The sixth graders who’d been ushered into the echoey cafeteria of Antioch Middle School for a special presentation from 2’LiveBre probably wouldn’t have picked up on the slight raggedness in his voice if he hadn’t brought it up. He wanted them to know that he had good reason to be hoarse — late nights filming a music video with Juvenile and partying with Post Malone — but still wanted to show up for them.

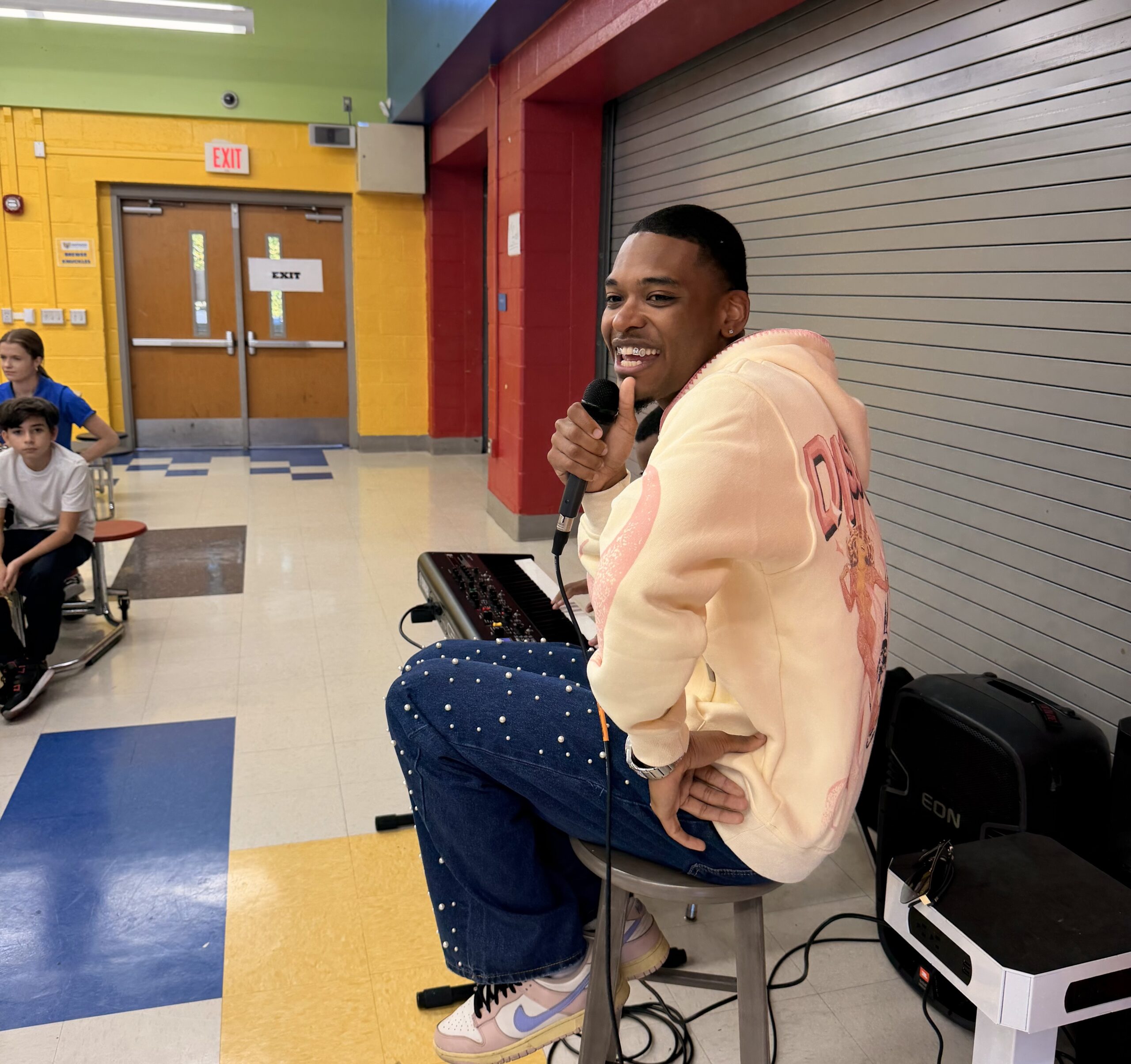

Bre performed some of his school-safe material for the students, accompanied by keyboard player TeAndre Holmes, and left a few minutes for a Q&A. “Just don’t ask me nothing crazy,” Bre cautioned with a sly grin.

One kid wanted to know how much a hip-hop artist earns. Others asked for Bre’s Tiktok handle, and angled for a shout-out in one of his songs.

But what he really wanted to impress on them was that taking their ambitions seriously, and their friends’ ambitions, too, makes a difference. He was living proof that a kid from where they’re from could make good. A ubiquitous presence at cultural events all over his city, he’s demanding respect from New York and Music Row executives alike, not only for his own charisma, hustle and dynamic, drawled bars, but for Nashville hip-hop period. Everywhere he goes, he champions his community.

“I actually was here when I was 12 or 13 at the Boys & Girls club,” Bre told them, leaning back on his stool. “That’s where I started my dream, so to be here in front of the future — ‘cause I know y’all got dreams — I’m grateful for it.”

He first gave rapping a try because a friend swiped his journal, skimmed the lyric-style writing it held and hyped him up.

Hometown hero status came early

Back then, in the early 2010s, he went by Lil Bre, and he was struggling to reconcile two different ways of growing up. “My dad had a lot of street adversity,” he recalled in an interview. “That’s all he had around him in North Nashville. And you had to embrace how to make it out.”

Bre witnessed sobering realities, like “gang activity, violence, people dying.”

But when he stayed with his mom, he said, he had to “code shift.”

“I had to change into what my mom wants me to be. She wanted me to be the kid that’s going to school, making good grades, and smiling, buttoned-up, going to church on Sunday.”

In music, Bre found a path of his own. He had a mentor named Wesley Crutcher who filmed his music videos and introduced him to pillars of the local hip-hop scene, and he also took notes on how teen rappers like Soulja Boy blew up. Before long, the content Bre uploaded to YouTube and the appearances he made at parties all over town gave him a taste of hometown hero status.

His mom got clued into his local popularity when her co-workers asked to hire him to play their daughters’ birthday parties. His younger relatives were already well aware, and hoped some of his cred would rub off on them: “ ‘Yo, take a picture with me so I can prove that you’re my cousin.’”

‘I wanna take over this campus’

Bre got to open for Southern hip-hop stars like Webbie when they came through town. He was tempted to embrace the touring life himself straight out of high school, but instead enrolled at Tennessee State and got to work building his audience on campus. That’s when he reinvented himself as 2’LiveBre.

“My first two weeks somebody asked me to be a Kappa and I started doing parties with the Kappas,” he recalled. Ultimately, he concluded that joining that fraternity, or any other, would be too limiting. “I wanna take over this campus. I wanna be cool with everyone.”

Professors in TSU’s mass comm department took note of how he blanketed their building with flyers promoting his singles, and made him into a class project. The assignment? “‘If we were marketing Bre’s next single, how will we do it?’”

‘It woke me up’

He got permission from the dean to miss classes and compete on the first season of the Netflix hip-hop competition “Rhythm & Flow.” And even though he didn’t win, the show boosted his national profile. He tried to capitalize by playing anywhere he had new fans, only to see that momentum interrupted by the COVID shutdown.

Bre found himself processing that whiplash, along with other life-altering experiences. By then, he’d lost his best friend, and DJ, to gun violence; he’d witnessed soul-baring artists move audiences to tears and he decided he wanted his own music to feel more meaningful. He was also about to become a father. He started seeing a therapist, and channeled his investment in self-actualization into a midtempo number called “Butterfly” that reflected his new mindset: “I’m like, ‘I got a story. I’ve been around all these things.’ It woke me up.”

That’s when Bre started reinvesting in his community through his Butterfly Nation programs. One goal was to boost other artists in Nashville’s hip-hop and R&B scenes. Another was to help kids who’ve done time in juvenile detention find their voices through music. Those who sign on get Saturday studio time with Bre and others in his circle. One success story student, he shared proudly, even opened a show for him.

“I look at myself when I see these kids,” he said. “I didn’t have nobody to talk to, period. Music was everything for me to express myself.”

Insisting on a seat at the table

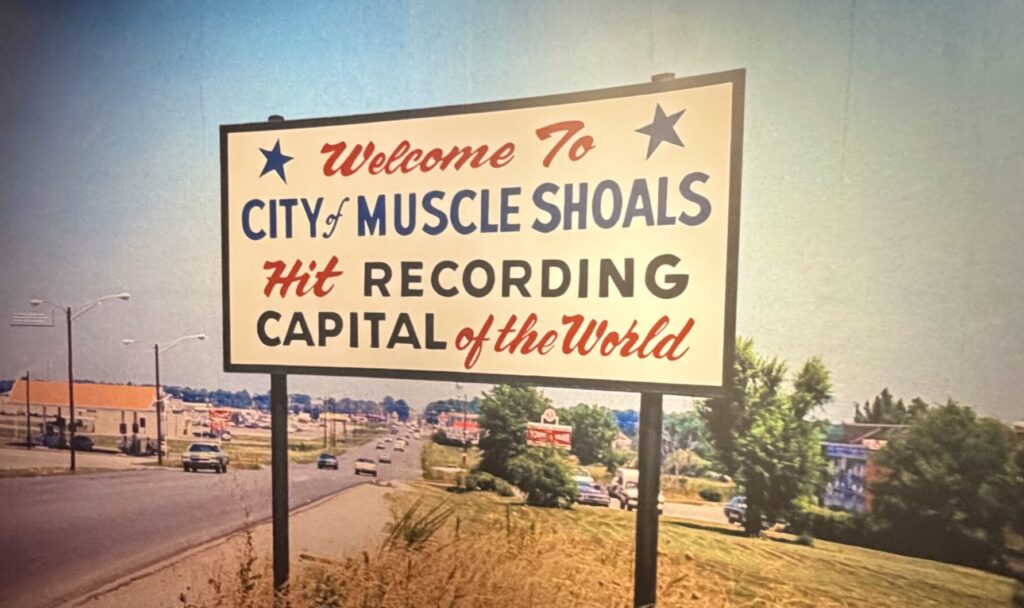

At this point, Bre has been a fixture in Nashville’s hip-hop scene for just over half his life, and for most of that time, the music industry infrastructure of his own city seemed completely inaccessible and its barriers towering.

But he’s operating with a belief that breakthroughs are possible, and his primary strategy is showing up.

Bre invited Daisha McBride and Tim Gent — two artists he’s seen working as diligently as he is to launch hip-hop careers from Nashville — to play a triumphant hometown show as triple co-headliners.

This year, he also signed with well-connected managers based in New York and New Orleans, eager to make the most of the partnership. That’s led to numerous meetings with record labels flush in rap and pop success, and even some with Nashville companies whose country-centric business models Bre felt shut out of, until very recently.

And though he’d always thought country producers were out of reach and, just as importantly, out of budget, he’s hooked up with some that are helping him explore his country side.

“That is when I feel like, ‘Dang, I actually belong in the building here,’” Bre reflected. “‘Cause a lot of those artists feel like this is our hometown and we can’t even say hello to them people. And I’m breaking some ice today.”