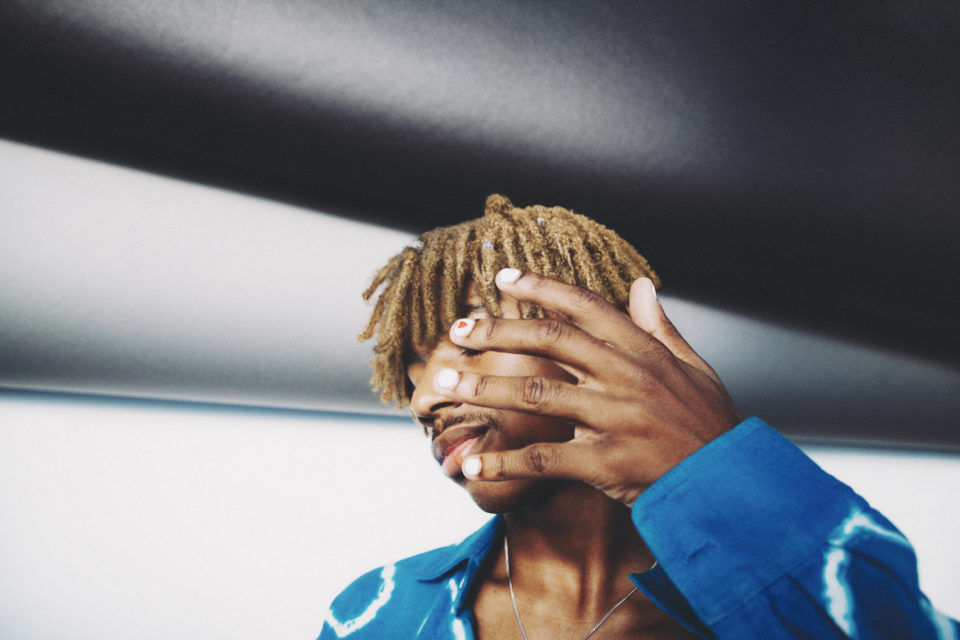

To hear midwxst describe his musical evolution is to encounter a dizzyingly compressed concept of time. Between his high school years in Indiana, a short stint studying at Belmont during the pandemic and the lead up to his new EP better luck next time., the singer, rapper and songwriter born Edgar Sarratt III metabolized the affecting, detailed narration of artists he considers elders, like J. Cole, Frank Ocean and Tyler, the Creator, and also took in what SoundCloud rappers and hyperpop and digicore upstarts closer to his age were creating and sharing at the speed of the internet. In no time at all, midwxst found collaborators and community on the chat app Discord, and fashioned the elements he felt were the most potent and eruptive into his own expressive style.

Preferring to channel the immersive intensity of a moment as he’s living it, he hops on the hyperactive beats, heavily distorted electronics and pop-punk guitar figures he’s sent by online producer friends, and thinks nothing of vaulting from hip-hop swagger to squalling emo hooks and softer pop-R&B gestures. midwxst’s new tracks, some of which, including “i know you hate me” and “on my mind,” he recorded in his Nashville dorm room, land with the force of youthful catharsis. His visceral, stricken imagery and tonally varied vocals — sullen and slack, stubbornly avoidant, accusatory or anguished — are the communication breakthroughs of a young artist committed to the telling of his own emotional truth, and that’s bracingly powerful stuff.

On the Record: A Q&A with midwxst

Jewly Hight: So is the bedroom I’m looking at the same bedroom where you started making music?

midwxst Yeah. I started making music in my bedroom freshman year of high school. I had these Beats headphones and they had a cable on top with a microphone. I used to rap on it like this [holds headphone cord up to his mouth]. And it was actually pretty fun. I was never really doing anything serious. Then afterwards, I started to invest in an actual studio set-up. I wanted to make that into a bigger reality instead of it just being a joke thing.

I’d always been in love with music. If you look around my room, I have so many musical posters.

JH: I see Frank Ocean behind you.

m: J. Cole right there. [Points to one wall, then another.] You got Juice WRLD. The Weeknd’s right here. Then I got Tyler [the Creator], because those are some of my biggest influences.

JH: I read that some of your earliest attempts at making songs were a little more in line with classic rap of earlier generations, and then you worked toward really finding your own sound. What were you zeroing in on? How were you found finding the sounds that spoke to you?

m: I’d always been in the hyperpop realm and scene, but I’ve always brought the flows of hip-hop and the flows of rap in the way that people will use punch lines and one-liners and bars in hip-hop. I brought that to the table for hyperpop, and I just started to rap on beats that ended up fitting into that genre and everybody started to move them into that genre.

But finding my sound definitely took time. I don’t think I really have a defined song. I end up just making songs because I like the beats ,and I like beats from like every genre ever. I’ve made alternative songs, I’ve made slow R&B songs, I’ve made Lil Durk-ass hip-hop songs. I’ve done all those things, because those are all things I’ve been interested in. And those are all sounds that I know I can do. It’s just a matter of if I can execute it right, because I don’t want to do something and then have it be half-assed or have it be bad. I want to be able to put my best foot forward for whatever sound I go for.

JH: It must have been kind pivotal when you went from digging what you were hearing through your parents to finding things that spoke to you directly, like SoundCloud rap and hyperpop and other things that that you could feel ownership of in a more immediate way, that felt like they were yours as opposed to belonging to artists and fans of a generation ahead of you.

m: The thing that belongs to us is right now — I’m not going to lie— it’s the internet. Because without any social media, without Instagram, without Discord, without Twitter, without any of those things, I wouldn’t be at the point I’m at right now. That’s how I met all of my friends who produce for me now. That’s how I met all of my music friends. That’s all through the internet. It’s really been a tool.

When quarantine happened, when COVID was at its peak, a lot of us went online with that time and we started making songs, started going outside our comfort zones, experimented with stuff that we never had experimented with on the musical side of things and sonically. And it ended up becoming some of the best periods for us as teenagers and as young adults, as a whole, just on the internet. Everybody was so eager to see what everybody was doing, because we were all in the same circumstances, in the same settings, all were inside on our laptops. So it’s like, “How is this person going to make this different from how this person is doing it? Or is this going to be a new sound or is this sound going to fall off?” It opened up a lot of conversations that we weren’t really having beforehand.

JH: How was exploring different sounds and styles connected to what you actually wanted to express, the tone you wanted to strike in your vocal delivery and in your writing with your emotionally charged language and the way you channel the intensity of mental health struggles?

m: The reason I started talking about that was personally, I suffered through a lot of mental bad spots. I was very depressed. I was diagnosed with ADHD before I went to middle school. When I was in middle school, I had to take medication, and it just didn’t make me feel like myself. It made me feel like a whole different person. I felt like I was just driving on autopilot in my own head and my own body. Once I got off of those, it really gave me time to see who I truly was as a person.

And I realized that, to be honest, there’s not a lot of Black artists, especially [in] my age demographic, who are able to talk about being vulnerable and talk about expressing emotions and talk about all the things that you might not expect a kid to talk about. But I do, because I know that there’s people out there who understand, who can relate to what I’m saying, who have been in the same shoes.

You don’t really hear that a lot, especially in the Black community, because a lot of times in Black communities, Black men are brought up in a sense where it’s like, “Oh, you have to be strong, you have to be resilient, you can’t show weakness, you can’t show that you cry. Boys don’t cry.” This very “macho man” attitude to things, when in reality, I think it’s more manly if anybody comes out and talks about things that are that are impacting them in a negative way and speaks out about how they feel, [more] than keeping it in, suppressing it because you want people to see you a certain way, as a tough guy.

I have a really wide audience, but at the end of the day, I make music for kids like me. I make music for kids who have ADHD, who never really fit in at school.

I was in a really, really dark place mentally with education and a lot of things that I didn’t want to express to my parents. I wasn’t able to sit down and talk to my parents and have a normal conversation about how I’ve been feeling emotionally, until they found out about my music. And they heard “Trying” and they heard some of my other songs where I talk about these topics. They never understood that side of me, but hearing that side of me gave me gave them hindsight: “OK, maybe we should check up on our son. Maybe we should ask how he’s doing.” Like, they always had been, but I was just never confident enough to speak up about it and say a word about it.

But then when I started to do music and stuff, it was like, “If I can talk about this stuff in my music, what’s stopping me from having these conversations?” If I kept bottling those things up, I was just going to end up on self-destruct. Nothing good comes from that. To me, music is a form of therapy. It’s a form of ranting. I use this as a way for me to get out how I feel. Like, when I’m angry, I’ll go to the microphone and I’ll start screaming at it and yelling shit and talking my shit. And then afterwards, I’ll see that the anger that was in me, it’s not even there anymore.

JH: You were talking about making music for people who share your experience, people who are your peers. How could you first tell when the tracks you were putting out were connecting?

m: I think the first instance was when I dropped “Trying.” There were bits and pieces of the lyrics in there that were from the suicide note that I’d written. So it was a really heavy song for me at that time, but I got a DM from a kid on Instagram out of the blue. And it was his whole biography on himself and where he was from, how he was suffering with the same stuff. He told me his whole life story.

I think that moment, for me, was just a full circle moment, because it made me realize, “Whoa, I’m not just making music and putting it out. I have an audience and I have people who can resonate with what I’m saying.” Look, I’ve had a lot of people text me and talk about how “I Know You Hate Me,” it’s like a perfect example of a love-hate relationship and toxicity in relationships and standards that society puts on relationships, all these things that people can relate to it because they’ve been in the same shoes before. It made me happy, made me smile, like, I was cheesin’, because I never expected to have this impact on people. But now that I have it, I’m going to use it to talk about this stuff I understand that needs to be talked about.

JH: What kind of path were you envisioning from there when you started getting viral success and went from being managed by your mom to growing your team, signing with a major label and deciding to go to Belmont and study audio engineering for a little bit?

m: To be honest, the music stuff was starting to become a priority, but at the same time, I was a kid first, I was a student first, I was a teenager first. I wanted to experience all the things that my peers were experiencing. I was going out with my friends. I was going to parties, all this stuff that you’d expect high school students to do. I wanted to experience that. Just because I was starting to get a little bit internet famous doesn’t mean that I’m the next big thing, so I wasn’t getting my hopes too up. I didn’t want to lose my normality. I didn’t want to jump into the spotlight when I wasn’t ready for it. I wanted to wait for that moment to come.

But then when it was constantly back-to-back articles and recommendations and reaction and people loving my music and all those things, I was like, “OK, maybe I could do this full time.”

I didn’t have to go to college, but I still wanted to. I really, really had my mind set on college. I want to go back and I want to finish. It’s just that right now, so many things are happening.

JH: Well, how did how did it work out when you did go to college for that year?

m: Oh my God. It was congested. It was busy. I finished with all A’s and B’s on the semester, so I was super happy with that. But on the weekends, me and the homies would go out to these house shows in Nashville, in somebody’s basement or somebody’s living room or something like that. And you’d watch and you listen. And I went to a bunch of those and just being in Nashville exposed me to a bunch of things.

JH: How much of this new EP did you make during that time? And what did that one of that actually look like?

m: “i know you hate me” I made in my college dorm. I made “Bluffing” in my college dorm. And then I made the outro to my EP “in my mind” in my dorm room too.

So here’s what it looked like: So I have my bed right here, my little bunk bed. My bed was on top underneath. I had a desk. I had my monitor. I had my PC under the desk. Then I had my microphone right here, like how it is right now.

There is such a cool story for “i know you hate me,” because my friend Tucker, who went to school with me, we were just chopping it up when he said, “I want to show you some stuff I’ve been working on.” He did the guitar loop and the guitar riff. I was like, “Oh my god. I love this. Where’d you get this?” Like, “Oh, my friend found it.” And then afterwards, like, he showed me that he found it on Splice. So I call up [producer] elxnce. I’m like, “Yo, you got to use this loop”. I made that song same the day.

My little friend group in college, we all were musicians or somehow were involved in the music industry. They were all musicians, all songwriters, all producers, all play guitar. It was a group of creatives. And so we all would just bounce everything off of each other. College was such a great place for me, because I was surrounded by people who thought the same way I did.

I showed them “Bluffing” first, and then I had them all sing this part on the outro of the song “on my mind.” I wanted to make it really grand. I’d added hella reverb. I was like, “How can I make this song even fuller? And what could I add to this song to make it sound even more complete? A choir would sound really good on this.” And I was like, “OK, I don’t want to pay for a choir, so I’m going to make my own choir.” And so then I called up all my friends, like, “Hey, can you come to my dorm? I’ll check you in. I need your help on something.” One by one, they started coming to the door and all of them were very, very vital in the creative process for this song.

In “on my mind,” you can hear the emotion behind the sustaining “ahhh,” before it goes into the hook. You can hear the emotion in that. You can hear the emotion in all these songs in the EP, because that’s what I actually felt. That was me being a hundred percent vulnerable at that time period. I didn’t hold anything back in that song. And that’s why I think it’s such a good song because it’s just unfiltered, raw emotion.

JH: Let’s take a step even further back, because you’re talking about the skill that you have developed to tell a story about what it’s really like to live in a moment. When did you figure out how to do that?

m: I think it was when I did poetry. I wrote poems and I did spoken word and open mikes for my freshman year and sophomore year of high school, because of my English teacher, Miss Horton. She was a poet herself, and her class was really in the moment. Like, if somebody was having a bad day, she would stop the class and ask everybody how their day’s going. She’s one of my role models and one of the main reasons why I even got into storytelling.

My first poem was one about a Black person getting stopped at a light, getting pulled over by the police, and creating those scenarios where I can say something and then a visualization can pop up in your head and you can imagine that. That’s really where I got that skill from, along with studying, looking at deconstructed videos of A Tribe Called Quest and how they deconstructed “Bonita Applebaum.”

There’s one common thing with old hip-hop: they’re all storytelling songs. I was really inspired to do that. That’s why I like J. Cole so much. That’s why I like Tyler [the Creator] so much. They’re all packaged and put the bow on top. If you go back to the discography, for example, “Neighbors” by J. Cole talking about how his neighbors thought he was running a drug house. And Blonde [by Frank Ocean] it’s talking about masculinity and gender norms in a bunch of things that a lot of people weren’t prepared for in. And Flower Boy, it’s Tyler blossoming. It’s him going outside of his comfort zone. It’s him maturing from that Odd Future era. Those are all stories. And being able to do that is a key thing that I want to learn, and I think I’m starting to get the hang of it.