Maya Hawke the daughter of Ethan Hawke and Uma Thurman and a lead actress in Stranger Things, but more than that she is a poet. It’s evident in her new album “Moss.” The first single was “Thérèse” a cultural commentary about a Balthus painting from 1938 that hangs in the Met and is a favorite of hers. In “Sweet Tooth” she tells her mom that she would lie to the accountant if it came down to it. I met up with her at Easy Eye Sound on a hot day in Nashville. She was enthusiastic and earnest. At times she tripped over her words she was so eager to get them out. Stopping at one point to say, “Am I talking too fast?” She was kind, genuine and bursting with ideas. Maya Hawke, the poet.

Hi, my name is Maya Hawke and we’re in a studio in Nashville surrounded by long hanging velvet chandeliers, dark blue couches and fridges full of soda.

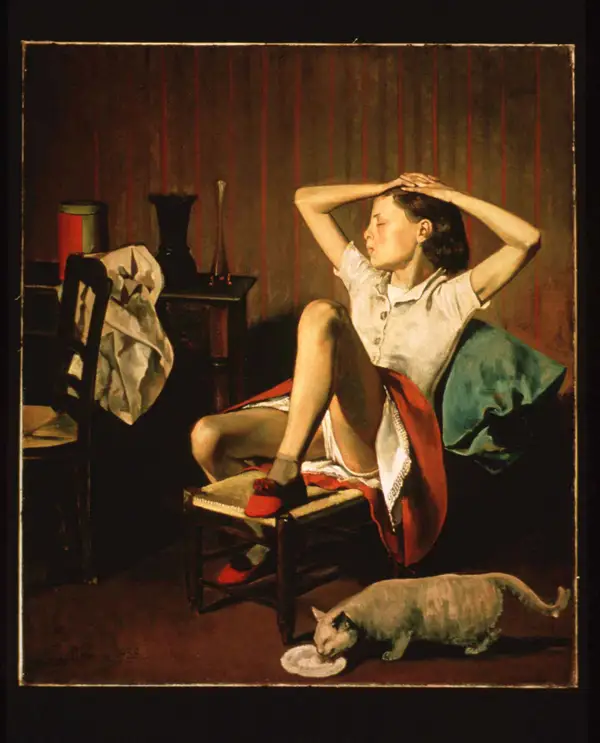

Justin Barney: I love art commenting on art. Could you could you explain the painting “Thérèse Dreaming?” So that we can understand the song “Thérèse.”

Maya Hawke: It’s a painting at the Met by Balthus. It’s of a young girl kind of reclined on a chaise lounge, looking up at the ceiling with her hands behind her head and in sort of what seems like a private bedroom area.

I always love the painting since I was a little kid. Because so many of the paintings at the Met, which up in New York City, so I would go all the time on school trips and with my parents, and it was just like something that we would do. And so much of the paintings there, I didn’t relate to the characters in the painting. Like they were on this this beautiful hilltop. Or they were swinging on a swing with their dress flowing in the wind with these big corsets. But my favorite wing is the classical painting wing. And Thérèse was the kind of character in the classical painting wing that I could relate to as a kid. She seemed so kind of unencumbered and like she didn’t know she was being looked at and free and unselfconscious. It always meant a lot to me.

Then I heard about that there was this scandal. I mean, scandal is a strong word, a minor scuffle that people thought that the painting should be taken down because the way in which Balthus this might have achieved that image. I don’t even really understand the whole thing. But that he might have had a kind of like inappropriate, voyeuristic eye on this young woman while making the painting. And I am totally on that side of, ooh, maybe that was creepy. Creepy is bad. But I had never, as a kid and as an adult, even thought about the painter of that painting. I thought about the person in the painting. And the way the character spoke to me. Maybe a very juvenile way. Like, I think that when you’re a kid and you watch movies, you don’t think about the actors playing the characters or the director or, you know, all the other pieces that go into making it. The characters feel real. And that’s how I responded to visual art and paintings was I wasn’t thinking about the painter, I was thinking about the characters. And I felt sad that this character that I loved and made me feel seen and free and unselfconscious, like I said, maybe was negative because of the guy who captured it. I don’t know, it just gave me a lot of complicated feelings. So that’s kind of the broad strokes of what the painting is and why I started writing about it.

I also wanted to say, based on what you said before about art about art that I was really lucky. I went to a super hippie dippy high school. I got to take this class about interdisciplinary art. What we would basically do is we would come in and there would be either a poem or a painting or some kind of art piece that someone else had made. And all the students would have to sit down and make art about the art piece in a different form. So if it was a painting, we would write a poem about it. If it was a poem, we would make a painting of it. If it was a song, maybe we would make a like, I don’t know, like a collage. It was a very cool class that really opened my mind and got me really into like tabuleau vivantes and interdisciplinary art forms. And it feels like it’s really heavily influenced the way that I live my life as a creator. And it super influenced this song.

JB: What is a tabuleau vivant?

MH: Oh, it’s when you act out a painting. So like, for example, people do it all the time in the Last Supper. That painting of Christ at the at the dinner table. And you get everyone dressed up like all the characters in the paintings, and you have them sit still or move within the structure of the painting as a live action image.

JB: That obviously has a big influence on the song.

MH: So I was I’ve been thinking about this for a long time. For a song I put out a million years ago called “Blue Hippo,” the music video for that I did a tableau vivant of Thérèse and dressed up as her and like got inside the painting.

Then I was I couldn’t stop thinking about her. And so then I wrote the lyrics to Thérèse and I sent them to Benjamin Lazar Davis, who’s in the other room making cool side chains. And, and he sent me back the music to Thérèse. And that’s sort of how it started.

JB: Sweet Tooth just came out and I love your writing. There are so many details in it that are so vivid. I’m going to ask you about some. Like, you are talking about your mom and you say, “I’d lie to the accountant if she wants.” Where does that line come from?

MH: You know, in our life, we have all of these different kind of relationships and all this history. And I think that when you’re I think a part of what the song is about as a whole is like figuring out a way to take on your family’s history and to carve out your own relationships at the same time. I was a teacher’s pet and I was kind of a parents pet too. Like more than I had a lot of friends growing up. I was like friends with my parents friends. And friends with my parents. I think partly because they worked a lot and they were divorced and so all the time was very precious. And so when the time was available, I was sort of always there and I wanted to stay up all night and talk to their friends. Then you start to carve out your own relationships as an adult. But they’re still shrouded in the relationships that your parents have. And as those relationships change, you have to decide if your relationships change and how impacted your view of people is by your parents or like other people’s view of those people in your life. So I think that comes from that feeling of being like, Oh, I’ll do whatever, I’ll do whatever you want. Like I just like, yeah, do whatever you want.

JB: Do you think that, that wanting to spend time with your parents is because probably so many other people wanted to spend time with their parents?

MH: God, no, no, no. That really was not a big part of my life. Any kind of awareness of that. I really I think it was just about the time shortage. Between everyone’s work schedules and the divorce there was a supply and demand issue.

JB: So you say, “I saw a movie that everybody hated in Duluth.” And of course, I’m thinking, what is that movie?

MH: Oh, it’s “Tenet.” I mean, I’m so sorry to the people involved in the making of Tenet for telling them that everyone hated it. But, I really loved “Tenet.” It was the first movie that I went back to the theaters to see after the pandemic, and it was just me and my brother alone in Duluth, Georgia. In this big AMC multiplex in like the perfect seats, completely alone watching Tenet. And maybe we’d smoked a little weed or something and it was just the greatest movie we’d ever seen. We were freaking out. I loved that movie.

JB: And you talk about having a sweet tooth. What is your favorite sweet?

MH: It’s funny. I don’t even really have that big a sweet tooth for sweets. I mean, I love Sour Patch Kids. I go crazy for the gummy candies. But to me, it’s that’s more of a metaphor about, like, loving the good things of life so much that it hurts you a little bit maybe. Like being a joy monger so much that you might lose the appetite for putting up with things that are less fun. And life is a lot about things that are less fun. Like relationships are about moments that are less fun. Work are about moments that are less fun. And and then there are these beautiful, great moments. But I think that the sweet tooth is more of a metaphor about struggling with the part of me that just wants to skip from beautiful, great moment to beautiful, great moment with none of the boring bits in between.

But if you do that for too long, you don’t turn out like a very interesting adult. I think. So you turn out like a weird kind of strung out alone person as as you get older. So it’s just figuring out like, how do you properly enjoy your youth while still making sure that you’re putting in the time to enjoy your older and middle age? Which is a more, at least from what I’ve seen from other people, the way to enjoy being an adult is to set up like a safe, sound, loving relationships, a positive relationship to your work that’s incorporated into your life in a healthy way. It’s like doing all this small building. So it’s like, how do I get enough joy out of my twenties while still be doing enough prep for the small building to get joy out of my thirties and forties and fifties and sixties.

JB: What does “MOSS” mean?

MH: It came later. And I think it isn’t a lyric in any of the songs of this record. It weirdly is a lyric in one of my songs from my first record, “A River Like You.” But I was trying to come up with the title for the record, and I was walking through the woods in the back of my mom’s upstate house that’s kind of home to me. There was all of this moss growing over these stones, and I’d always had kind of a like a back of my mind, curiosity about the expression, “a rolling stone gathers no moss,” Like moss is so beautiful. So do you want to gather moss? But also the idea of being a rolling stone was always so romanticized. Like a lone wolf. A rolling stone moving and shaking. And and in the pandemic, which is like this is kind of a pandemic record, we all had to be still and not be rolling stones anymore and gather a lot, quite a bit of moss.

MH: I thought that this record was kind of like the moss that I gathered when I stopped being a rolling stone. And that’s why it’s called “Moss.”

JB: What is a song that you can’t stop listening to right now that’s not yours?

MH: I have a great answer. I have some friends who all have separate music projects, but came together to be in this band called Peach Fuzz. And they just put out a song called “Shaking the Can” and I cannot stop listening to it. I think it’s like one of the greatest songs ever. It’s like a perfect song. I’m obsessed.

JB: Can you tell us why it’s a perfect song?

MH: I don’t know. It’s hard to say because I even hate the word perfect. But I guess for me it has an amazing combination of, like, uplifting energy where, like, I want to listen to it when I’m walking down the street and, like, boogie to it by myself and all, like all those things. But also the lyrics make me think at the same time and make me have feelings that are complicated and not straightforward. And a song that can do both those things like make you have not straightforward emotions and make you want to get up and dance is a perfect song to me.

JB: Who’s your favorite songwriter ever?

MH: Or, like, living and working or.

JB: Let’s say ever.

MH: Such a hard question. It changes all the time. I mean, like and it also changes if it’s like you’re talking musically or lyrically

JB: Lyrically.

MH: Probably Leonard Cohen. It’s just, like, brave poetry. I mean, John Lennon, Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen. I don’t know. I was going back and I was listening to them the John Lennon, the Plastic Ono Band record on the plane the other day. And it just like, my access point into songs is poetry. So and I would never tell anyone else that that should be theirs. It just happens to be mine. And listening to the way that so much storytelling is happening and the emotional performance that is interconnected with the language it feels like of John Lennon. He always feels like there’s I don’t know, it’s like a a theatrical level of connectivity there. And that always really spoke to me.

JB: And I think that that is why, like I am connected to music and music. Leonard Cohen’s like my number one. Yeah. And I think that that’s why I am connected to your music because there are people that are singers first. There are people that are musicians first and there are people that are poets first. When I listen to you, I’m like, this is this is coming from a place of thinking about the poetry first.

MH: For me, that’s for sure true. I feel like, I hope this just doesn’t come off badly. But there’s no place in capitalism for poets. Even calling yourself a poet has like some weird ring to it. It’s a tough word. I think that in songwriting and even in acting, in storytelling, in all those things, you can find places for poets.

MH: I also love his separate, just written poetry. I don’t know if you read, you know, his poem, “How to Speak Poetry.”

JB: No.

MH: It’s an unbelievably amazing poem. It’s really long. And I like a remember it’s very I memorized it at a certain point in my life and it’s it’s really, really smart about language. And it’s impacted me as an actor and as a writer in like ten ways to Sunday.

JB: Can you give me a couple of bars that you remember?

MH: Yeah.

MH: Take the word butterfly. To use this word, you do not have to make your voice way less than an ounce. You don’t have to equip it with small, dusty wings or imagine a field of butterflies. The word butterfly is not a real butterfly.

MH: That’s how it starts.

JB: That’s great. Okay, that’s it.