on top of my game and helps me to keep my teaching fresh.

JH: I bet your Outkast class is packed to the max every time you teach it.

RB: Yes, less than a week after it’s open for registration. I’m very proud of that.

JH: At this point, I think people are aware that southern hip-hop is a commercial and cultural force, but they probably don’t give as much thought to the serious scholarly and critical work on it. As a leader in that field, where do you feel it is in its development at this point and why is it important?

RB: One of the things that I hope to achieve with the book is to show that Outkast didn’t just happen in a vacuum. That’s the first thing. This idea of southern rap isn’t as oxymoronic as folks would like to think. Rap does happen in the South. We just pull from different experiences that come from living below the Mason-Dixon line, so to speak. People like to think about the South in a very linear way, meaning, “This happened, this happened, this happened.” But in the South, especially in southern Black communities, it’s cyclical. There’s always a revision of how we how we think about things, how we engage things. One of the things that I want to put through is that if we think about southernness as cyclical instead of linear, then that opens up the possibilities of thinking about the contributions that southernness has made to the larger overall American pop culture landscape.

Unfortunately, in the Academy, things are extremely slow; folks pick up on things really slow. Even though hip-hop studies has been a thing for almost 30 years now, that’s still considered to be extremely new. And a lot of those studies had nothing to do with the South. They didn’t really think about regionalism in the way that Chronicling Stankonia does. So I’m hoping that it opens up the conversation further about the significance of not only hip-hop from a regional perspective, but also thinking about the ways that hip-hop updates conversations about Black identities and expressions in the in the post-Civil Rights era.

JH: At the start of the book, you establish how contemporary, Black, Southern identities—especially for people who are generations removed from the Civil Rights movement of the ’60s—have been constricted by perceptions from outside the South, and also impacted by older generations’ expectations and tellings of Southern history that prop up white supremacy. How do you see southern hip-hop, and Outkast’s music in particular, as a site for fleshing out more complex identities?

RB: When I teach the Outkast class, the first thing I ask my students is, “When were you first Outkasted?” Most folks start with Speakerboxx/The Love Below. And I’m like, “It’s so much deeper than that.”

The comfort zone for a lot of conversations about hip-hop still remains the northeast or the West Coast. And that’s all well and good, but for those of us who don’t engage with the northeast or the West Coast on a daily basis, we need to find our own context, our own framework for thinking about this music that’s coming out of our region. So hopefully the way that I introduce Outkast as a framework for thinking about how conversations about hip-hop is updated can be extended to other groups in the South and other and what they’ve contributed to the larger conversation.

JH: You call Outkast’s Big Boi and Andre “founding theoreticians of the hip-hop South.” What are you getting at there?

RB: I’m not saying that they were the first southern rap group. That’s not what I’m saying. What I am saying is that they paid the dues be recognized as the first southern rap group. Their sound was different. They weren’t trying to pull from New York. They weren’t trying to pull from anywhere else but Atlanta, and they have [the Atlanta production team] Organized Noize to thank for that. So when I say that they’re the founding theoreticians, it really means that they open up the possibilities of what southernness can sound like in hip-hop. There is no universal formula for southernness and southern expression. Southernness isn’t monolithic. Blackness isn’t monolithic. So why would the music and the culture that’s coming out of those places be monolithic? There is no cookie cutter.

Outkast is a great way to work through that. If you think about their first album, Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik, it comes out in 1994. It sounds completely different than what you get with Speakerboxx/The Love Below almost a decade later. So being able to continuously evolve their sound to reflect not only how they’re thinking about themselves in the world around them, but also how they’re thinking about the potential that hip-hop has to be a mode of expression is really useful in thinking about this idea of a founding theoretician. Because all the theory is, is an educated guess, and you have to apply it.

You have Outkast introducing funk and gospel as places to pull from for hip-hop. At the time, hip-hop was supposed to sound and sample in a particular way, coming out of New York. I tell students to listen to Nas’ Illmatic, which comes out about a month before Southernplayalistic and compare the sounds. What do you hear? [On Illmatic] you hear the subway system. You hear all of these sights and sounds of New York that make it in New York. And you hear the exact same thing on Southernplayalistic. The “Welcome to Atlanta” skit, for example, is the captain of probably a Delta flight giving you the sights and tours of Atlanta as this burgeoning city. It’s not just this small urban hub regionally. It is now this internationally known city, and the airport is the best way to sonically reify that.

When you get to ATLiens, they start to incorporate more of those Afrofuturistic sounds. You think you’re watching something from Star Trek, Lost in Space. They don’t return from the [1995] Source Awards [where they were named Best New Rap Group and booed by the New York crowd] saying, “OK, we’re rejected.” [Instead] they said, “We’re not accepted in New York. We’re not accepted anywhere else. So we just gonna go to space.” So you get ATliens. There’s not a loss of Atlanta. Atlanta just moves.

And then when you get to something like Aquemini or even Stankonia, Stankonia is a completely different world that doesn’t really fit anywhere. So where do we put that? Seven light years below sea level in the middle of Earth. And what is the middle of the earth? Well, hip-hop makes the world go around. Being able to show the continuous evolution of not only just southernness but also the capabilities of what southern sound can be is why I give Outkast that title.

JH: Anyone whose Outkast entry point was their breakthrough double album Speakerboxx/The Love Below probably associates them with massive pop visibility. What sort of outsider quality were they getting at early on by choosing the name Outkast?

RB: What happens at that Source Awards in 1995 is the culmination of so many different things. It’s the height of the East Coast/West Coast rivalry, and you have this group coming out of Atlanta that nobody is checking for like that, because it’s the South. And then Outkast wins, and they’re met with this onslaught of booing. It’s just disrespectful. To be able to hold some kind of composure, a lot of folks will give Big Boi credit for that. He was like, “We know we’re in your city.” Then Andre gives this rallying cry: “The South got something to say.” And what we have to say is different than what’s already been said, how it’s been said.

Up until that point, hip-hop was so essentially northeastern that even when it tried to take root in the South is still was a reflection of New York, not necessarily of the experiences in the communities that it was taking root in. So once you have this rallying cry, it is the introduction of the hip-hop South, because it opens the door for all of the southern artists and rap labels that are going to basically bust through the door.

JH: You pinpoint the work of bringing black Southern identity into the present and also reckoning with the past as being a throughline in Outkast’s recording career

RB: Southernness isn’t stagnant. There’s this expectation the South is only this one way. Folks like to glorify this idea of the Old South. And I’m like, “Who’s it glorifying?” Who it’s glorified for is definitely not Black folks, because if we’re glorifying the Old South, we’re glorifying everything that comes along with it, including slavery. So we need something a little bit more updated. That can’t be the only reference point. The Civil Rights movement can’t be the only reference point for understanding how southern Blackness is has evolved. And hip-hop was that intervention point, and being able to connect those things in the book to not only just Outkast, but also other young creatives who are doing that work, from Kiese Laymon to Jasmyn Ward, just being able to show that it’s complicated; we’re complicated; we have layers.

JH: When you talk about the Afrofuturism of ATLiens, you point out that it’s a vision of Black people remaining in the South and not not migrating to some northern city, but pushing into other kinds of imaginative space. How did they flesh that out, sonically and lyrically?

RB: I mean, “Elevators” really just is perfection. It’s important to note that that was one of Outkast’s first attempts at producing [themselves].

Basically, Afuturism is Black folks thinking about themselves and projecting themselves into a future where folks don’t want to see them there. Sonically, they did that by pulling from the funk esthetic. So you have the idea of the mothership, for example, and that’s borrowed from Parliament. Then being able to articulate that, using more touchstones of pop culture that immediately come to mind from the ’80s, which is when they’re coming up. The “Elevators” video, for example, pulls from Predator. Just being able to combine all of these things into this really beautiful, even haunting track that pulls from the traumatic experience of running to freedom, this idea of freedom from a slavery perspective, the idea of freedom from a more contemporary perspective, the idea of freedom as an act of emancipation and futurity for folks who are coming up behind you.

The opening to the whole ATLiens album is, “Greetings, earthlings. Take me to your leader.” That stuff is a continuation from the first album, but also this understanding that, “Hey, we have to literally reimagine and force ourselves into the future, because if we don’t do it, nobody else will.” So I think that that’s the idea of establishing a point of truth for Outkast is really important. Being Outkast, it doesn’t necessarily mean being accepted. Being free doesn’t necessarily mean being accepted. That’s one of the most powerful things that makes their music so significant, is that willingness and that courageousness to continue to experiment with how they see themselves because they’re speaking their truth and folks are picking up on that and using that to establish their own point of entry to getting to freedom as well.

JH: You touched on Stankonia briefly. What world-building work do you see them doing on that album?

RB: I think they pulled it off mall from all sides. Stankonia is when Earthtone III really starts to take over, which is the production team of Outkast and Mr. DJ David Sheats. So this idea of the apocalypse, and then to start Stankonia with, “Live from the center of the earth.” Something survived that apocalypse, and what was it? Well, it was southern rap. You can’t get much more South than the literal center of the earth, if we want to take it that far. I’ll die on this hill: I feel like Stankonia, in terms of the skits, is the best ever in hip-hop. They’re great. They’re humorous. They’re real.

The opportunity to create southernness as a world-building experiment is most amplified with Stankonia because it’s speculative in ways that something like Southernplayalistic wasn’t, because Atlanta is a real place, but Stankonia technically is not. So there’s not those historical, social, cultural boundaries in place to think about space. They could just, you know, improvise. And that’s exactly what they did. And it came out really great.

JH: At the end of the book, you look toward the future and cheer on the work of your fellow scholars and younger generations of critics coming up who are doing work on southern hip-hop.

RB: I feel like it’s a big table and everybody needs to eat. There’s such a lack of scholarship and critical analysis into why southern rap is such a complicated thing. I just really hope that the book opens the door, because I wouldn’t be able to study Southern rap without a lot of the pioneering southern journalists before me, Joycelyn Wilson, Maurice Garland, Charlie Braxton. But also seeing that there are younger journalists who are coming up who are representing for the South, and being able to put them in conversation with what’s already been put out. I’m not only continuing the tradition of criticism, but also broadening the conversation. We’re in desperate need of that, to broaden the conversation about what southern rap is, where it’s going, where it’s headed, but also where it’s been. Hopefully Chronicling Stankonia is an opportunity for folks to get a little bit of insight into that, and to do their own research as well.