If you’ve driven down Music Row over the years, you’ve seen streets named for Chet Akins and Roy Acuff, foundational figures in the creation of the country music industry in Nashville. But it’s taken far longer for DeFord Bailey — who preceded them both as the Grand Ole Opry’s original, Black, star performer — to get a road of his own, among other honors.

This Saturday at noon, a street in the heart of the Edgehill neighborhood will be dedicated as DeFord Bailey Avenue, and his descendant Carlos DeFord Bailey has a great deal to do with that.

For the younger Bailey, walking around that area means revisiting youthful memories of family time.

“This is where it all began, right here at the lot you’re standing in,” he says, spreading his arms to encompass the apartment complex, parking lot and grassy rounds at the corner of 12th Avenue South and Edgehill Avenue. “This is where he last resided at, in this high rise here. When he would come down and sit out on the lawn, he had lots of friends, and he would sit there and blow the harmonica for ‘em and everything.”

The rest of the time, the elder Bailey was busy operating his business across the street and half a block down.

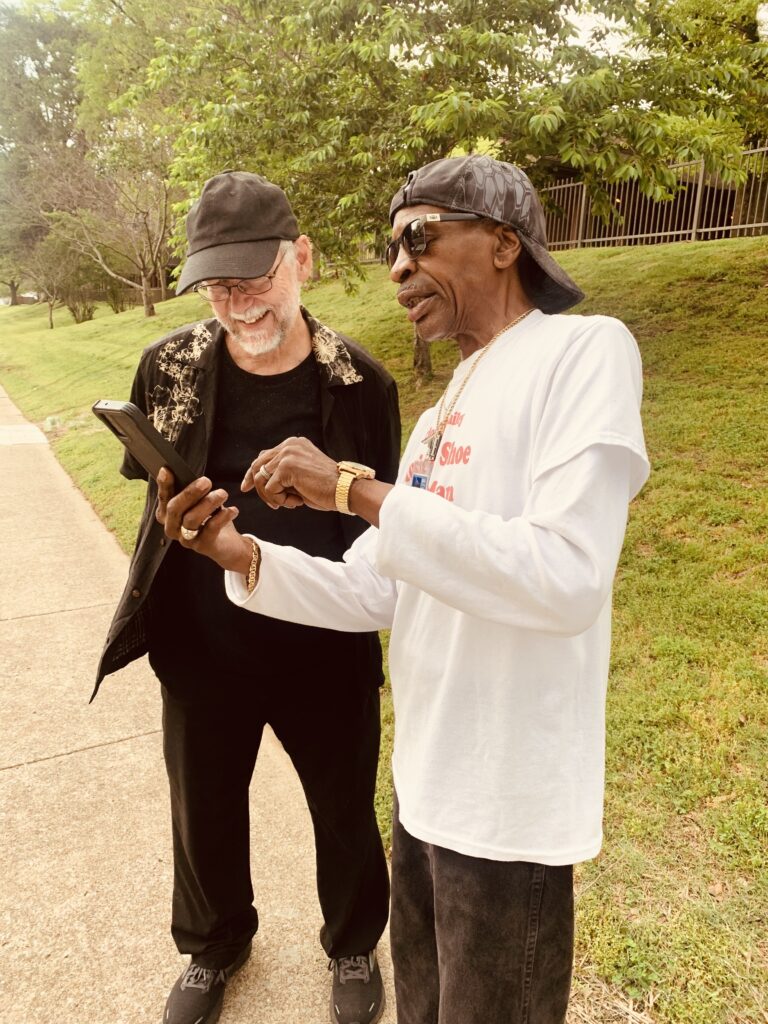

“His shoeshine shop was about right where that building is,” Bailey recalls, pointing at the newly constructed residential complex for veterans, Victory Hall. “And he was open six days a week. And my job was when I showed up was to prep the shoes.”

The younger Bailey dedicated himself to carrying on his grandfather’s legacy. Not only the shoe-polishing part, but the trailblazing country music career that came before it, which is the reason for the historical marker on this corner.

“It says, ‘Bailey, a pioneer of the Grand Ole Opry, its first Black musician, lived in the Edgehill neighborhood for nearly 60 years,’” the younger Bailey reads aloud.

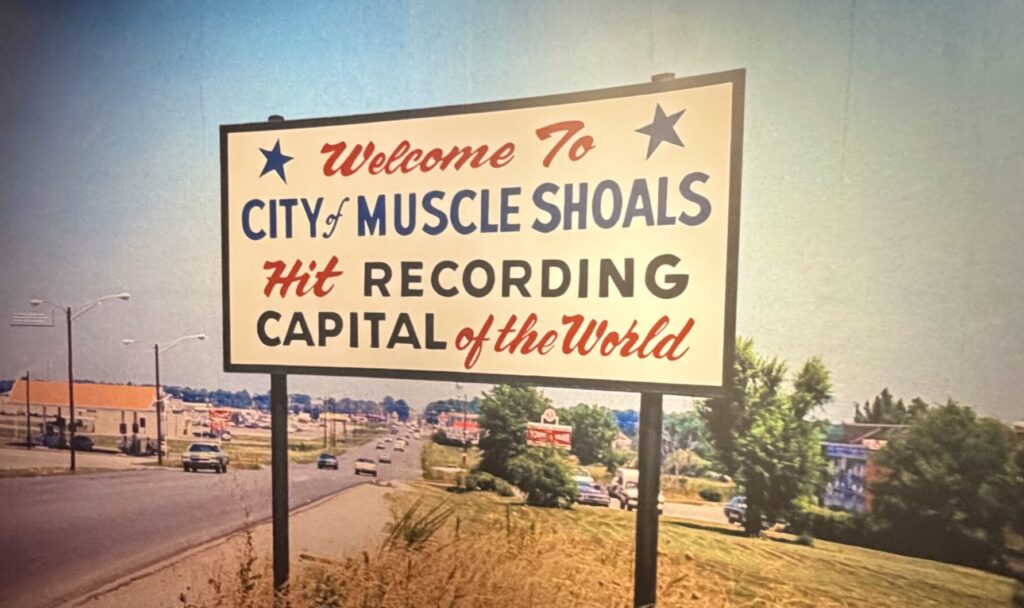

The remaining text lays out another monumental first: no artists had done major recording sessions in Nashville, until DeFord Bailey cut eight sides for RCA Victor in 1928. Since the sign has a finite amount of space, its description of his musical accomplishments, and how he navigated the racial boundaries enforced around genre from those early days of commercial radio and records, is, by necessity, boiled down to the basics.

Nearly a decade after Bailey’s death in 1982, David C. Morton published the definitive book-length account of his life and career, with assistance from country historian Charles K. Wolfe. Reading it gave Carlos DeFord Bailey greater insight into his grandfather’s story, and he resolved to do whatever he could to see him take his rightful place in the pantheon of figures that country music honors as ancestors.

“I was wondering why my granddaddy hadn’t been inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame,” he remembers. “It was bothering me, and that was over 30 years ago.”

Carlos DeFord Bailey and other members of his family began a campaign to correct that, leaning on the work of historians like Morton, who just published an updated edition of his Bailey biography, and later on, neighborhood researcher and preservationist Mark Schlicher. Getting Bailey into the Hall of Fame in 2005 was just the beginning, as far as his grandson was concerned.

He wanted to see one of the neighborhood’s thoroughfares become DeFord Bailey Avenue, and Schlicher, who’d uncovered loads of overlooked information about this historically Black neighborhood while undertaking documentary work on another of its notable residents, sculptor William Edmonson, suggested Horton Avenue.

“The very first transmitter building for WSM Radio was right here along Horton Avenue,” notes Schlicher, who joins the interview as we stroll toward the intersection of Horton and 12th Ave. “And that’s how, for the first 10 years of WSM, the Grand Ole Opry was beamed to the Southeast.”

Schlicher pictures Bailey, who often got around by bicycle, regularly pedaling past the facility that broadcast his Opry performances far and wide. At the same time, Schlicher points out, the harmonica virtuoso regularly received patronizing on-air introductions from WSM announcer George D. Hay, who’d call him “our little mascot.”

As popular as Bailey’s harmonica innovations were with listeners — his ability to coax clear tones from his instrument that few others could, his ear for reimagining the sounds of rural life as complex compositions — that didn’t ensure him equal treatment or lasting opportunity among his white counterparts. His Opry tenure ended in 1941, and the institution publicly apologized for those wrongs just recently, with much encouragement from the band, and Opry member, Old Crow Medicine Show, whose 2022 album also includes a Bailey tribute and who’ve shared the stage with his descendent on numerous occasions. (Francesca Royster’s book Black Country Music: Listening For Revolutions also contributed a rich reconsideration of how the industry constricted Bailey’s imagination and stylistic repertoire.)

This Saturday’s street dedication continues the efforts to recognize Bailey’s importance. From Schlicher’s perspective, that includes: “great appreciation for DeFord Bailey fully as a musician, as a composer and interpreter of music; as a multi-instrumentalist; as a Black man who was navigating his way through a Nashville that was as segregated as South Africa at the height of apartheid, and left us with an incredible musical legacy.”

Thanks to groundwork laid by Bailey’s grandson and others, Schlicher says it took a mere four months for them to go from collecting petition signatures to securing the necessary permission to rechristen Horton Avenue. “When we made this proposal to the city officially, there was no pushback,” Schlicher affirms.

A longtime musician himself, Carlos DeFord Bailey has been rehearsing with his band for Saturday’s concert, and also planning what he’ll pursue next on his grandfather’s behalf.

“I would like to see him have a statue, either on the corner of Horton or uptown somewhere,” he says, surveying the street corner that will soon bear his grandfather’s name, then glancing toward downtown, where famous likenesses greet visitors to the Ryman Auditorium. “I see ‘em everywhere, these legends from the Grand Ole Opry.”

He means the performers whose legendary status was recognized right away, those who weren’t forgotten.