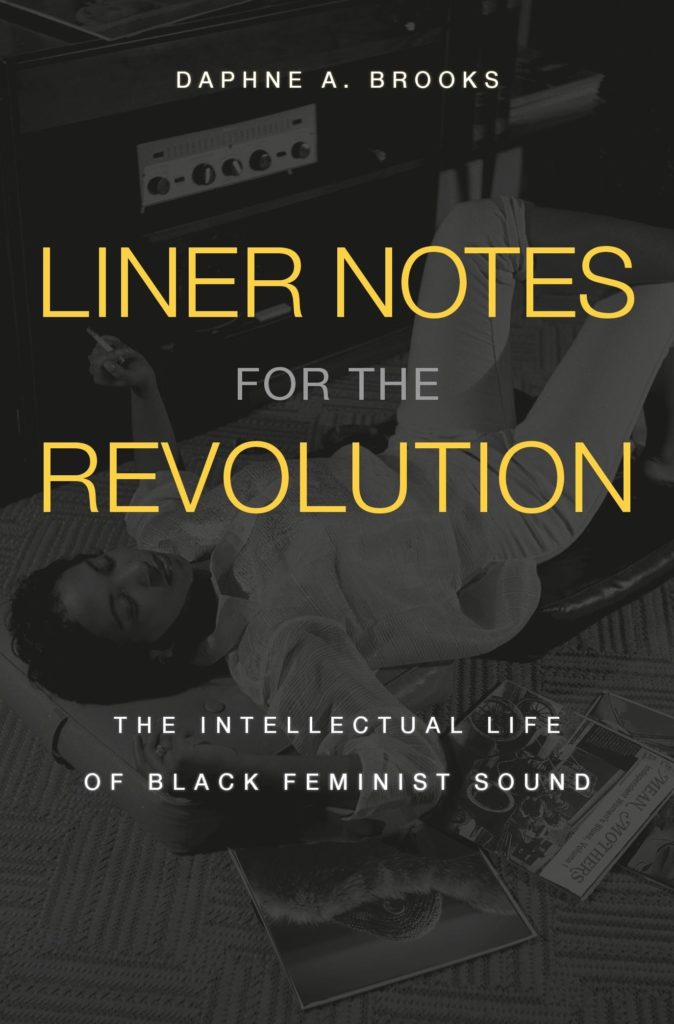

Our latest Culture Club conversation is with critic and scholar Daphne Brooks, author of the stunning new work Liner Notes For the Revolution: The Intellectual Life of Black Feminist Sound. Through close listening, attentive interpretation and poetically pointed critique, she fleshes out an alternative to the narrative of cultural significance that, for the last century, has primarily been written by white men and has seldom taken seriously the music-making, or meaning-making, of Black women, who have mightily shaped the modern world. “Quiet as it’s kept, Black women of sound have a secret,” Brooks writes tantalizingly in her introduction. “Theirs is a history unfolding on other frequencies while the world adores them and yet mishears them, celebrates them and yet ignores them, heralds them and simultaneously devalues them.”

Jewly Hight: In what ways is this book a culmination of your own journey through engaging with music as young listener and collector and later becoming a scholar and critic?

Daphne Brooks: My mother and my father escaped the Jim Crow South in 1950 and moved to, in my opinion, the land of milk and honey, Berkeley, California, even though the West and the North and everywhere has its problems for Black folks. They moved to the Bay Area in 1950, had two kids ahead of me, and then I was the surprise. In 1968, my dad was the first Black principal of a high school in San Francisco and everybody was busy in my household. My mother was a school teacher. There was a lot of music in the household and everybody had their own generational interests. Everybody kind of represented a moment in Black music history across the 20th century, in my dad loving big band and my mom loving Billy Eckstine, and then later the Spinners, and my brother loving the Temptations and my sister being a part of the beginnings of a kind of post-Civil Rights era of school integration, which was deeply traumatic to everybody, but meant that we were exposed to all sorts of music and cultural formations. So my sister was both listening to the Jackson 5 and Barry Manilow.

So that was that was a pretty wide universe, but it did not include the Clash. It did not include the Police. It did not include Prince. When I got my first Walkman, when I was in seventh grade, I asked for 1999 on cassette and heard things that my parents, I know, would have been horrified to know I was listening to and loving and totally captivated by. So that’s kind of the long story of how I ended up using my weekly allowance to get on the bus and ride out to Tower Records. I was drawn to rock music criticism, to that big book section in Tower, and the magazine stand, in part because I was obsessed with Stewart Copeland of the Police. I wanted some kind of copy that could be in conversation with me about the music that I felt passionate about and that nobody in my house understood. So I became a little, informal student of rock music criticism, a little, Black girl, rock music criticism head, who at the same time was inheriting all of this extraordinary Black feminist literary criticism and fiction and poetry from my sister, who’s ten years older than me and had gone off to college and brought all that that stuff home. So that’s how you end up getting this very ethical, beautiful mosh pit of ideas and passions that have now obviously culminated in this very long book that I’ve written.

JH: Since you put the word “revolution” right there in the title, let’s establish what it is that you, and the many voices you’re celebrating, are pushing against, disrupting, defying. What do you see when you conduct a clear-eyed examination of who’s controlled the means of musical production and the dominant narrative, who’s done the framing and interpreting for the first century or so of American recorded popular music?

DB: The way that this story started for me, in terms of how to write it as a scholar, was with the recording of Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues” in 1920. She was the first African-American to record the blues. Most people step back and say, “What could you be talking about? Black folks are the progenitors of the blues.” And yes, they are. But in terms of actually being able to record the blues, it was nearly a decade before Black musicians actually were allowed into the studio in order to lay down tracks defined as blues records, because the label heads—all white, all men—had certain ideas about who could actually make popular music recordings and who was going to buy them.

So if we start just with the industry and the market itself, you’ve got a monochromatic social and intellectual and business public that’s defining what the music should be that’s marketed, how it’s defined and who’s going to actually be able to perform it for the masses. That’s why I felt like it was crucial to be able to go back to that moment when she broke through and to think about what it meant for Black women musicians to have to navigate all of those different structures of representational domination. What did it take aesthetically? What kinds of risks? How do you make yourself legible? How do you make yourself audible to a dominant public that has certain kinds of perceptions of what popular music can and should be? So that’s just one dimension of the story, but it’s the original sin, so to speak, that I like to go back to in thinking about what popular music culture has been for the past century in America and globally.

JH: What effect has that had on the industry, its gate-keeping and honor-conferring institutions, and on the music criticism that exists alongside it in sort of a dialectical relationship? How did such a massive gap grow between Black women’s contributions to the modern musical world and their perpetual marginalization, being underestimated, underappreciated, misread, not taken nearly seriously enough?

DB: You go from having a moment in the 20th century with the birth of rock and roll being really led by these forces like Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Willie Mae Thorton, two figures who have been written about beautifully by my colleagues, Gayle Wald, whose groundbreaking work on Sister Rosetta Tharpe is the reason why she’s in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and Maureen Mahon, who has a great new book on black women and rock and roll called Black Diamond Queens. So you have these foundational figures who are breaking open the form and giving us rock and roll alongside others.

But the class of writers who are, at that point, really doing stylistically innovative work with regards to lifting up the music were also developing certain kinds of attachment to the music, which at least in my arguments, were deeply intimate and affectively passionate about music in which they could either see themselves or project ideas about themselves on to the musicians. That overwhelmingly meant emphasizing manhood, exotic ideas about Black manhood, and about freedom and revolution.

And if you are at the bottom of the social and political totem pole, like Black women have always been in this country, why would that class of writers ever identify with those musicians and what they could represent, in terms of liberatory politics? That’s a kind of philosophical way that I think about it. We haven’t had enough conversations about what it meant for white men writing music criticism; we haven’t held them up as objects of inquiry about their own desires that they interpolated into their writing and who they elevated to the status of being geniuses or being surrogates for all the things that they couldn’t be and wanted to be.

JH: Your framing of Black feminist intellectual life is central to the book. How are you expanding the definition of what ways of engaging with music are considered intellectual labor?

DB: The argument that I always make about my book is step back, take a moment, think about a big sweeping history of Black women in popular music culture, something akin to Greil Marcus’ Mystery Train. If you’re having a hard time coming up with an example of that, that’s what this book is about. It’s not about being the panoramic sweep of all of these women, but it is about the story of why we don’t have that kind of mainstream, conventional, canonical text about the enormous and groundbreaking contributions of Black women musicians across the 20th century.

What I’m suggesting is not that that there haven’t been generations of Black women artists and thinkers who’ve taken it upon themselves to create their own knowledge, to produce their own knowledge, define the value of black women’s artistry in popular music culture. In fact, that’s one of the revolutions that I’m charting. And the book is to suggest that the intellectualism of these artists and thinkers took all sorts of different forms outside of the kinds of legible constructs of rock rags and institutional formations like the Grammy category for best liner notes—that you have all sorts of artists who took it upon themselves to create critical conversations about their music, both through lectures and journal writing and epistolary exchanges with their peers, but also in the music itself, that the music itself can operate as a kind of critical knowledge about their own virtuosic artistry.

JH: There are numerous levels with which one could engage a popular artist, and now movie star, at the level of Janelle Monae. What fascinates you about the mythology, the split personas, the notion of time travel that she’s fleshed out around her music?

DB: I talk about Janelle Monae and tip my hat to all of these wonderful fellow scholars of mine in academia who have swooned over her for a decade-plus now. She is manna from heaven for Black cultural studies scholars and performance studies scholars. I mean, as the kids would say, she gives life through her citational references to Afrofuturism and being deeply literary and historical and also archiving this history of pop music, fantasy and experimentalism, avant garde-ism and masquerade that we can see legible, especially in the glam rock radicalism of David Bowie and everybody around him and moving through, of course, Prince, her mentor.

I wanted to really pay attention to what Janelle Monae is doing as a breakthrough in the 20th century, with regards to revitalizing an interest in masquerade for African-American performers and African-American women performers, that the kind of presumptions about racial authenticity politics, which have straitjacketed generations of Black performers is something that she’s exploding. But, of course, that has also been a part of the genealogy of popular music culture that we don’t pay attention to enough that she’s rooted in, Parliament Funkadelic, even James Brown, the use of spectacle. These are all references, again, in her work and her repertoire, the use of spectacle, of excess, of artifice, where sometimes sly and sometimes overt kinds of announcements and statements that Black artists made in order to call attention to the ability to seize control of their own representational agency—to say, “You don’t get to define me along the axis of blackface minstrelsy.” Which is ultimately the tyranny and terror of blackface minstrelsy and being able to define blackness according to white supremacist imaginaries. So the other end of the spectrum, then, is to think in terms of spectacle and masquerade and being fluid in one’s identity formations.

Janelle Monae really manifests that. Her liner notes are extraordinary, and the extension of the kinds of mythologies and masquerade that have deep sci-fi roots and that stretch across multiple albums. But I also love them because they remind us of the importance of collective collaboration in African-American culture. She’d be the first to say that [of] the Wondaland Arts Collective, with her interlocutors Chuck Lightning and Nate Wonder and Roman GianArthur. These are brothers she met in Atlanta. Chuck and Nate, I know, went to Morehouse and I’ve had a great time talking to them in the past. I taught a class at Princeton where they came and they rolled in with a PowerPoint and, you know, talked about Sartre and Du Bois the whole hour, and Toni Morrison. This is all important just to say that Janelle Monae has been very open about creating art that is communal and that takes shape through dialectical energies and through kinds of communal intimacies.

[Monae’s album liner] notes themselves, which I see as being a product of those collaborations, are about trying to document, “What are the ways that this music that we’ve recorded for you encapsulates all of these kind of collective memories across the 20th century in relation to the art that we love?” It’s beautiful. It’s non-linear, very experimentalist, kind of critical work. And it follows in the vein of people like Sun Ra’s notes and John Coltrane’s notes, but also Frank Zappa’s and even some of Dylan’s infamous and well-known and legendary notes.

JH: I love that you write of Valerie June as an Afrofuturistic roots artist. Reaching back and dreaming forward are often perceived to be contradictory mindsets for an artist. How do you feel like she embodies both impulses?

DB: For Valerie June, one of the things that I was so drawn to in my conversations with her and in listening to her work was how she could anchor her narratives compositionally and lyrically. The stories that she’s telling and these sorts of familiar historic moments of Black vernacular life, be it in the space of her family home or in her communities, there are certain kinds of musical figures within her sound which are very familiar, but they take on a sort of mystical level of enchantment.

And to me there’s a parallelism between what she’s doing and, say, the wondrous MacArthur Fellow scholar whose work has had such an impact on my own, Saidiya Hartman’s scholarship, in which she coined the formulation “critical fabulation” to talk about what it means to actually do a kind of dream work in the archive, to be able to dig up your ancestors and maybe not be able to piece together their stories. Most likely not for Black folks who have limited access to our past because of our subjugated pathways through American culture.

Having these kinds of fragments of history and then being able to dream and imagine and get as close as you can, affectively and empathically, to the traces of what they left behind, formalistically, that’s what you hear Valerie June doing to live in the space of sonic enchantment that holds all those ancestors close to you, but also imagines how you carry them forward into the future. Toni Morrison has shown us this, another fabulously important thinker in my work. If you think about something like her masterpiece Song of Solomon, that’s a bildungsroman about a character, Milkmen Dead, who has to sort of face his past before he can move forward and fly.

JH: Beyonce is a towering global pop figure. How do you conceive of her work, especially Lemonade and the track “Don’t Hurt Yourself” as “cultural arm wrestling,” Black rock reappropriation, a cultural event on par with any that’s considered a standard-setting moment in rock music?

DB: I’ve been arguing for over a decade that we have to think about Beyonce’s work as historically archival, from the different kinds of iconic figures that she’s inhabited in her performances—we don’t have enough time to list them all, but a couple of them would be Tina Turner and Etta James in “Cadillac Records” and even Betty Davis in the Austin Powers sequel, which people forget about, and Diana Ross in “Dreamgirls.” She’s been very historically-minded in her performances, one could say, with an eye towards being able to take on the mantle of that sort of iconicity. But to me, it becomes even clearer what she’s up to in something like Lemonade, which initially was read through a very narrow prism as being about domestic conflict, about “what Jay-Z had did,” but understanding both visually the economy of that of the video narrative and having so many directorial masters that she was working with, in particular, Melina Matsoukas, Black feminist, extraordinary director, who goes on to do “Queen & Slim” and many other projects.

The sonic layerings of Lemonade and a track like “Don’t Hurt Yourself,” which is working at the level of sampling, being able to take these different kinds of samples of cultural history related to Black life. So, think Memphis Minnie’s “When the Levee Breaks,” which is covered by Led Zeppelin, which is then reinterpolated into that particular track, which is also, in part, a collaboration with Jack White, and which is then situated visually within the narrative of Hurricane Katrina and New Orleans, Black life in New Orleans under duress, means that you’re looking at a work that has just such a representational density that it needs to be regarded through a variety of different critical lenses. We’re coming up on the fifth anniversary of Lemonade and we still haven’t fully reckoned with that text, in terms of the historical ground that it broke

Let’s play another parlor game: how many albums that broke that top 40, let alone became a worldwide phenomenon, took as their primary objective inquiry the long, transgenerational story of trauma and resilience and resistance as it was experienced by, wrestled with and reanimated and retold by Black women thinkers and performers, grassroots activists and artists?

JH: Why do you think Rhiannon Giddens should be considered both an important artist and a serious historian?

DB: I think that Rhiannon Giddens reminds us of the ways in which Black artists, if they seize the role, are to a certain extent—maybe this is my argument, rather than hers—but they are always stepping into the role of doing historical work, of pulling on this long and varied and luminous and complicated tradition of sound that was born in the U.S. out of captivity.

The question itself is a fascinating one for me, because whether we’re African-Americans or not, we are all we are all constituted by our history. For Black artists in particular, and African-Americans across the board, if you institutionally don’t have control of historical narratives through all sorts of legible and mainstream forms, such as institutions like museums and historical archives, Library of Congress—you don’t have a National Museum of African-American Culture until very recently—in order to sustain and cultivate a longstanding life world of historical memory for your community, and also more broadly for the country, from an African-American vantage point, you have to take on that role yourself. Most often we know African-Americans resorted to the oral tradition in order to do that work, of course, handed down to them from the West African practices of oral sociality, and oral expression being principal as opposed to being secondary to discursive work.

So that’s a long way of saying that I think that she is stepping into a tradition that already exists, but that because of the forms that she’s so drawn to and that she so beautifully brings back to life for us, be it string band music through her work with the Carolina Chocolate Drops or through her own research chops, being able to excavate archival documents of slaveholders, she’s using her skills, her visionary genius in order to handle all of that historical work through the prism of her virtuosic musicianship.

So the two are completely entangled with one another, and that’s absolutely thrilling. It also means, then, that she’s a public historian, since as a popular musician, she’s able to carry these kinds of debates and questions and ideas that we wrestle with in our classrooms all the time as Black studies and feminist studies scholars and as historians of the U.S. South and beyond, she’s able to take those kinds of questions and root them in music that can reach the greater masses and really demand that those masses think about that history, reckon with that history.

JH: You’ve brought Black feminist critiques and insights into multiple fields, multiple disciplines. Have you witnessed any especially satisfying or constructive moments so far where folks have engaged with your work, where you’ve seen people connecting the dots?

DB: I’m not on social media, so I will just say that I’ve been thrilled to receive word that there are young folks who’ve been moved by the way that I write, folks that are pre-college and also folks who exist outside of the academy, much larger publics than within the academy who feel that my work has an accessibility. That’s a word that they use. And I hope that comes from writing from a place of, deep emotional connection to the cultural objects and narratives that I’m shining a light on in the book.

To bring it back around to what we started out discussing, I’ve learned to do that through the twin forms of both the rock music criticism that I really fought with growing up and the Black feminist theory and practices and literatures, which have always reminded us that the personal is political. To be brave and to be true to the personal and the fact that the personal always informs the ways that we write as a critic, I think has resonated with people.