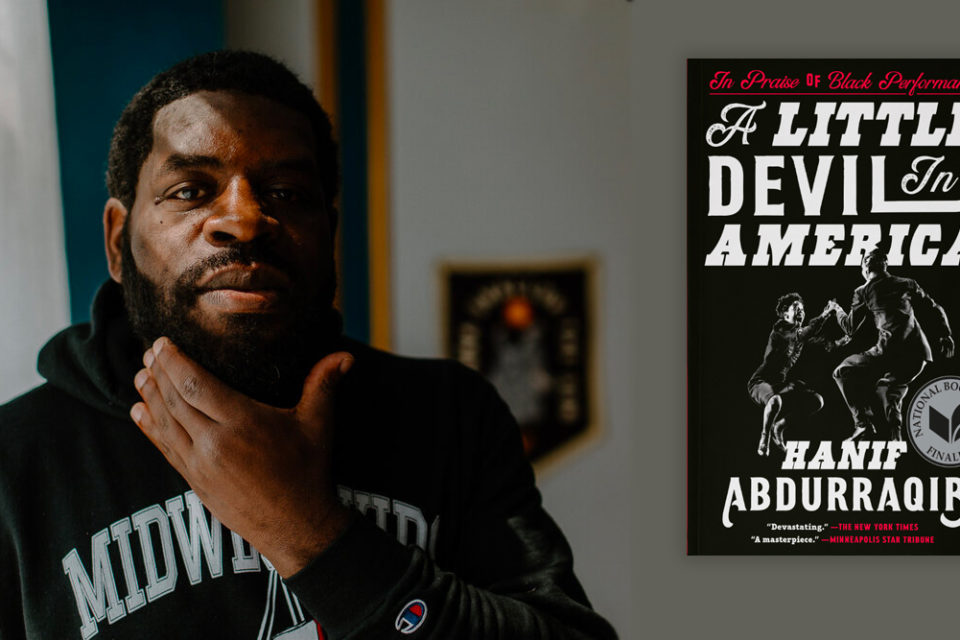

It’s been a good, long while since we’ve brought you a new entry in our Culture Club series, those conversation with folks whose thinking and writing enriches our sense of what music means and why it matters, how it’s impacted and been shaped by historical realities and the times we’re living in. This conversation with cultural critic, poet and MacArthur “genius grant” recipient Hanif Abdurraqib is worth the wait. His book A Little Devil in America: Notes in Praise of Black Performance was a National Book Award finalist and the winner of the Gordon Burn prize, and it’s out in paperback this month.

Jewly Hight: Hanif, you’ve said in in other interviews that you initially set out to write a different book, a book about cultural appropriation. At what point did you decide that you wanted this to be a work of celebration, the celebration of Black performance, instead?

Hanif Abdurraqib: I would say about 75 percent through the first draft. You know, the book did not feel to me to be a pleasurable exercise, and I wanted to find pleasure in the work of writing it, because it was an immense undertaking. And I also felt that if I were to focus on appropriation and make this a book centered on stories of appropriation, it would almost by default have to center whiteness, which I wasn’t all that interested in. Instead, I was looking to find a way to center the excitement that I consistently found while just witnessing the realities of performances that had happened. It dawned on me then that the work of the book was perhaps to be a bit more evangelical.

JH: That’s a great way to put it.

Many times when we speak of performance in the context of music, performance is defined in a very specific or narrow way, literally as the notes that are captured by a microphone on the stage or in the studio, something like that. In the book, you take a much broader and richer view of performance. What do you think we gain by expanding our understanding of what all is done for the sake of an audience?

HA: Part of the project of this book was working on my relationship with the word “performative” or the idea of performativity. I’m not thinking about it as only a pejorative. I’m thinking about it instead as something that we’re all engaged in performance at various measures and in various forms and shapes. But it’s not, to me, something shameful. I think it’s something to be in awe of, the fact that we can all weave in and out of performance in this way. And so I really want to write a book that tries to take a very broad approach to defining what performance is and can kind of strip the pejorative nature from the idea of performative.

JH: Your writing also animates the complex dynamic between performers and audiences, and you show how many different ways one ends up shaping the other. You write a lot about the limits of imagination. How do you see the limits of imagination, whether that be of Black audiences, of white audiences, factoring into how performances are received and interpreted?

HA: I think particularly when it comes to Black performers performing in America, those limitations are baked into the American expectation of what Black people are capable of and the multitudinous nature of Black people, not just in their performances but in their living. And so because of that, I think it can create a somewhat challenging atmosphere inside of which people are making work.

The minute an artist creates something and puts it out into the world, it is no longer theirs. And there’s something really vital about letting go of that, I believe. For me, it has been. And part of why I think it’s been important to let go of that is because I understand that I’m operating within limitations and I can’t really make up for the limitations of an audience that maybe doesn’t fully understand where I’m coming from. And so those limitations exist. But I think a big part of maybe circumventing them is just giving yourself over to the fact that you’re going to find your people one way or the other.

JH: In a section where you deal with blackface minstrelsy, you point out that to consume is not the same thing as to love. And obviously there you’re talking about an era that is historical. But how how do you think that that truth also resonates across eras, and even recent times, including the one that we’re living in now?

HA: Right now, I believe that we’re living at a time of distance. You know, we’re so distanced from each other, and this, I’ve noticed, has caused a lot of folks to maybe even heighten that distance between consumption and love, where someone feels as though not only they know you, but that they are owed something of yours because they’ve enjoyed something that you’ve made. And I think it’s important to keep that bridge distinct between consumption and affection, because otherwise I think as creators, you lose sight of why you create, who you’re creating for, what your idea of audience is and what your relationship with audience is. And there’s a potential for you to maybe veer into believing that you owe an audience more than you owe yourself. And that’s certainly not something I believe is true.

JH: When you write about “Soul Train,” you devote several pages to it, but especially to a particular aspect of the show, not the famous musicians and bands and artists that were booked to perform on it, but the less famous dancers in the Soul Train line. Why did your admiration land there?

HA: When I was young and watching “Soul Train” reruns, those were the stars of the show, you know? And there was something fascinating to me about people making the most of a brief window of time in which they are on television. That really fascinated me and excited me. It felt like a thing worth diving into, because there is something really beautiful, I think, about the way that “Soul Train” made it so that everyone had a role in the machinery of the show. And there was a kind of a democratization of excellence where everyone kind of got a slice of it, their own corner of excellence that they could use to, you know, spin their way or dance their way or sing their way into that that beautiful machinery of “Soul Train.” And so it was important for me to highlight the dancers because, for me, the dancers were the constant. They were the thing every week that I would turn to and return to.

JH: When you take up the greatness of Aretha Franklin in your writing, your focus doesn’t only stay on her. You also detail what her return to singing traditional gospel music drew out of those who were present when she recorded her Amazing Grace performances and how she was finally sent home by those who were left behind, who are who are still living. Why did you feel it was important to consider all of that?

HA: I want to specifically, with Aretha, crystallize this moment of her funeral. To watch Aretha Franklin’s funeral play out in a community of of watchers, particularly Black watchers, was funny and interesting and enjoyable, because it was yet another time where it felt like there was a language unfolding that I understood, that so many people I knew and loved understood and that felt like just ours. And there was also a performance in that, the funeral itself. Another thing is I didn’t want to create a world where the funeral itself was only a point of grief and sadness. I don’t think that grief is a single, monolithic feeling. I think that behind grief, there are a lot of really beautiful and fluorescent emotions that are almost a requirement in order for grief to function. And I think the funeral allows for the the honoring of that.

JH: There are passages in the book where you address what people have often sort of fixated on about Merry Clayton, that she seemed closer to tragedy than to to stardom. You offer a different response. You want to give Merry Clayton her roses, her due. Is that kind of a way of you showing us what being an audience member can mean to you?

HA: I think and hope so. But I mostly wanted to create an alternate reality that is still a very real reality, where Merry Clayton is seen as an artist who is more than just a tragic figure. I wanted to attach something beyond tragedy to the life and art of Merry Clayton, who deserves that, who just last year out a brilliant album, you know? I didn’t want to make it seem as though Merry Clayton’s brilliance was something that only existed in the past and was tragic. For me, that’s a requirement of being a thoughtful and generous audience member, is to approach someone in fullness and in generosity and give them the care that their history deserves and their living deserves.

JH: We’re not that many weeks removed from this year’s much talked-about Super Bowl halftime show. You wrote about a different year, the year that Beyoncé appeared during Coldplay’s set and performed “Formation” for the first time and nodded to the Black Panthers with costuming and choreography and all kinds of meaningful gestures. And you write about it like it would, of course, inspire an array of responses that might even seem diametrically opposed to each other. What do you appreciate about how Beyoncé addressed multiple audiences differently and simultaneously in that show?

HA: I tried to be a little clear about the fact that I don’t know if that performance itself was the work of, you know, a revolutionary or a revolutionary act. But I do think perhaps putting those aesthetics on a stage as large as Super Bowl had impacts that, if nothing else, caused discomfort or seemed to cause palpable discomfort for some of the viewers, white viewers, mostly. And there’s something about that the kind of art of agitation that I think is a vital part of Black performance throughout history and kind of seeking ways to reform and reframe oneself as agitator. Even if that’s not the intention, if the intention is just — and I’m not speaking for Beyoncé — the intention is just, “I want to pay homage to my people in any way,” that can be the work of agitation. But it also is turning away from those who might be agitated and saying, “Well, I’m not that interested in what you have to say, although I know that you are going to say something.”

JH: Late in the book, you take us into punk scenes that you’ve moved through. I wonder, what did you learn from reflecting on what you’ve experienced in different rooms, depending on who was on stage, who was in the crowd around you and where you were in your own life and outlook and desires?

HA: As I as I’ve gotten older, I definitely feel like I’ve tried to be more thoughtful about my time on these scenes and how not all the time, but occasionally, I feel like I perhaps did things, not horrifically violent things, but things where it was like in the acts of exclusion that I felt, I would sometimes keep other people out, keep out young women in a way that was gatekeeping — not violently gatekeeping as it was thrust upon me, but still gatekeeping.

As I ran through my early 20s in the punk scene, I’m happy that I corrected a lot of those behaviors, because I think often about the biggest thing that I learned is that to take what is being pushed upon you, and to take the the harm that is inflicted upon you, and then reverse and inflict that harm upon other people who are at a different margin or perhaps more marginalized than you are, that’s really nefarious work. And so any time I spend writing about the punk scene, I’m reflecting on my complicity in that type of gatekeeping and how I grew from it.

JH: You mentioned earlier that you realize once you put a work out into the world, you in some ways relinquish control of it. A Little Devil in America has been out in the world for a year now. It’s about to come out in paperback. I wonder what fruit you have seen grow from it being out in the world, what kinds of conversations you found yourself drawn into, what ways you have seen it matter to people?

HA: Well, one big thing is that the history of the life and story of Ellen Armstrong, the first black woman magician to headline her own show in the United States, has gotten far more attention than it did when I first wrote the book. It was so hard to find anything about her life and story when I set out to write the book. And now there’s a growing catalog of her history that is present on the internet. And that’s really uplifting and exciting for me, because that is the history of someone who I think deserves just a wide range of care and thoughtfulness attended to it. It’s a history that is under-told and underappreciated. And so I am thrilled that of the things that have come out of the book, we’ve gotten a little bit more about Ellen Armstrong in the world.