Songwriter Josh Tillman and performer Father John Misty seem to be in constant conflict.

Tillman is Father John Misty. The two are inseparable. But since the project’s beginning, fans have loved to wonder where Tillman ends and Father John Misty begins.

“My whole thing is a therapist’s nightmare. It’s this Bergman-esque psychodrama where this Father John Misty construct really has it out for this Josh Tillman guy who keeps writing increasingly more humiliating songs,” Tillman told me in a rare interview.

Father John Misty’s new album Mahashmashana, which is Sanskrit for “the great cremation pit,” has been universally acclaimed. And once again, Father John Misty is analyzing the nature of truth in the world and within himself.

“I must be convinced that there’s some kind of truth,” Tillman said. “We’ll see when the body of work is finished. We will see what was achieved.”

Back in the early 2000s, Josh Tillman was making earnest indie-folk under his own name, J. Tillman. In 2008 he joined Fleet Foxes at the beginning of their indie rise as their touring drummer and left the band in 2011 to become Father John Misty. His debut album, Fear Fun, met the moment. The record was poignant and sarcastic. The LP itself came with a two-page screed of “quantum theory poetry” that he wrote after dropping acid in Big Sur and dreaming of writing “The Great American novel.”

It hit.

“I had been playing for like 30 people. And then all of a sudden there was sold out venues and stuff. I was very suspicious and freaked out,” he said.

On his second and third records he confidently delivered lines that were more sardonic and, at times, maybe too much, like “bedding Taylor Swift every night inside the Oculus Rift.”

His third album, Pure Comedy, is filled with observations that are as touching as they are funny. Take the opening line to the album:

“The comedy of man starts like this: Our brains are too big for our mothers hips. And so nature, she decided this alternative: We emerge half-formed and hope whoever greets us on the other end is kind enough to fill us in.”

The indie world seems separated on its opinion of Father John Misty. Some claim he’s an arrogant blowhard who takes himself too seriously. Others hold him up as a top-notch entertainer who’s able to speak truth to the world through the charm in his songs.

But who is that man in the songs? Is that Father John Misty, persona and provocateur, or is that Josh Tillman? The interrogation reached a fever pitch from 2017 to 2019 with some big profiles that tilted towards the side of Tillman as arrogant blowhard.

“I certainly had petulant moments where I just didn’t wanna be doing it [press] and that came through…I needed a break. I needed a good seven-year break,” Tillman said. “I will probably never do a big profile where I’d hang out with some guy for three days and let them just trip the light fantastic. That’s not likely to happen again.”

But somehow, we were able to slide this interview by him. “Sometimes my managers just say, ‘Hey you have an interview this afternoon.’”

So, in an effort not to miscategorize, skew or editorialize Tillman, we’re allowing him to speak in his own words. Below is a transcript of our interview, lightly edited for length and clarity.

Justin Barney: I would like to talk about the new album Mahashmashana. You described it as an album that is preoccupied with time and endings, and in listening to it, that is true. Do you see it as a beginning or an end?

Father John Misty: Well, I guess they’re all on the same spectrum. Not to cop out, but, I guess it depends on the day too, which didn’t use to be the case. I used to be fairly well convinced that this was all I was ever going to care about. And as I’ve gotten older and my life has changed and having a family and different priorities and all that, it does feel a little bit more uncertain or precarious.

I think that gave the writing a little more heat this time around.

JB: Are you talking about music as a whole or Father John Misty as a project?

FJM: Music as a whole. But I’m also just like an apple tree who sprouts little ballads of despair. It’s just what I do.

JB: I feel like there’s a part of the album that speaks about art and making it as being the ultimate describer of self. Is that what you see your music as?

FJM: Well, I wouldn’t want to figure myself out, you know?

I don’t really want to become some kind of fixed, known entity. And I don’t think that there’s as much relief in figuring oneself out as maybe it feels like on one side of that process. You know what I mean?

Most of the information that we have about ourselves is just, kind of, junk data.

When we talk about identity, I guess there’s a few different levels. The first being just I am my physical body. I identify with my physical body and with what my senses tell me about myself and about the world, and I have a few key meaningless preferences and a few formative memories, and you kind of use that aggregate to come up with some reliable construct that we can cross index when we’re asking ourselves the tough questions about who we are and what our purpose is.

And I think it’s far more likely that the naked reality of what we are bears very little resemblance to the human drama that largely defines our existence.

In Eastern thought you’re not meant to totally diminish or discredit the physical experience that we’re having, but the perspective is more that we’re born actors onto a stage and the assignment is to liberate your immortal soul. And those two can kind of live harmoniously.

But with your original question, I do hear a lot of artists talk about how music is a form of therapy. I’ve never quite viewed it that way. If anything, music has been a way to exasperate those issues or to make them worse.

I mean, my whole thing is like a therapist’s nightmare, you know?

It’s this Bergman-esque psychodrama where this Father John Misty construct really has it out for this Josh Tillman guy who keeps writing increasingly more humiliating songs.

I get some kind of perverse creative thrill from, you know I really will dial up to 11 aspects of my personality that there may really only be like trace elements of and just see what happen because I have certain preoccupations. I like telling a certain kind of story that has a certain type of perverse humor or bad behavior or humiliation. I must be convinced that there’s some kind of truth.

We’ll see when the body of work is finished. We will see what was achieved by that.

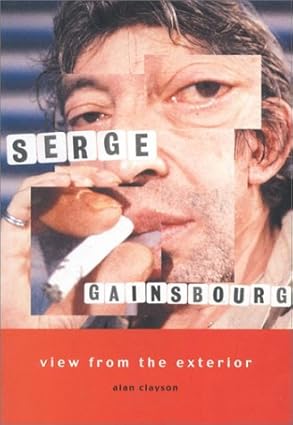

JB: I think it’s the going through it too, you know, and, for me, following along your journey. I want to talk about the, the music of the album, “Josh Tillman in the Accidental Dose.” I remember listening to that for the first time and hearing a Serge Gainsbourg song from that early/mid ‘70s period and none of the reviews mentioned that? I just need to confirm or deny this fact. Is that song in the style of Serge?

FJM: Yeah. I mean it’s the string arrangement definitely is and probably even a little bit in the vocal register. Yeah, it is certainly borrowing quite a bit from Melody Nelson.

But, you know, Serge has one of my favorite quotes about stuff like that, he’s like, “I’ve stolen from everything. I’ve stolen from rock. I’ve stolen from jazz…” et cetera, he’s like, “The important thing is that you steal from the best.”

I’ve never been particularly precious or self-conscious about pastiche. I’ll never be credited as being a great musical innovator.

I was talking to someone, now it just sounds like I’m being defensive about this but I’m really not. Someone was like talking about how you can’t just take preexisting musical forms and then do your own thing over top of it. And I was like, “Well, you just described Bob Dylan.” You know, one of the great originals. I think originality is pretty ephemeral. It’s hard to describe, but easy to identify.

JB: Yeah.

FJM: Just quickly back to Serge Gainsbourg. I just got a new book of English translations of his songs. You know that the guy is a provocateur, et cetera, right?

Some of these lyrics just blow your damn hair back. Especially on the View From the Exterior record and that song in particular is twisted.

JB: In “Mental Health” there’s a good amount of piano in that. As you were talking about the orchestration before and saying you’re not an innovator, I think that you are not giving yourself credit. I remember hearing “Bored in the USA” and feeling like I’d never heard anything like it. Anyways, I was talking to a piano player here the other day and they said that songwriters start a song two ways, on the guitar or on the piano. Which do you start on?

FJM: It’s about half and half. I’d say most of my songwriting happens away from an instrument at this point. My favorite time to write songs used to be in the five- minute window when Em and I were going out for the evening. You know, I would be ready to go and then I’d have like five minutes while she was getting ready. For some reason there was something in that. It was so low stakes. In those time periods that I started and finished a lot of songs in those little windows.

JB: Where it’s like you’re preoccupied with something else. Little deadline.

FJM: Yeah. I had an office for a few years back in like 2018 or so and I just hated it.

I don’t like the formality. I wrote most of the songs for Chloe at a junk desk leaning up against my in-laws Tuff Shed in the backyard. That was just kind of a magic spot for me.

JB: That’s a fun image. I feel like lyrically there’s so often a joke embedded in the song. Do you lead with the joke? “In the panopticon?”

FJM: Yeah. I mean that line. That lyric and the melody emerged in a discarnate voice in my head, and I just thought, “This has to be the first line to a song,” then it’s a matter of figuring out what a song that starts with that line is about.

I do spend a lot of time, a lot of fruitless time, sort of under the hood of what makes immortal songs work. Just at a total loss for how to import that into what I do.

JB: What have you found under that hood?

FJM:, On the last record there was a song called “Kiss Me” which was a real deliberate attempt to make something unmediated by me and my criteria for what makes a “me” song.

If I found anything through that experience, it was just how totally uncomfortable a song without any kind of lyrical indicator that I am in on the whole enterprise made me. Just sweating while I was playing that song, but that discomfort was sort of the price for admission, for making something beautiful and unmediated.

JB: You described “Screamland” as a worship song. What are you worshiping there?

FJM: Well. I think that’s like saying “It’s a rock and roll song, so what are you rocking and what are you rolling?”

JB: That’s such a good answer. That’s so funny. In “Screamland” you say that “love must find a way.” To me it’s a bit of a contrast with Honeybear which is largely unsentimental about love, though it is an extremely loving album. Have you found yourself to be more sentimental?

FJM: I guess I reject the premise of the of the question.

I mean, I think Honeybear is pretty sentimental. I mean saying like, “Everything is fine. Don’t give into despair ’cause I love you” is pretty lateral.

JB: That’s fair.

FJM: That line, “Love must find a way. After every desperate measure, just a miracle will take.” I mean, that’s pretty unsentimental. That’s saying like, “We’ve tried absolutely everything, so we may as well try love now.”

JB: I didn’t think of it that way. Yeah. I guess that’s ruthless.

JB: You know, before this album and for a while, you kind of like took a break from everything. Why’d you do that and why’d you come back?

FJM: Um, well you mean from press and stuff?

JB: Yeah.

FJM: I, I just wasn’t enjoying it. I think I was pretty frustrated. And I just felt like I am not the person who should be out here promoting. I’m not a good pitch man for these records.

And it also just became a foregone conclusion that I was this antagonist to the press. Which I don’t know, I think if you were to go back and actually check the record, I’m not sure how totally true that was, but, it felt like I was kind of going uphill against a certain.

JB: I felt that perception.

FJM: I certainly had petulant moments where I just didn’t wanna be doing it and that came through.

I mean it’s a long, charged sort of answer, but I needed a break. I needed a good, um, seven year break.

JB: I think you were being misunderstood.

FJM: Yeah. I mean, it’s not really mine to say. I did notice sort of an increasingly widened gap between what all I had said to a journalist and the finished product.

After a few of those, you start to go like, well, this is totally at cross purposes with what this is all supposed to be about. So, game over.

JB: But now you’re feeling a little better about that?

FJM: Um, you know, I mean, I don’t feel as like life and death, about all of it.

And sometimes my managers just sneak ’em by me. They’ll just be like, “Hey, you got an interview this afternoon…”

JB: …and here we are.

FJM: Yeah. I mean, I think I only did two podcasts for this for this album.

I will probably never do a big profile where I’d hang out with some guy for three days and let them just trip the light fantastic. That’s not likely to happen again.

JB: Fair.

FJM: Despite the last 30 minutes, I don’t really like talking about myself. That was part of the problem. I just felt really defensive. And that that is what came through. That defensiveness and discomfort came through as something quite unpleasant.

JB: Defensive of what?

FJM: Well, I, like a lot of people in show business struggle with a certain dysmorphia around self-worth.

And I mean, for years I was like really convinced that people had come to the show all to see me fall on my face.

Especially early on. It was so disorienting. I was like 10 years in the game by that point and I had been playing for like 30 people. And then all of a sudden there was sold out venues and stuff. I was very suspicious and freaked out.

Why I’m more willing to do this kind of stuff now or feel more comfortable is that I’ve had time to grow up a little bit.

JB: Fair. What do you think about the Kendrick coincidence?

FJM: *laughs* I mean it’s probably pretty over-reported, but it’s quite funny. Him releasing on my release day was just kind of the perfect way to find this thread going all the way back.

It would be one thing if it was like every three years or something. But it’s happening in like a Fibonacci’s number kind of prime sequence.

JB: Even the re-release.

FJM: Pretty funny. Yeah, that was great.

JB: Do you think that he is aware of it?

FJM: No, no, no. Not, not even close.

JB: It’s not because you bumped him at Coachella.

FJM: No. No, but you know, good company.

JB: You know, I saw you when you were playing in front of 30 people at the High Noon Saloon in Madison, Wisconsin. I think the shows are great.

FJM: Yeah, well, I love being on…you know, I love doing it.

JB: You’re so good in front of a crowd.

FJM: Thanks. Well, yeah, I mean, that’s probably its own form of mental illness.

But I do love doing it and I’m glad that I’ve made it to a place where it isn’t like so fraught or ambivalent of an experience…most nights.