Fans of the music made by celebrated songwriter and Southern rocker Jason Isbell have come to expect that he’ll tell it like it is, through lyrics illustrative of his complicated past but also of his present values, which are reflected in a robust social media presence, too.

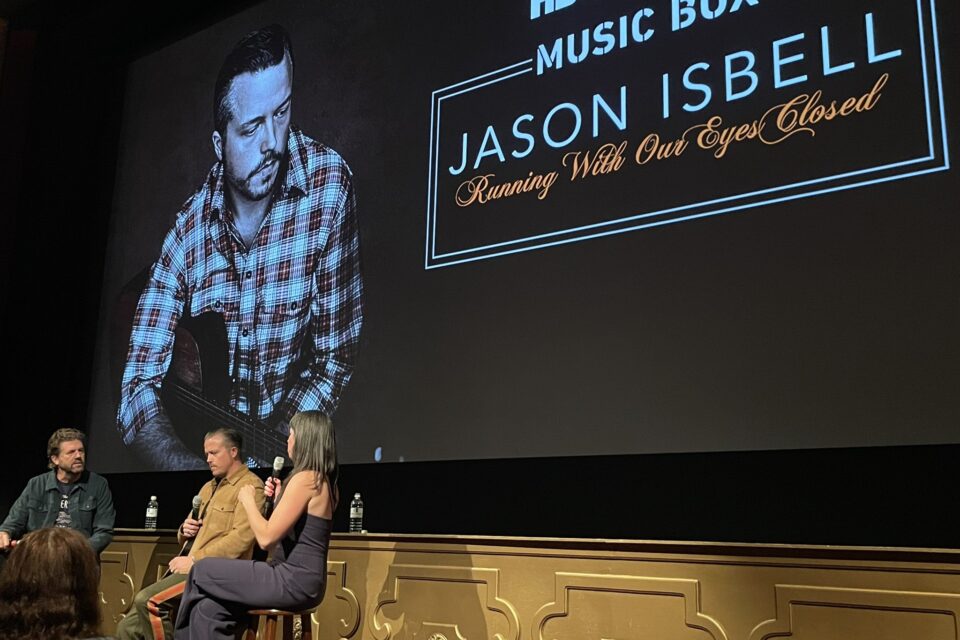

More vulnerable than tweeting, though? Having cameras rolling steadily on not only your creative process but also your personal fissures and foibles, punctuated by a global upheaval. The documentary “Running With Our Eyes Closed” — now streaming on HBO — chronicles all of the above in a “vérité” meets “biography” 90 minutes about Isbell’s craft and key relationships, especially his marriage to musical collaborator Amanda Shires.

I had the great fortune of meeting the filmmaker Sam Jones at a special late March film screening hosted at Nashville’s historic Belcourt Theater. Catching up over Zoom once Jones was back in L.A., we both reflected on the incredible openness of the documentary’s subjects, and how Jones’s ability to pivot the storytelling made “Running With Our Eyes Closed” so much more than a rock doc.

On the Record: A Q&A With Sam Jones

Celia Gregory: I’m talking with Sam Jones, who’s based in California, but was just here in Nashville for a great event over at the Belcourt Theater — a sold-out screening of his new documentary about Jason Isbell called “Running With Our Eyes Closed.” In case you weren’t in that room, I wanted to get Sam on the horn to talk about this project, which premieres on HBO April 7, and then will be available for streaming on HBO Max. It’s a real treat to have met you, Sam, and talk to you again today.

Sam Jones: Well, thank you for having me. And thank you for moderating our screening, because I didn’t know you before the screening. And now I feel like I know you and you did such a great job. And I’m a big public radio proponent and it was so nice to also get to know a little about your station. So I’m glad I met you.

CG: Well, you’re welcome up to WNXP anytime. If you want to co-host, you could add that to your long CV. I feel like it’s hard to even introduce you, but because this is a music station and relevant to this current project, I’ll point people to “Running With Our Eyes Closed” and ask first: how did you come to know Jason Isbell, and why did you think that this documentary, a long form piece into his life and his work, was worth tackling?

SJ: I had this show called Off Camera for a long time that was on Netflix and also on DirecTV. And I had Jason on the show because a friend of mine turned me on to his music and I liked it, and I wanted to know more about him. Once he was on the show, I sort of couldn’t get his story out of my head. I was so curious about how many of the things he wrote about, how true they really were. And he just seemed to me like one of these artists that really mined his own life for material. Those are artists that I often gravitate towards. And I got to be honest, I don’t think there are a plethora of great storytelling lyricists out there that I’ve found, my earliest experience being Bob Dylan when I was in high school. But when you stumble across somebody that can really write in a way that a great novelist or a great poet can write, it’s something to be treasured.

I wasn’t looking around for the next film to make. And those are usually the best kinds of ways to start a project when something just keeps kind of eating at you. And finally, you think to yourself, “Well, maybe I should just go try to tell his story.” And that’s what happened. Jason was really generous. I went out to the Ryman shows and went backstage, kind of pitched him on the idea, and he was immediately in and we were off to the races.

CG: I think you said the other day you started and finished your Tony Hawk documentary in the same time it took to complete this Jason Isbell piece. So can you address the timeline, from advent of that Ryman invitation to the beginning of filming to here we are, this thing is ready for public consumption?

SJ: Well, it started out pretty quick. I think I asked him in August or September, and then by the end of November we were in the studio with him and he was making Reunions, which was good timing, that he had a record that he was ready to record. And so everything was going along quite swimmingly until March 2020, the same day my kids school closed and the NBA basketball season ended. I think that was March 13. We were in Nashville and doing interviews with Jason and and all of a sudden the discussion turned to how can we get our crew back home and are they going to shut down flights and all that. So that was the beginning of this film taking much longer than we originally anticipated because Jason was figuring out, how am I going to release a record, how are we going to deal with the timeline and press? And from that point on to actually HBO, acquiring the film I think was almost two and a half years.

While I was waiting for all of that to happen, I went and made the Tony Hawk film because he lived down the road from me. I say down the road, he was in San Diego, I’m in Los Angeles, but we were able to make this documentary about skateboarding in people’s backyards, and it was a much quicker process.

CG: COVID, of course, is a pivot point, not just in everybody’s lives, but in this film. It’s about the making of the record and how they had to adjust with how they promoted it. And course you capture right here in Nashville at Brooklyn Bowl, them doing this sort of half-assed release show. It was just Amanda and Jason and how disappointing that was. So it is still about the creative process, but something else is afoot. Something else is happening in the personal lives of Jason and his wife, Amanda Shires, and that becomes the core of the story. Besides the musical journey that Jason’s taking us on and you going back into his history and his upbringing, it’s very comprehensive about Jason as a songwriter and where he’s come from, but there’s something very present tense about his family life. When you were working on this and bringing it to completion, how did you handle that content?

SJ: You know, we went into the studio to watch how Jason wrote and recorded music and how he presented it to the band and how the band interpreted it. Because Jason, you’ll see in the film, has sort of a unique way of working. He does not let his band hear the music before they are ready to record it. So it is a brand new experience for his band, and he hopes to capture lightning in a bottle through that process. And that’s a pretty high wire act. I always love when creative people do things that are a little riskier. That was the initial impetus that I thought would make a interesting visual thing to film too, because you got to see all these musicians trying to interpret and figure out what to do with the material when hearing it for the first time.

But it quickly became obvious to me that the relationship between Jason and Amanda, it affected all other things. Especially in storytelling, once I figured out the dynamics of Jason and Amanda’s relationship, I realized that that was sort of the fulcrum that we could take you back into the past and then back to the present. I think it’s no secret if you follow Jason and Amanda, they’ve not had the easiest marriage. And Jason has also had to deal with his sobriety and his recovery. But what I found was by really focusing on that relationship, it opened doorways into all the other chapters in Jason’s life.

Then when the pandemic hit and Jason and Amanda were sort of forced to be in a house together and they couldn’t go off on their separate tours and stay in their comfort zones, but they had to get to know each other in a different way that was much more intense and one-on-one. Those themes resonated with all of the other things that we had been capturing in the doc. So Amanda, in a way, sort of became the the thing that we hinged the structure of our story on. That made the structure of the film work because it’s hard to mix a verité doc with a biographical doc and find ways back and forth and and not have a situation where the audience is waiting through one story to get back to the other story.

CG: Well, it’s really elegant in its presentation, and yet it’s like a time capsule, right? Here we are three years later, and they even said on the side of the stage — and I don’t think they would care about me repeating this — “I wish we could do a follow up so they can see how happy we are now!” It’s kind of hard to go back to that place.

This experience filming included a forced adjustment in how the story turned out, but also how you technically had to do this thing. You had to turn the camera over quite literally to Jason and Amanda so they could film in their own home. A major shift in the project. But it provided this, like you said, doorway. Somebody in the audience [at The Belcourt] asked you about the similarities in this story and then what happened when you were shooting “I Am Trying to Break Your Heart,” the Wilco documentary. Do you mind reiterating your answer about that awareness that you had maybe later than others, that this was an opportunity for this film to be even better than it would have been before, even though you were forced to take a new direction?

SJ: I went into each film with one sort of agenda because you have to have an agenda. Even with hindsight and 20 years later, I understand that that John Lennon quote, you know, “Life is what happens when you’re making other plans.” And you have to have a plan. But I know enough now to know that that plan is probably going to get upended. And I think with the Wilco experience, it was a real challenge to figure out how to follow the story when it started veering off my plan.

But what I learned in both cases was that as a documentary filmmaker, if you stay open every day to the present events happening in front of you and not try to force what you’re doing into a direction, then you’re going to make a film that reflects what’s going on better. I don’t want to give too much away, but there’s a very emotional moment in the film with Amanda, and that was one of the interviews that took place remotely. I was in Los Angeles and and Jason had set up the camera, but then he left the house and went out to the barn. And so it was just Amanda in her bedroom and we did a long interview. And I think at a certain point she’s just surrounded by all her things, her bed and her nightstand and the pictures of her family and everything. And I don’t think there would have been that much of a reveal or an intimacy or an emotional comfortableness if I was in that room with her.

CG: Yeah, the moment you mentioned is one of many moments where you realize how vulnerable it was for them to open their lives up in such a way. And Jason basically said, “As long as Amanda was cool with it, I was cool with it. And we shared everything. We want this to be real.” Is that something, Sam, you’ve found is the exception or the rule to your subjects?

SJ: I do think it’s the exception in what we see most in life. It’s hard to get people to open up, and it’s hard for people to feel comfortable on camera. But for me, it’s sort of the rule in the people I choose to work with. The first time I ever spoke to Jason about this, I said, “I really only have one rule, which is that you have to trust me.” Watching Amanda be so brave and honest and sometimes even more sharing and vulnerable than Jason gave him not just the license to be that way, but sort of the challenge to be that way.

She’s a pretty fearless artist and he is as well. Jason says they have a rule about songs, which is that if if some lyrics in a song he’s writing makes him uncomfortable, that it has to go on the record. There was a moment when he answered a question for me, and it’s in the film where he says, “I have to accept not looking cool or not looking necessarily my best all the time in order to be a real artist.” And I put that in the film right in the beginning because I thought, OK, Jason’s going to be the first person to see this film. So I’m going to remind him that he’s not always going to look cool in this film, but it’s important to for him to be an artist.

I think a lot of people don’t trust that a human just being honest and real is interesting enough. Obviously with a lot of what we see in reality shows and more heightened emotional documentaries, you feel a little bit, as an audience member, like you’re being marketed to or you’re being lied to in service of ramping up the drama. And I just tried to trust that what was happening, even though it was subtle, was still going to come across and that Jason and Amanda were going to honor their commitment. And that did come to fruition.

CG: The “I Am Trying To Break Your Heart” Wilco documentary is how I first learned of your work. You have before that and since done a whole lot as a photographer, a filmmaker, and then your show that you mentioned [Off Camera]. Are you at a point right now where you can be a little choosy, it sounds like, with whose stories you find interesting? You said you weren’t searching for this. You became acquainted with Jason and thought there was more there. How are you in general approaching your creative and professional life when there are so many fascinating people making so many cool things? You stay busy, but what’s your thought process around the next projects you’re trying to tackle?

SJ: Yeah, that’s the big question always. I started out in a world where I needed to wait for the phone to ring. As a photographer, you did your best work, you put it out there. People saw it in a magazine or in your portfolio or whatever. Hopefully you get the call. And that has certainly changed in our business.

In general, I would say that a lot of creatives will tell you that the phone’s not ringing with an offer for the best work. Maybe if you’re making the next Marvel film or something like that. But for me, it’s difficult because I know the pitfalls that come with a project that is this complex in scope. When you take on a documentary, you know you’re in for two or three years of pushing this rock up the hill and there’s no one helping you. Most of the time you’re having to figure it out yourself and it’s difficult. And then if you if you choose wrong and either your subject is not who you thought they were or is not as cooperative or the terms change or the producers you’re working with…whatever it is, it can get really difficult.

Choosing to do a project, it comes with a lot of a lot of anxiety. I think that if it’s a narrative project, then it’s a lot about how do you put something together that has so many moving pieces. All I can do is kind of keep my mind open for things that seem interesting to me. And then you go after them — you put ten things out there and maybe one shows some promise and you start pushing that one down the road and seeing if it gathers any traction. And then you also have to keep your mind open for other things. I don’t have the answer to how to do it right. I just think that somehow I keep on finding the next thing that gets me excited enough to want to do the work, you know?

CG: Well, somebody close to you said, “Oh, he just goes after the things he likes to do,” like the cool stuff, your hobbies. You just want to interact with the people that do those things, so you get to spend time in those environments. Is that the shorthand?

SJ: That’s the dream. You know, I will say in the last couple of years, I’ve had two pretty disappointing experiences to where there there’s projects that I really wanted to do and for different reasons, they just didn’t work. And that’s just this business. I have many of those in my past and with all the best intentions, you know, these things still need a lot of luck and kismet to make them work.

I remember once around when I was starting Off Camera, my producing partner said, “What’s your goal?” And I said, “I don’t think I want to have any clients.” In other words, I don’t want anyone to have the ability to have to say yes or no before I get to do the thing I want to do. And that has sort of driven my philosophy.

I’ve probably in some ways missed out on some bigger opportunities because I wanted to do things independently. But when you do something independently and you bring it to fruition and it works out, it’s the most satisfying feeling for a creative person, you know, to have an idea and shape it and mold it and get a bunch of people around you that believe in it too, want to do it together. When you finally pull it off, it feels pretty great.

CG: Well, you definitely pulled it off with “Running With Our Eyes Closed.” I think people are really going to love this film. I do. I’ve now seen it twice — I only blubber cried the first time because I wasn’t in public. But it’s really beautiful.

As a postscript, I would love for you to remind folks what you told me on the side, just so casually, that not only have you been on the radio and sort of started your own radio show, you’ve also run a record label! You’ve done stuff in music before. Does that feel like ancient history to you now?

SJ: Not at all, no. As a matter of fact, I grew up loving radio so much — I grew up without a television in my room or a smartphone, obviously. So I had the radio and I could turn it on low enough that my parents couldn’t hear it and I could listen late into the night. And so I always have a romantic association with radio hosts that create sort of a magical view of the world.

And yes, in my past, I had a little house in the mountains and in this tiny community there was a guy that ran the gas station and the video store. He put an antenna up and he made probably the smallest radio station in the history of the world. I asked him if I could have a little show, and he said yes. And so I prerecord my little show in my garage and would have my friends on who are musicians and I’d interview them. And I loved it. I’ve always loved the variety show. I’ve always loved following somebody that could turn me onto interesting artists, whether they’re musicians or filmmakers or authors or whatever… just getting lost in someone’s passion.

I’ve also always played in bands and I had the opportunity to join an independent record label out of Seattle called Loveless Records. That was started by my friend Pete Nordstrom and John Richards, who’s a DJ at KEXP in Seattle. The three of us had this record label and for me, getting to help bands make records and get excited about music and then try to get them out on the road and learn that side of the business was so fun. We lost money the whole time. But I loved the experience. I got to be a producer, I got to be a promoter, I got to be a journalist, all the things that you have to do at a tiny level. And then I learned about licensing and contracts. I use all that stuff every day now in whatever I’m pursuing. And those are some of my favorite memories before having kids.

CG: I love that. Well, and I want to welcome you on for my little show anytime you want to co-host. We could pre-record, you could come up live. It is fun. And I love that radio is part of your long pedigree. Thank you for all the creative work that you are putting into this world and especially, you know, illuminating real people’s stories so that we feel closer to these music makers because we feel like we know them. As you said about Jason initially and again, Jason and Amanda Shires, their life is on display in “Running With Our Eyes Closed” — as well as the art of Reunions, the record made during filming and that came out in 2020. Here we are at the beginning of 2023, before Jason’s new one comes out called Weathervanes. So it’s a full circle moment. Sam, I’m so grateful that you wanted to share time with me.

SJ: Well, thank you. And be careful what you ask for, because I’m sure you’re not going to be able to get rid of me. You know, my dream is to be a radio host, a legitimate one, not one at a gas station radio station.

CG: We all have our humble roots, you know?

SJ: I thank you very much, it’s been a joy talking to you.