Linda Martell — the too-long-overlooked, first Black woman to reach the country charts in the early 1970s — reemerged on Cowboy Carter to drop some wisdom on us this year: “Genres are a funny little concept, aren’t they? Yes, they are.” She sounded deeply knowing as she answered her own question, a dignified elder with a history of resisting the forces that would constrict or diminish her creativity.

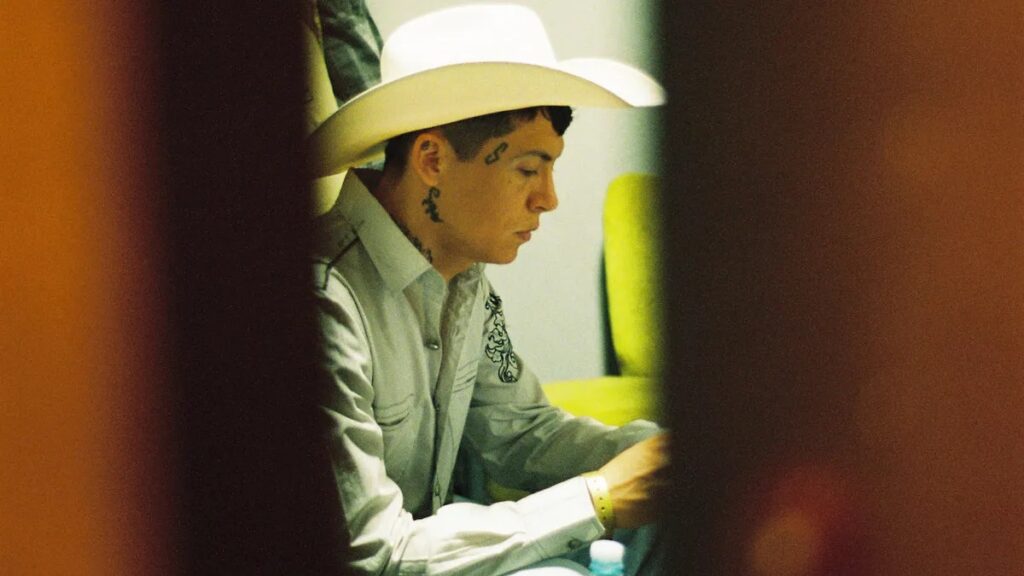

Martell’s spoken intro set the tone for “SPAGHETTI,” a theatrically tough reimagining of cowboy imagery that features bars from Beyoncé and a brooding hook from Shaboozey. When the track dropped in March, it was viewed as a collaboration between a pop superstar sharply broadening the scope of country music and new country talent bubbling up from the hip-hop underground. A lot of elements came together in a less-than-3-minute piece of music that was ultimately nominated for a Grammy for melodic rap performance.

Pop music is an elastic realm where performers who fail to switch it up stylistically risk seeming stagnant. But to some degree, country and roots music operate by different sets of values and more clearly defined genre boundaries, presided over by their own, separate sectors of the industry. The artful mashup of “SPAGHETTI” was emblematic of a year when those types of music combinations attracted stylistic fluidity that was often in conflict with limited notions of who belongs in those categories and communities.

Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter was famously passed over by the CMA Awards, while it’s in serious contention for Grammys in country fields. That’s the difference between judging the work based on how cozy its creator is with the country industry community and assessing it purely on its sonic qualities.

Even the Shaboozey bop that became 2024’s most popular slice of country music, “A Bar Song (Tipsy),” didn’t translate into him truly being treated as a country insider. During the CMAs, both scripted host banter and an acceptance speech included jokes about his moniker that implied the Nigerian American hitmaker — who’s savvily advanced the blending of country and rap that many others have attempted in the format — was some sort of exotic interloper.

I witnessed a stark contrast in the reception received by Post Malone — another pop star, but a white one, venturing into country territory. He was celebrated for faithfully following the genre’s gestures.

It was fascinating to watch how country music’s relationship to Kacey Musgraves evolved this year. She came up in the genre, but was accused of taking a pop detour. And even though her 2024 album Deeper Well had pristine, pastoral folk textures — and there was much discussion about it being recorded not in Nashville, but New York — it was treated as a sort of homecoming. And in interviews, she gave that narrative her casual approval.

“Of course, I get to explore all these other styles,” she told Seth Meyers on his late-night talk show, “but coming back to country always feels like home to me.”

Musgraves’ occasional singing partner Noah Kahan has broken through in pop by hearkening back to how Mumford & Sons galvanized huge audiences with openly emotional folk singalongs, and that’s enabled him to straddle lanes. This year alone, I saw Kahan perform at both the Americana and CMA Awards.

And artists like Amythyst Kiah, Kaia Kater and Sarah Jarosz — who emerged years back as virtuosic pickers in folk and roots circles — explored pop-rock and jazz-pop refinement in the studio with their choices of producers and arrangements.

There was one telling, but under-chronicled trajectory, that I paid particularly close attention to: how Tenille Townes renegotiated her relationship to genre.

Back in the late 2010s, Townes was eager to sign with a major country label and release her debut U.S. single to radio. “Somebody’s Daughter” was a warmhearted singer-songwriter tune meditating on the humanity of an unhoused woman, no less.

Recently, I asked her to reflect back on that moment: “To me, it was such a dream realized to be like, ‘Here’s this music I’m making and here are these people in a really fancy office and suits that believe in it and want to roll some dice on what I’m creating.’”

Townes excelled at relating to fans in the down-to-earth way that country artists are expected to. Musically, though, she stuck with her sensibilities — toggling between observational and confessional postures in her songwriting, and conveying intimate feeling with a singing style as closely related to indie music as country. Never did she affect a twang.

“No matter what different production that we explored through the process of trying music over the past several years, my voice sounds the same,” she said.

After the label declined to release several songs Townes cared about, they parted ways this spring. She told her TikTok followers about it with the elation of someone who’s newly, happily single.

@tenilletownes Entering my freedom era… will you guys come with me? #independentartist

♬ original sound – Tenille Townes

Declaring that deal a poor fit has made her reconsider where to aim her energy. She told me she’s “grown to a place of wanting to make music that has a much wider horizon than what can often be pegged as what fits in country.”

Townes hasn’t completely closed the door on country music, though, because she’s aware that the genre slowly absorbs styles that start out at its margins.

She’s also been watching how singer-songwriters like Kahan and Musgraves bring folk and country leanings to broader audiences.

“What if there are different categories of music lovers who wanna listen to stories and songs and voices and actually don’t care what sticker you put on it?” she mused. “That’s so exciting to me. That’s what has been so inspiring to me about people like Kacey, and especially like Noah. I don’t know what you call it, and it doesn’t matter.”