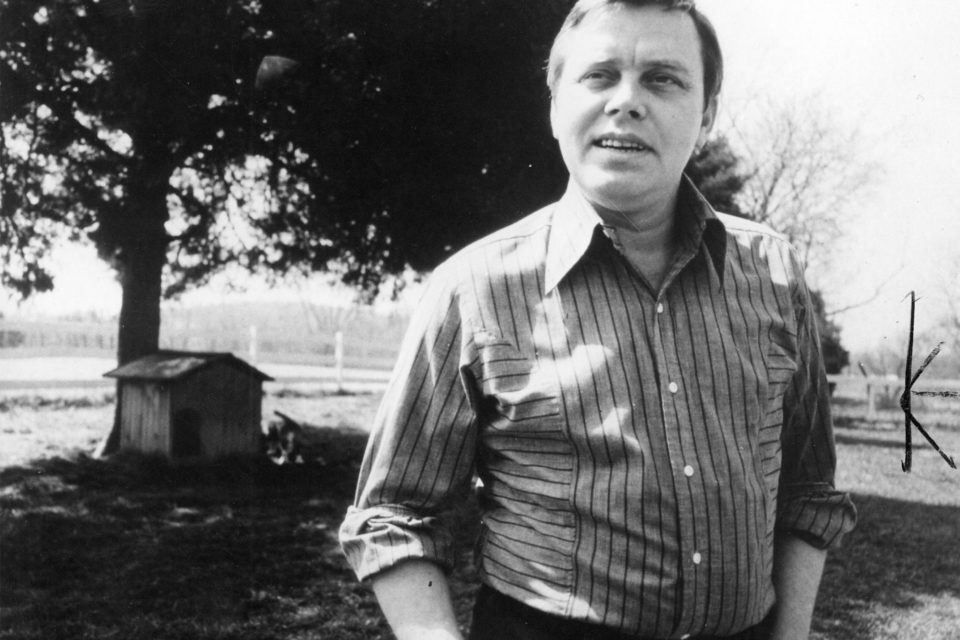

“I don’t like to talk down to children,” Tom T. Hall told me over a decade ago. He didn’t condescend to me either, even though I was a young, somewhat green interviewer back then, probably overreaching in the questions I asked on the two occasions when he welcomed me into the studio behind his home, and he was a beloved and revered Country Music Hall of Famer. From the mid-1960s, when first started working as a songwriter, until he died Aug. 20 at the age of 85, he was never one to talk down to an audience.

By the time I sat down with Hall, he’d arrived at a way of telling his origin story that felt like a pleasing yarn, a tale that tethered his intellectual ambitions down to earth.

He’d begun his life in the Appalachian foothills of northeastern Kentucky on hard labor, heavy reading and bluegrass band-leading; he joined the Army so that he could go to college on the GI Bill. He arrived in Nashville in 1964, still looking quite regimented with his flat-top hairstyle, he noted, but drawn to individuality in his thinking.

“I used to get up in the morning and put a sneaker on top of my head,” Hall claimed, taking thoughtful pauses as he parceled out complete paragraphs with his craggy, twinkling delivery, “and I’d sit there with a sneaker on my head drinking coffee — smoking a cigarette in those days — and I’m thinking, ‘I wonder how many people in Nashville are sitting on the edge of their bed, drinking coffee, smoking a cigarette with a sneaker on top of their head. Probably not very many, so I must be a very unique person. So therefore I have a license to write a very unique song.’ That’ll give you some idea of my thought process.”

At the time, country artists were cutting what he called “little darlin’ songs,” tunes fairly formulaic in their depiction of romance, and he didn’t feel like he could do much with that form. “I wanted to be a writer,” he said, “the Great American Novelist.” He followed those inclinations into story-song territory and submitted the results to the publisher who paid him 50 bucks a week, and received a warning: “‘You better get off that stuff and write some real songs.'”

Still, Hall persisted in writing about what he considered to be real. One of those efforts, “Harper Valley PTA,” about a swinging, single mom taking on small-town hypocrisy, made a star out of newcomer Jeannie C. Riley. Several others got recorded, too, but Hall was advised that plenty of songs he came up with — including “A Week in a Country Jail,” his wryly scaled-down and autobiographical response to an established star’s request for a prison song — were doomed to go unrecorded and unheard if he didn’t get them on tape himself. So to hear him tell it, he reluctantly backed his way into cutting his debut album, Ballad of Forty Dollars, with producer Jerry Kennedy in 1969. “Of course the way the business worked,” Hall marveled slyly, “they put out a single. It went to the top 10, or something like that. And I said ‘Whoa, I’m a recording artist.'”

Hall emerged as a kind of recording artist that was still novel in country music: the singer-songwriter as entertainer. The folk revival was cresting and the wave of country singer-songwriters was coming; it would famously also include Kris Kristofferson, who was just about a year behind Hall. But before them, “singer” and “songwriter” were largely treated as separate gigs in Nashville, and the performers who did pen their own material didn’t make their authorship as big of a big focal point. What mattered most in country music was that singers sounded like they knew what they were singing about — like they could’ve lived it.

The new persona that Hall fleshed out so remarkably was that of the trustworthy observer, a figure who befriended his listeners as a witness to life’s humble and revealing moments (and whose third album was, in fact, titled I Witness Life), who could supply all the detail they needed to get the sense of the situation in three minutes flat, and then warmly put those verses across (he never feared leaving out a chorus). The nickname Hall earned, “The Storyteller,” only seems generic now because it’s a role we’re accustomed to so many country performers trying to claim for themselves. But anytime I hear anyone invoke the hoary ideal that country music is meant to tell stories about real things, Hall’s influence isn’t far from my mind.

He was fond of marking out the philosophical boundaries that he imposed on his role. “I never made judgments in my songs,” he explained to me, repeating an idea he’d expressed similarly on many other occasions. “I had a lot of good characters, a lot of bad characters. But I never bragged on the good guys and I never condemned the losers.”

What Hall did do was make judgment calls, or writerly decisions, about where to aim his attention. He depicted the act of noticing. It’s right there in so many of his song lyrics. In “(Old Dogs, Children and) Watermelon Wine,” he let us know that the speaker “copied down that line” of lived wisdom he heard from a Black man in a bar who was getting up in age. “As I sit here and drink and look for a song,” he inserted toward the end of “The Fallen Woman,” a portrait of a waitress’ weathered self-reliance, “I think I just found me one.” And during “It Sure Can Get Cold In Des Moines,” the speaker in the song, a touring musician subsisting on gin in a motel lounge, spotted a young woman enduring private hardship as he “looked ’round the room, as a tourist would do.”

A line like that is a significant acknowledgement; the narrator’s perspective is confined to what he can see from where he sits. He’s just a tourist, watching from a slight remove, and, Hall knew, could easily turn into an intruder.

Hall opened up space for his audiences to register the particulars of perspective. Whether he’d road-tripped in the name of reconnaissance, a thing he and his wife Dixie eventually did together, mined memories of his working-class early life, or gathered ideas and impressions some other way, whether the “I” in the lyrics seemed likely to be him or someone else, he gave the vantage point a certain heft. In “Ballad of Forty Dollars,” Hall memorably laid out the resentful inner dialogue of a grave-digger owed a debt by the deceased, while in “The Little Lady Preacher” he took listeners inside the lustful but pious mine of a Pentecostal doghouse bassist.

Hall wasn’t one to present a character as a tragic figure. That would’ve been too reductive for him. When he wrote about a washed-up, alcoholic guitarist in “The Year That Clayton Delaney Died” and a young soldier who returned from war without the use of his legs in “Mama Bake a Pie (Daddy Kill a Chicken),” they weren’t objects of pity. He hinted at their outlooks, gestured toward their ways of dealing, and made them multi-dimensional.

Toward the end of the first of my two interviews with Hall, I asked him about “Me and Jesus,” a song that’s something of an anomaly in his catalog; first because it’s gospel, partly sung in collective voice, and second because it starts with a refrain. Its lyrics are thoroughly anti-materialistic and don’t sew things up neatly.

“There’s a line in there that says, ‘We can’t afford any fancy preaching,'” Hall reminded me. “There’s some people who are too poor to show up every Sunday at church. They don’t have any transportation. They don’t have any clothes.” Though his father was a Baptist preacher, he pointed out, he’d figured out on his own by age nine that enlightenment is no respecter of hierarchy: “You can spend ten minutes under a tree and know as much about the universe as anybody on the planet.” Though Hall’s humanism tended to find its most consistent expression in songs depicting men we may presume to be white (he specified on a few occasions when they weren’t), he certainly helped lay groundwork upon which the particularity of other kinds of subjects and other kinds of songwriters hold weight.

“Me and Jesus” has a fuller sound than many of Hall’s recordings, since it features a neighboring church choir that he and Dixie befriended, but his singing on the song is familiarly his — a bit inelastic even on those bluesy, bent notes. Hall’s delivery always had a kindly modesty to it, and it was showcased well on the albums he churned out nearly two a year during the ’70s, a pace that slowed to one a year during the first half of the ’80s. Hall sounded proud of the fact that Jerry Kennedy, his longtime producer, seldom brought in fiddle, steel or twangy electric guitar on his sessions, instruments that were then relied on to supply so much melodrama and muscle in Nashville. Instead, Hall’s songs and singing got a handsomely understated, downhome treatment from first-call pickers. He stopped recording and touring in the ’90s, but finding a latter-day writing partner in Dixie, he kept on with his storytelling. As he reflected to me, “That there is such a thing as a Tom T. Hall song, that was my greatest compliment.”

9(mda2nzqwotg1mdeyotc4nzi2mzjmnmzlza001))